Inequality, mobility, and the American Dream

With the launch of our new website, we are reintroducing visitors to our policy issue areas. Informed by the academic research we fund, these issue areas are critical to our mission of advancing evidence-based ideas that promote strong, stable, and broad-based economic growth. Through the rest of June and early July, our expert staff are publishing posts on our Value Added blog about each of these issue areas, describing the work we do and the issues we seek to address. The following post is about Economic Mobility.

Intergenerational mobility is at the heart of the American Dream. An economist’s definition of “intergenerational mobility” is the correlation or association between a parent and a child’s income. Most people probably don’t think of mobility in such technical terms but rather in terms of the chances that, with hard work, children can do better than their parents. Put in those terms, intergenerational mobility is about opportunity. The United States is supposed to be a place where everyone has the opportunity to make a good life for themselves regardless of the luck and circumstances of their birth. And in turn, this faith in equality of opportunity implies that today’s record-high levels of economic inequality aren’t concerning.

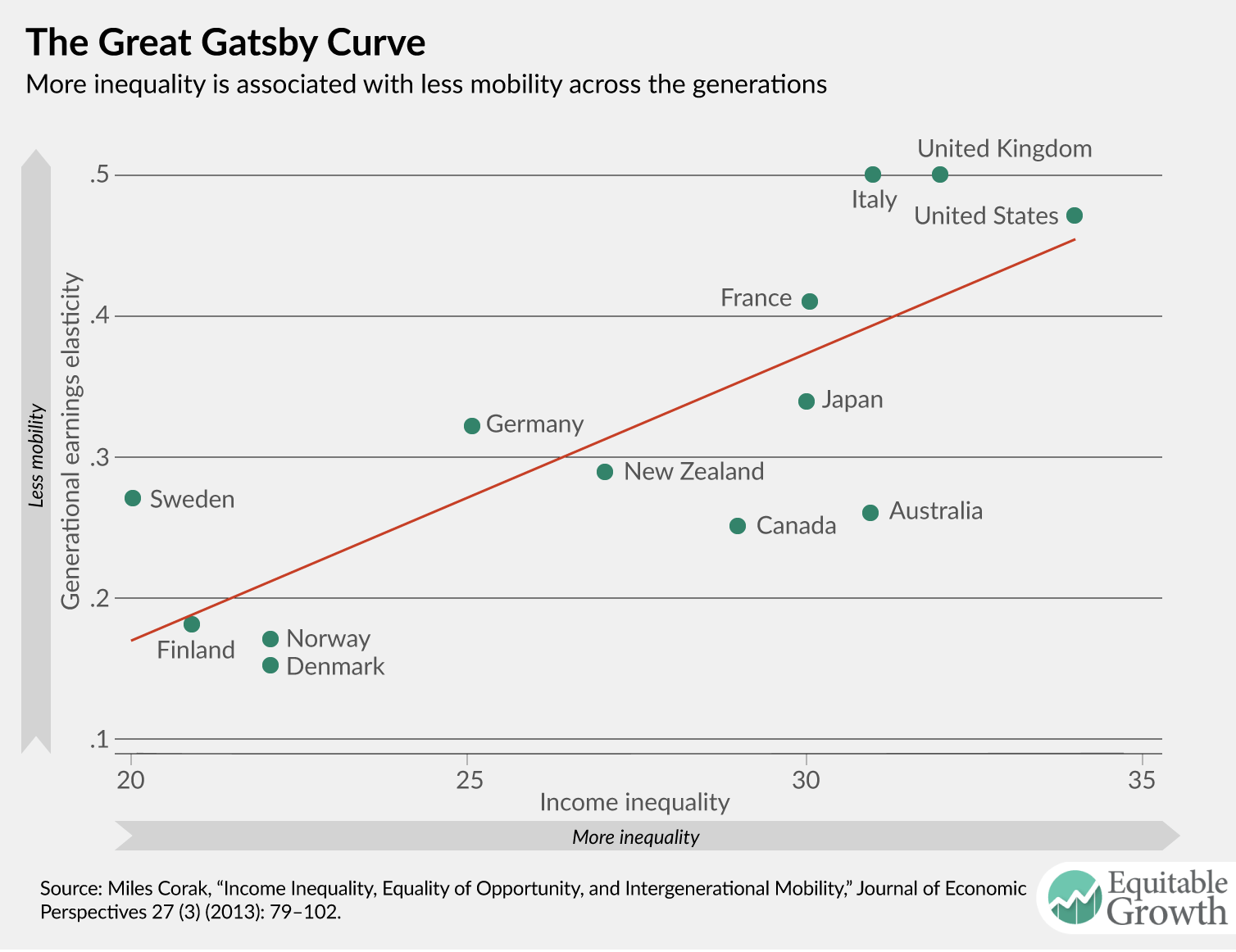

But does research back up this faith in mobility, or is equality of opportunity for the next generation in fact being impeded by today’s inequalities? Well, as so often is the case with economics research, the answer is “it depends.” As City University of New York economist Miles Corak points out, looking across developed countries, there’s an inverse relationship between income inequality and mobility. That is, countries with high income inequality tend to have low mobility. This relationship was dubbed “the Great Gatsby Curve” by former Council of Economic Advisors Chair Alan Krueger. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

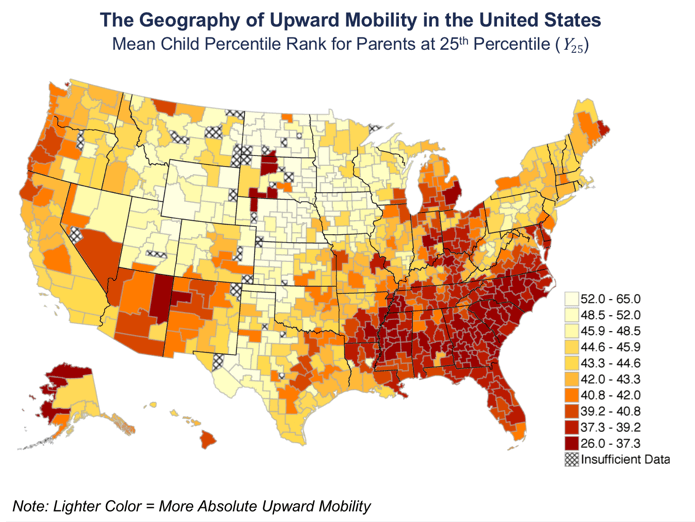

In addition to the variation in mobility across developed countries, there’s also dramatic variation in mobility within the United States, as research by Stanford University economist and Equitable Growth Steering Committee member Raj Chetty demonstrates. This variation is large, as the map below shows, with mobility particularly low in some regions of the country such as the Southeast. Mobility in some cities such as Salt Lake City, UT, and San Jose, CA, is comparable to that in countries with the highest rates of mobility such as Demark. Yet other cities such as Milwaukee, WI, and Atlanta, GA, have lower rates of mobility than any developed country. Similar to the Great Gatsby Curve, Chetty and his co-authors find that greater income inequality is correlated with low mobility in the United States, which is also correlated with more segregation, lower school quality, lower social capital, and more single-parent headed households. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

But these relationships between income inequality and mobility both across countries and within the United States are merely correlations—they don’t show that high inequality causes low mobility. But the differences in mobility in different places hint at where researchers should be looking to explore what the potential drivers of low mobility are. For instance, comparisons across countries find the relationship between a parent and child’s income is particularly “sticky” at the top and bottom of the income spectrum in the United States compared to other countries. This suggests that one of the causes of the United States’ overall low mobility is that kids born to parents at the bottom of the income distribution get stuck there—pointing to the importance of considering the relative impact of poverty rather than just income inequality to improve mobility.

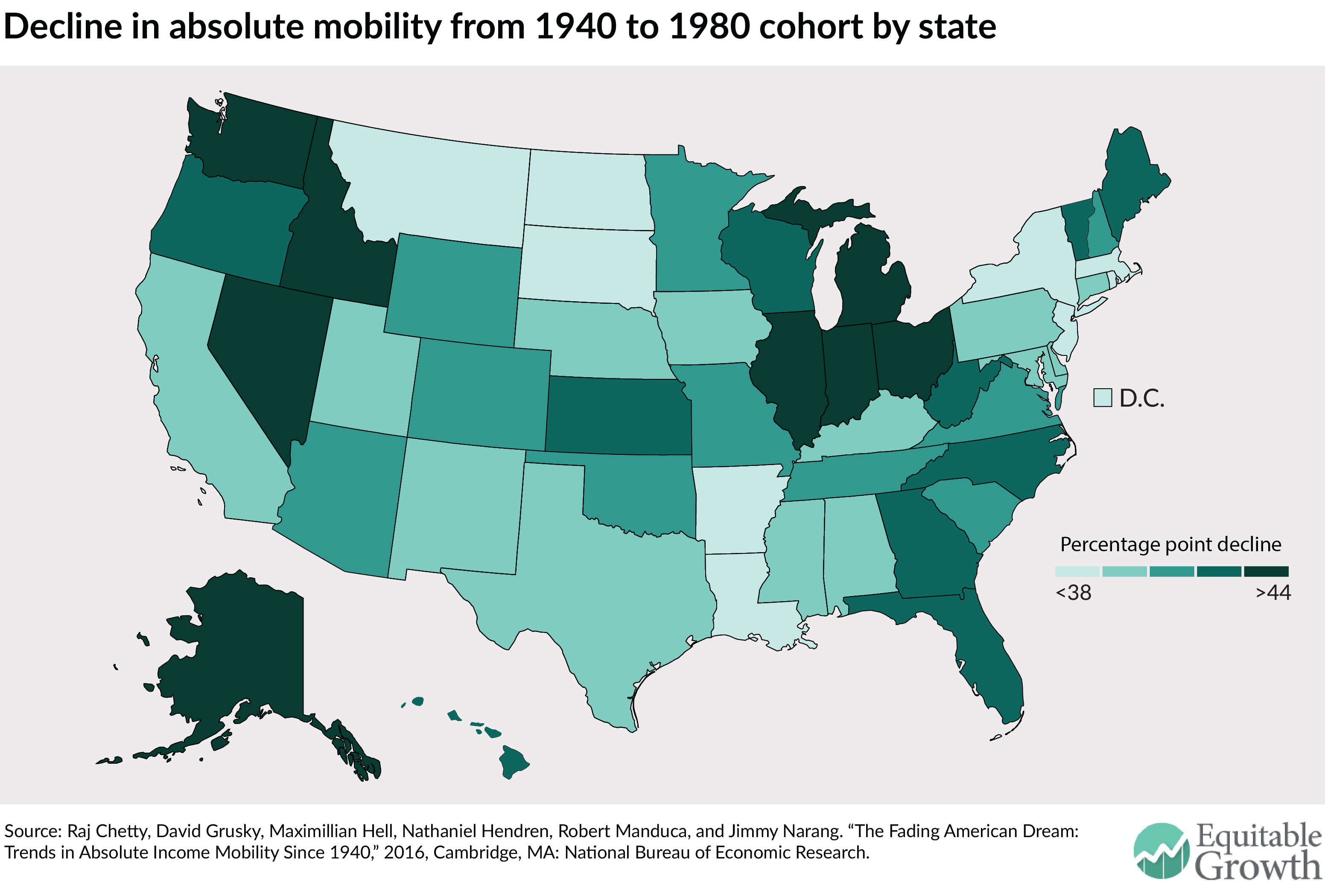

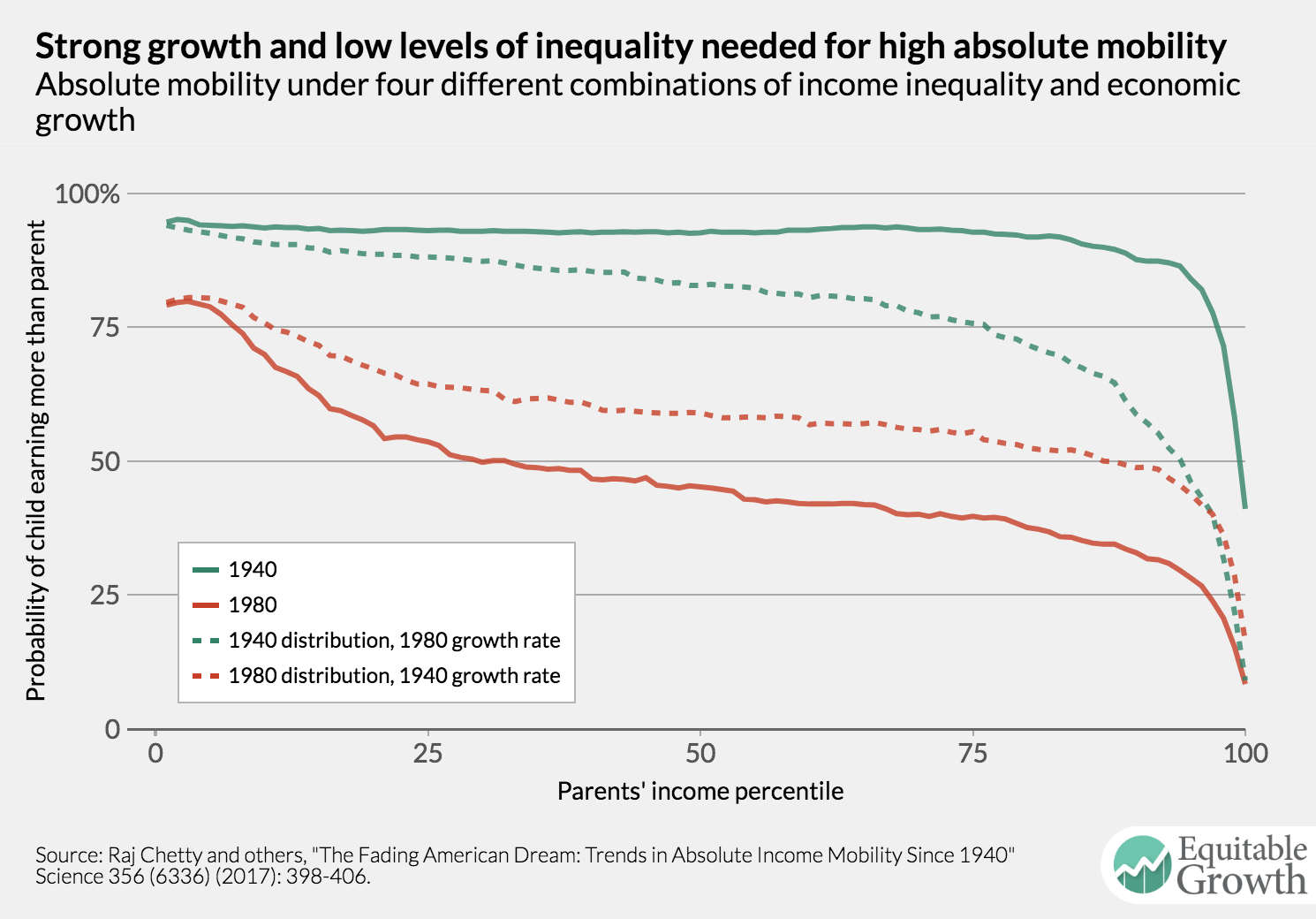

In addition, recent research into the relationship between inequality and mobility finds not only that mobility in the United States has declined since 1940, but also that income inequality plays a large role in explaining why. Chetty and his co-authors find that 92 percent of children born in 1940 earned more than their parents as adults, but that only 50 percent of children born in 1980 out-earned their parents. Furthermore, they find that greater economic growth would close only 29 percent of this gap between generations. But if economic growth was more broadly shared, then more than 70 percent of that gap would be erased. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

Both low mobility and the decline in mobility are threats to the American Dream, as well as to stronger and more stable economic growth. A tight relationship between your parents’ income and your own looks more like the aristocracies of yore than a modern 21st century economy. It also risks leaving productivity and innovation on the table. If your ability to bring your full suite of talent and creativity is impeded by forces beyond your control—your birth weight, what neighborhood you grow up in, the color of your skin—then the U.S. economy isn’t efficiently matching skills with jobs, depressing economic growth. Equitable Growth is eager to see where research into the channels through which economic inequality could be intermediating mobility—and therefore growth—takes our understanding of the American Dream.