How U.S. workers’ just-in-time schedules perpetuate racial and ethnic inequality

In an attempt to minimize labor costs, employers in today’s U.S. economy saddle workers with last-minute and low-quality schedules. These schedules, sometimes referred to as “just-in-time schedules,” are unpredictable, unstable, and often provide workers with an insufficient number of hours. Today, sociologists Kristen Harknett at the University of California, San Francisco and Daniel Schneider at the University of California, Berkeley released new analyses drawing from surveys with 30,000 retail and food workers at 120 of the largest retail and food service companies in the United States to show who suffers from these schedules, and how.

Download FileHow U.S. workers’ just-in-time schedules perpetuate racial and ethnic inequality

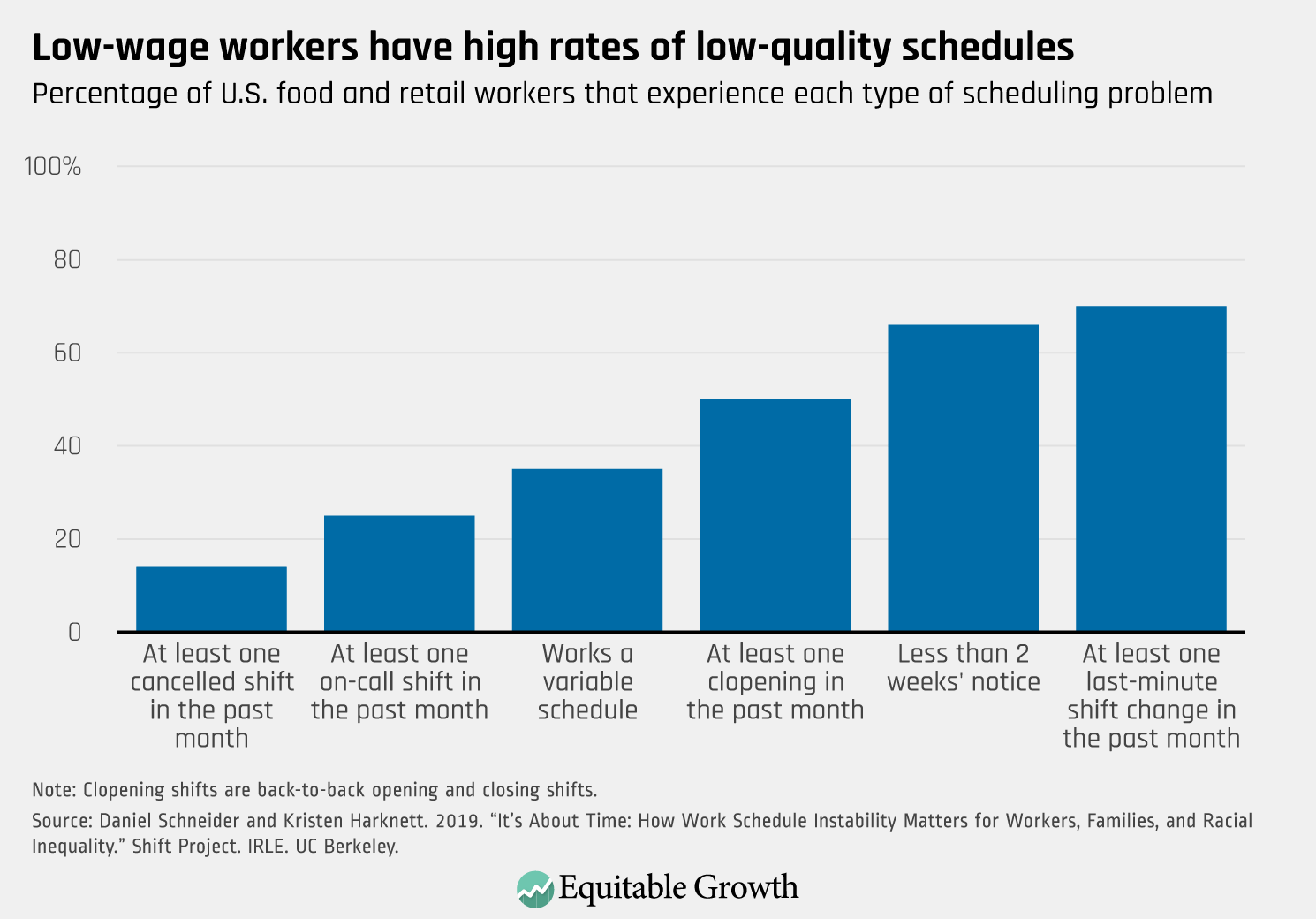

Figure 1

Bad schedules, sometimes referred to as “just-in-time schedules,” are common for low-wage workers: Nearly 3 in 4 workers experience last-minute shift changes, two-thirds have less than 2 weeks’ notice of their schedules, and many face back-to-back closing and opening shifts, or “clopening” shifts, and on-call shifts.

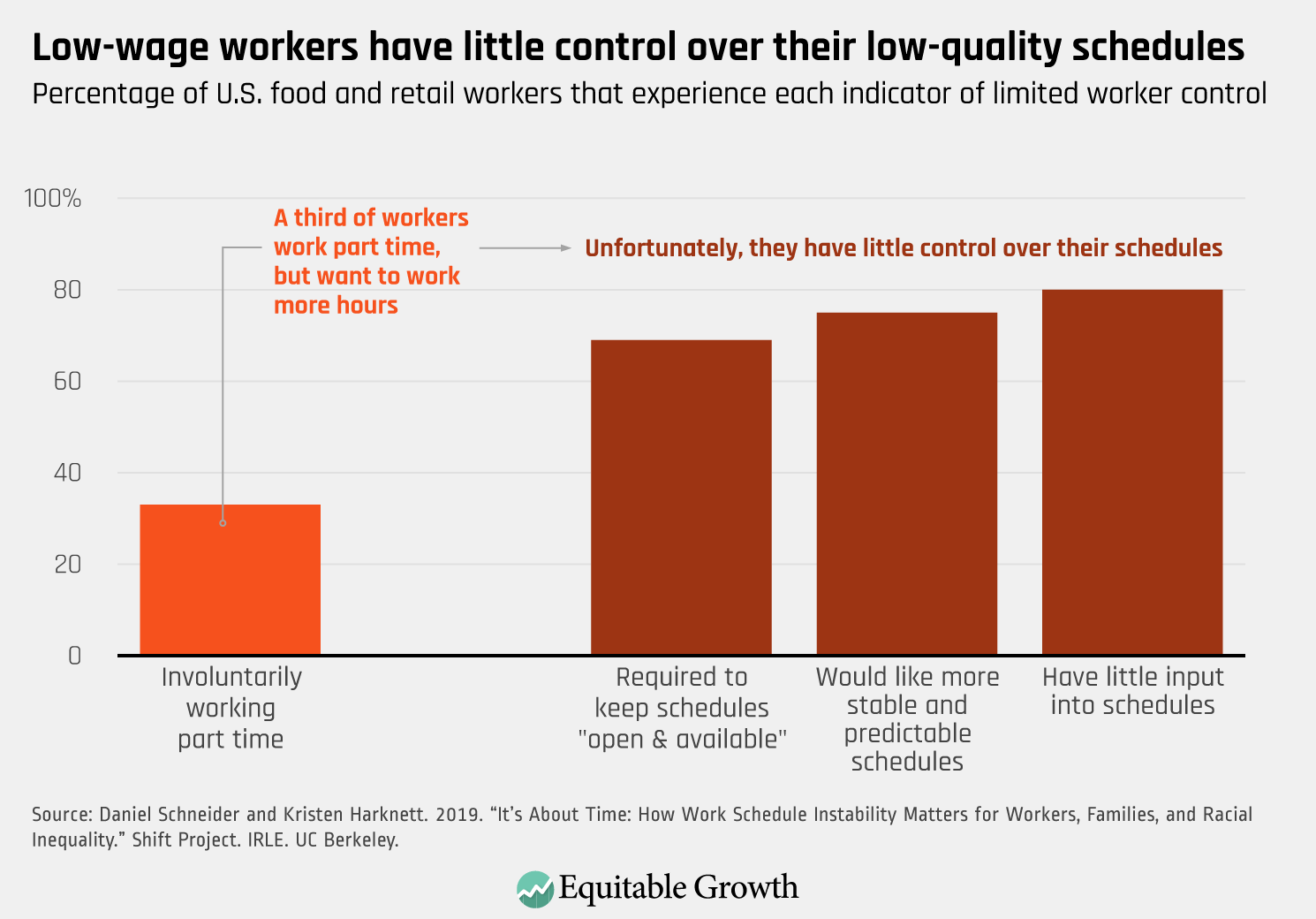

Figure 2

Employers often talk about these practices as being “flexible,” which implies that schedules bend to the needs of workers. In reality, workers have little control over their schedules.

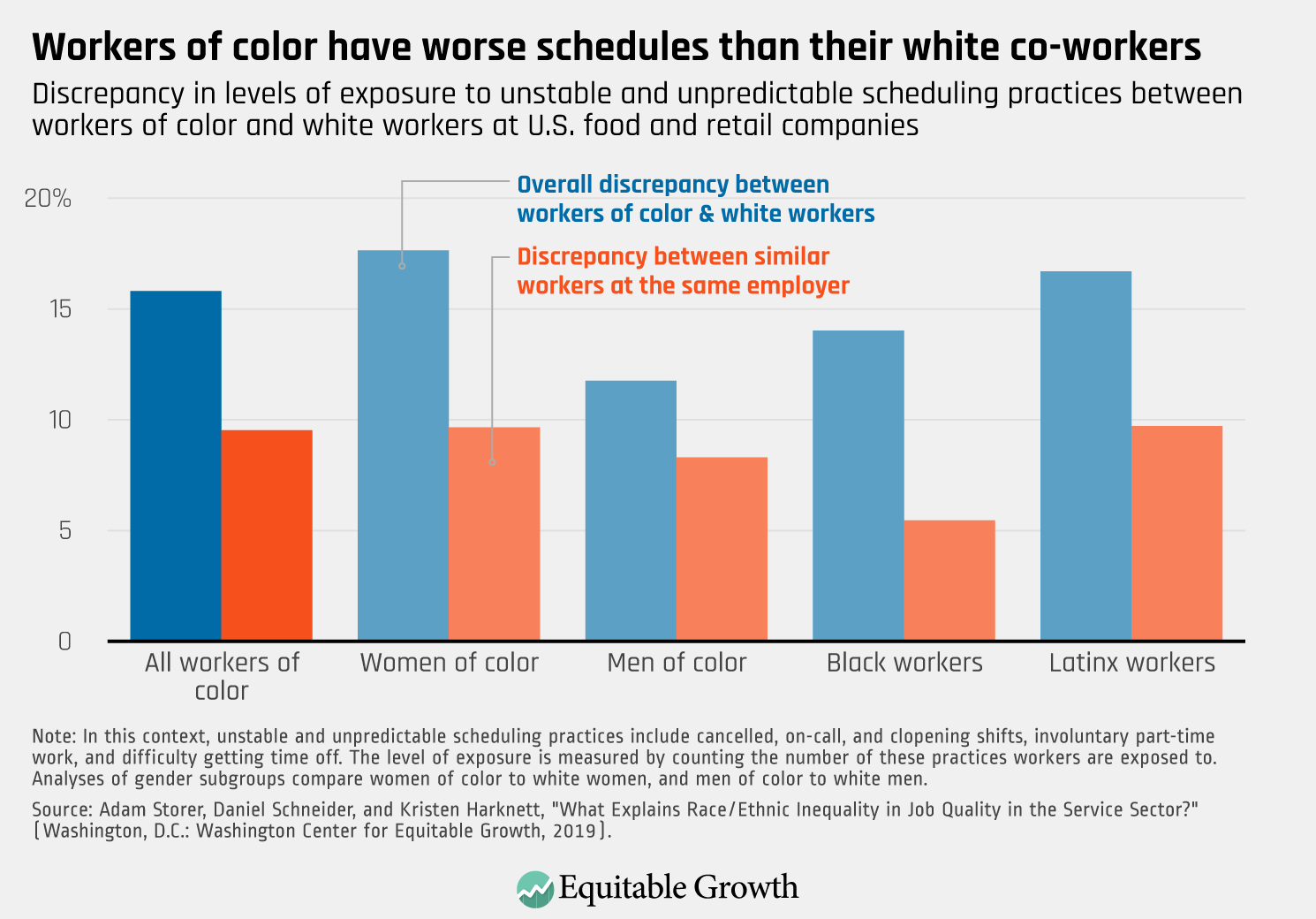

Figure 3

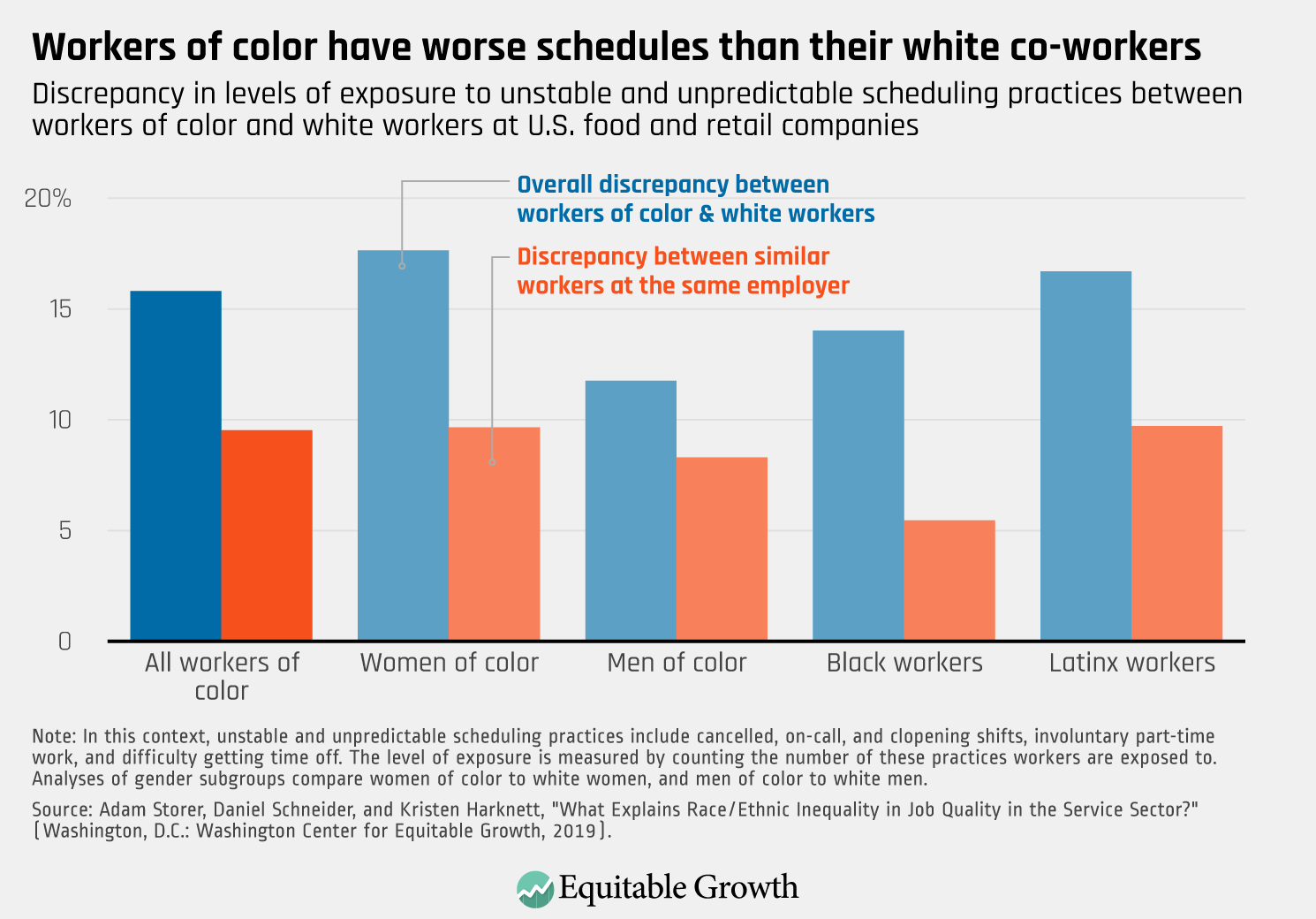

Bad schedules are prevalent, but they’re not distributed equally across the population. Workers of color experience more schedule instability than white workers, and the disparity is largest for women of color and Latinx workers. The disparity remains even when looking at similar workers employed by the same companies.

Figure 4

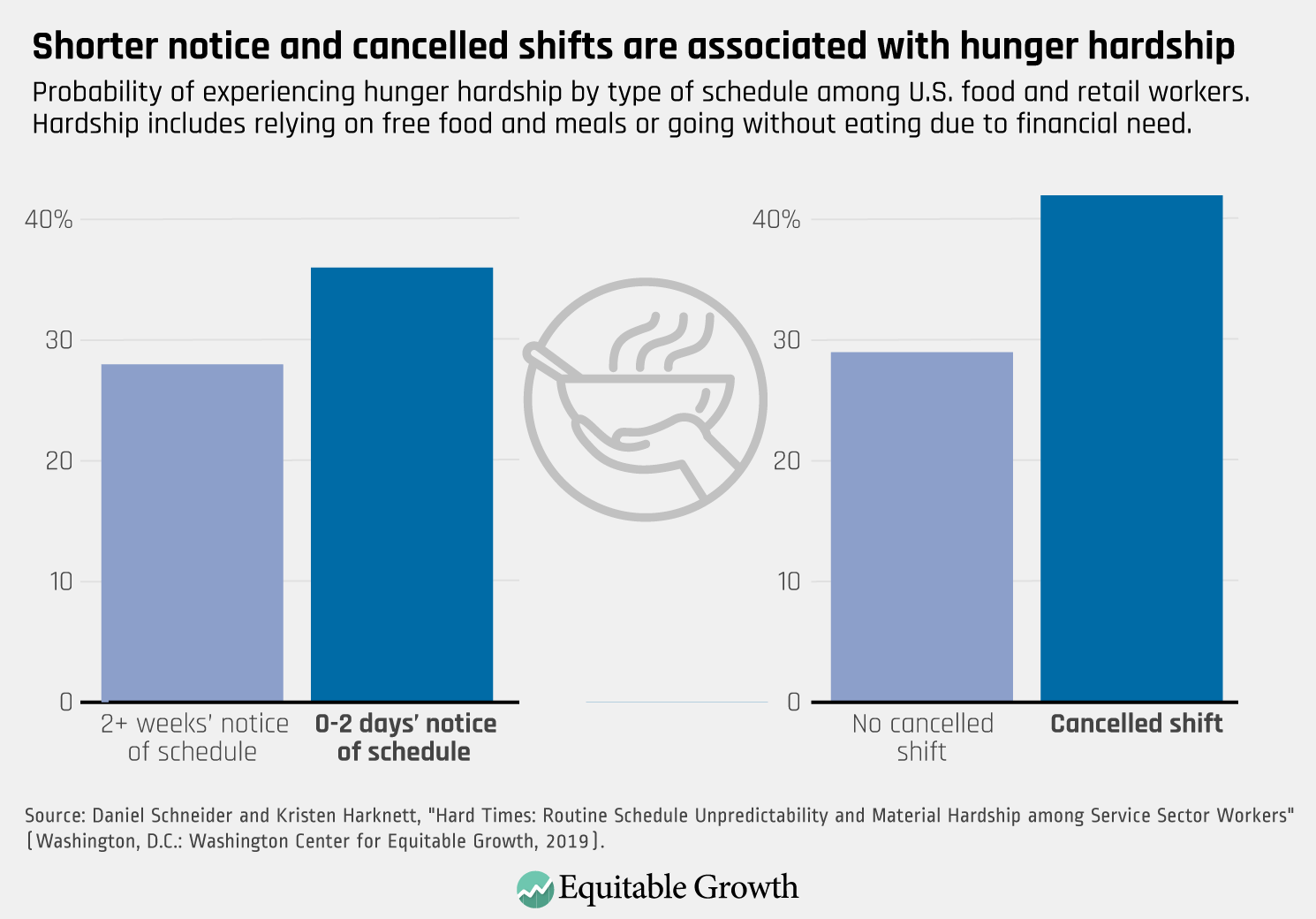

When hours fluctuate unpredictably, it is hard for workers to budget for necessities. Workers with just-in-time schedules are more likely to skip meals or rely on food pantries.

Figure 5

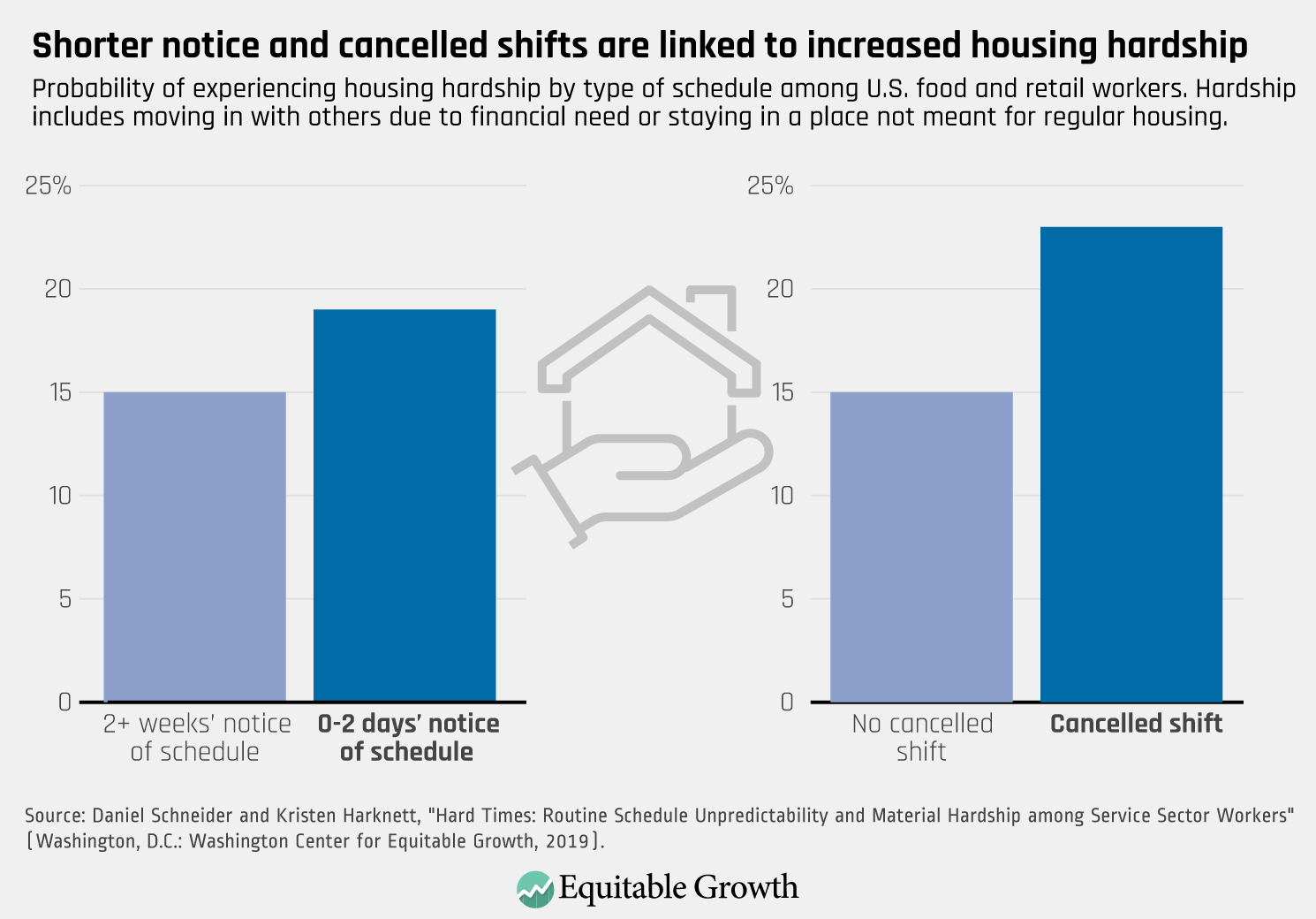

They are also more likely to find themselves moving in with other people to save money, or staying in shelters, cars, or abandoned buildings.

Figure 6

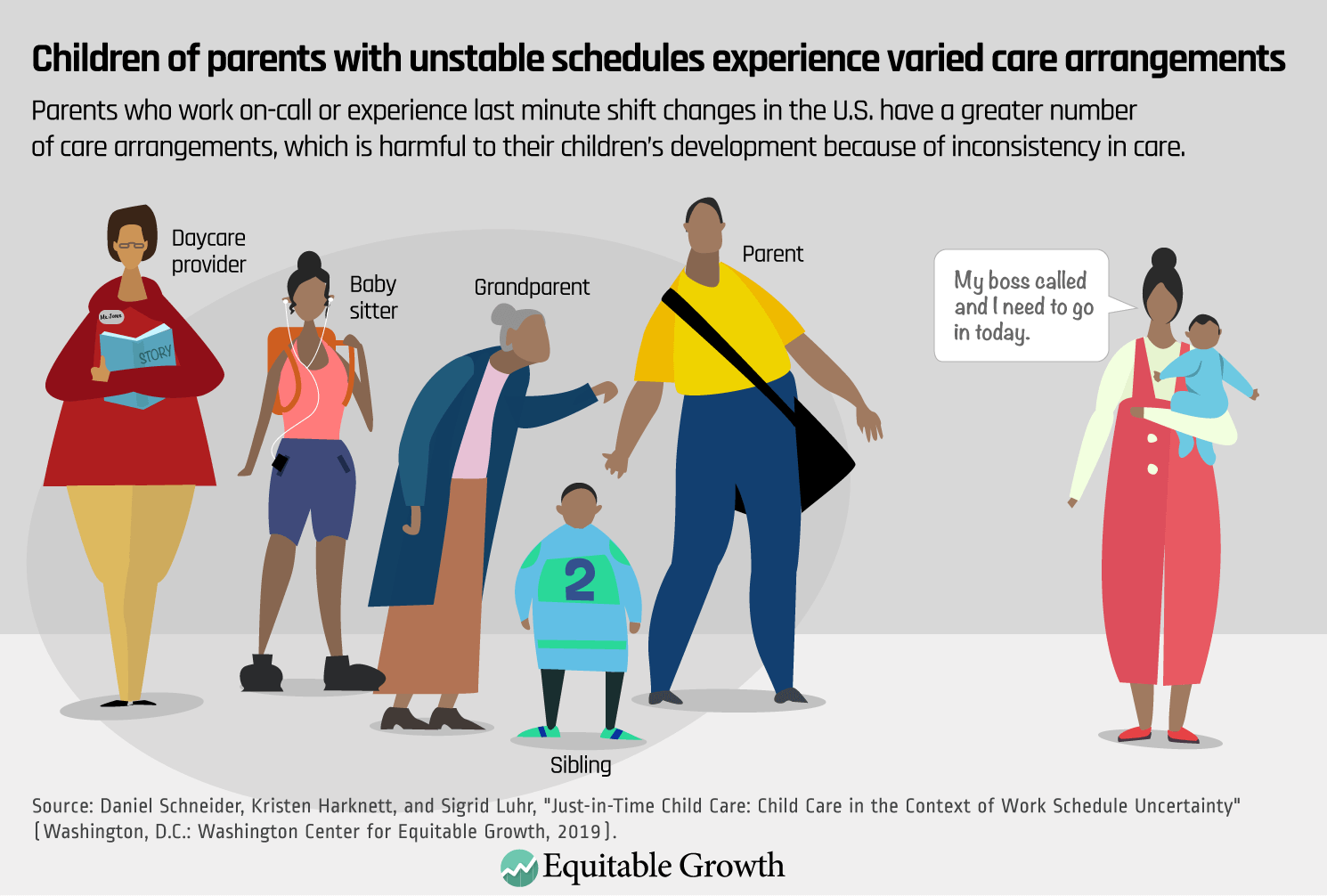

The problems posed by unstable and unpredictable work schedules ripple to the next generation. Parents with just-in-time schedules are more likely to rely on a patchwork of childcare providers, which can undermine childrens’ relationships to caregivers and increase stress, especially for very young children.

Figure 7

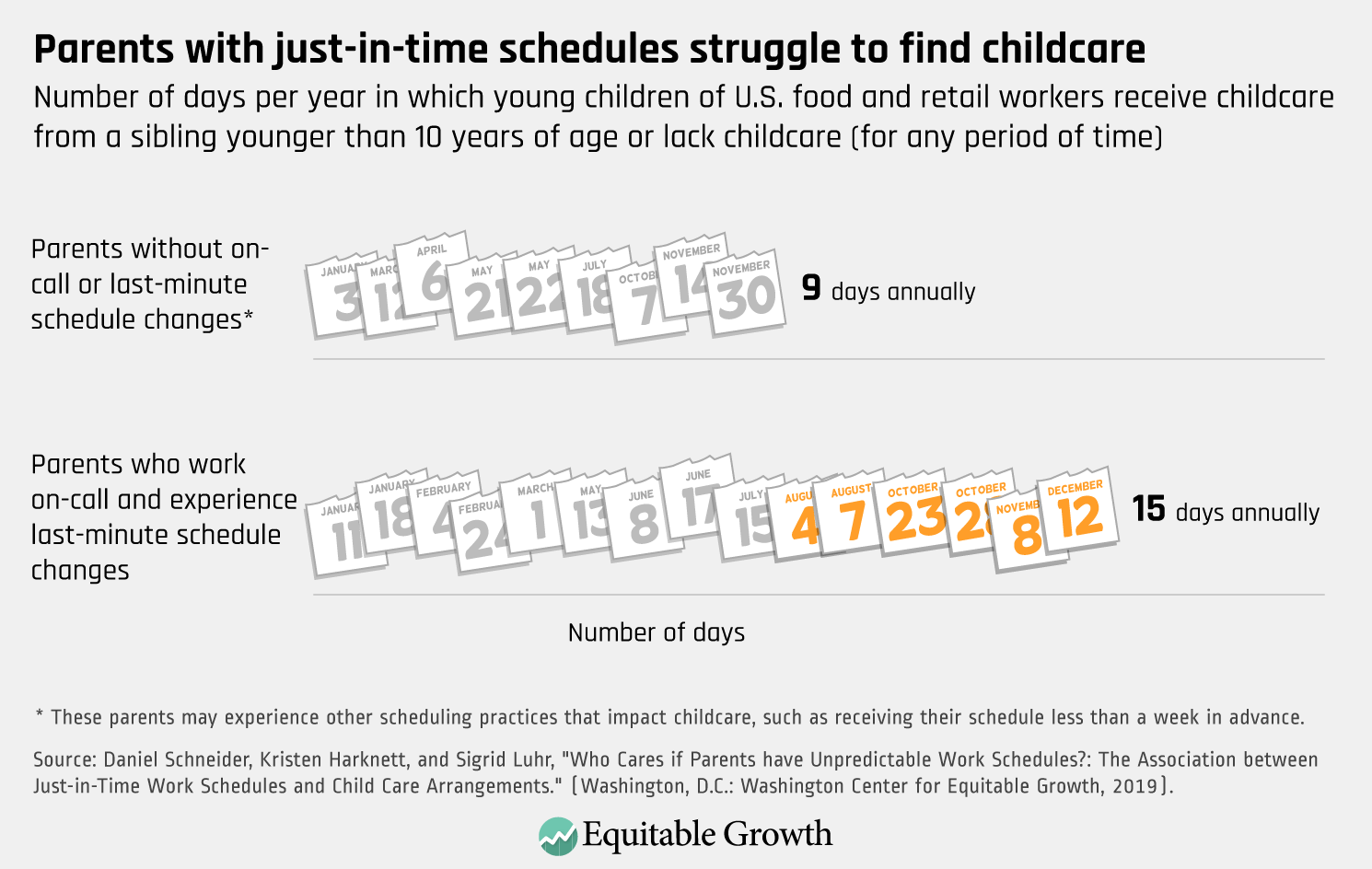

They also struggle to find satisfactory childcare at all: Their children experience moments in which they are cared for by a young sibling or have no childcare six more times per year than workers with better schedules.

Figure 8

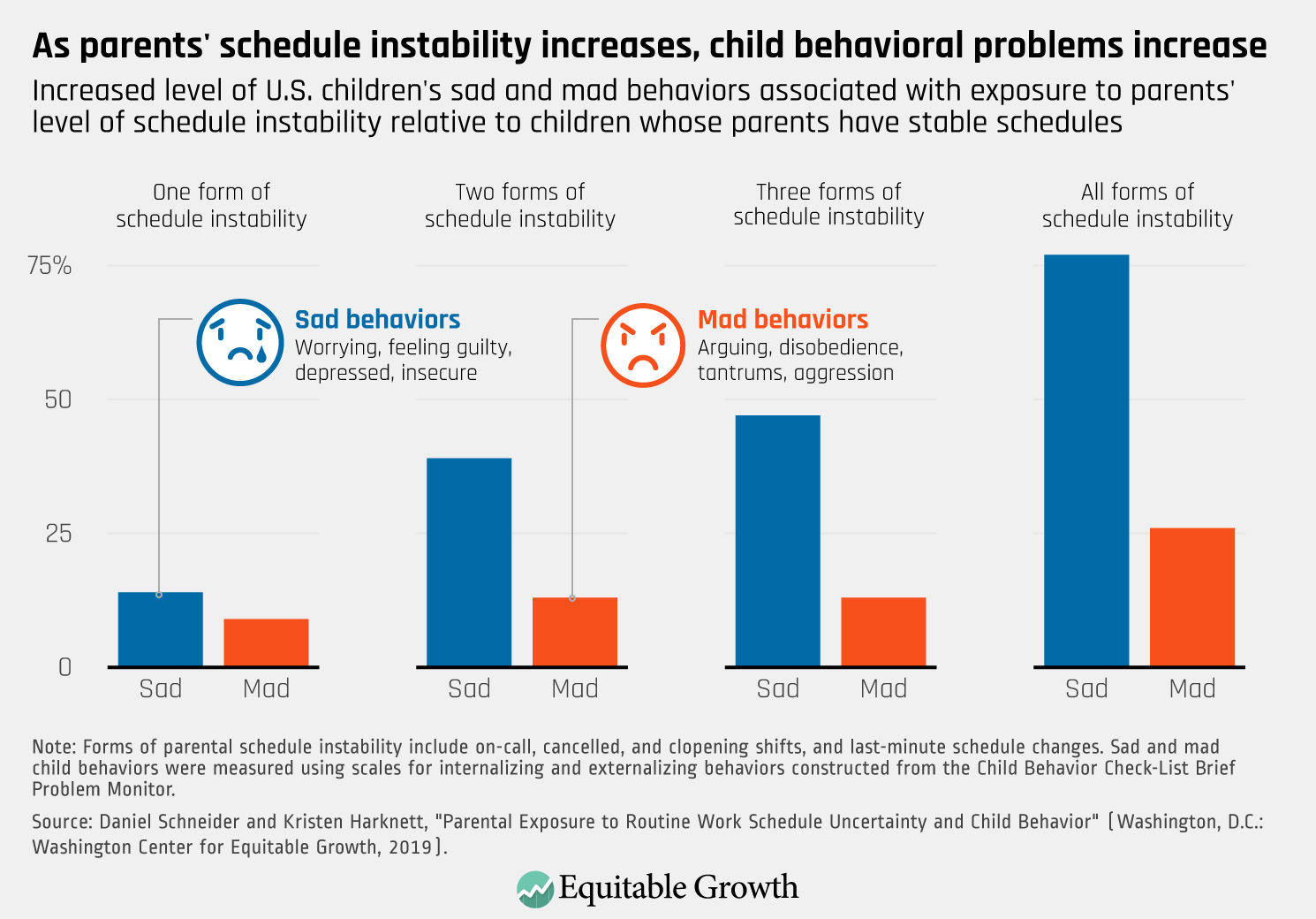

Children suffer in ways that extend beyond childcare. Parental instability is linked to child behavioral problems such as worrying and arguing. The more schedule instability the parent experiences, the more common behavioral problems are.

Figure 9

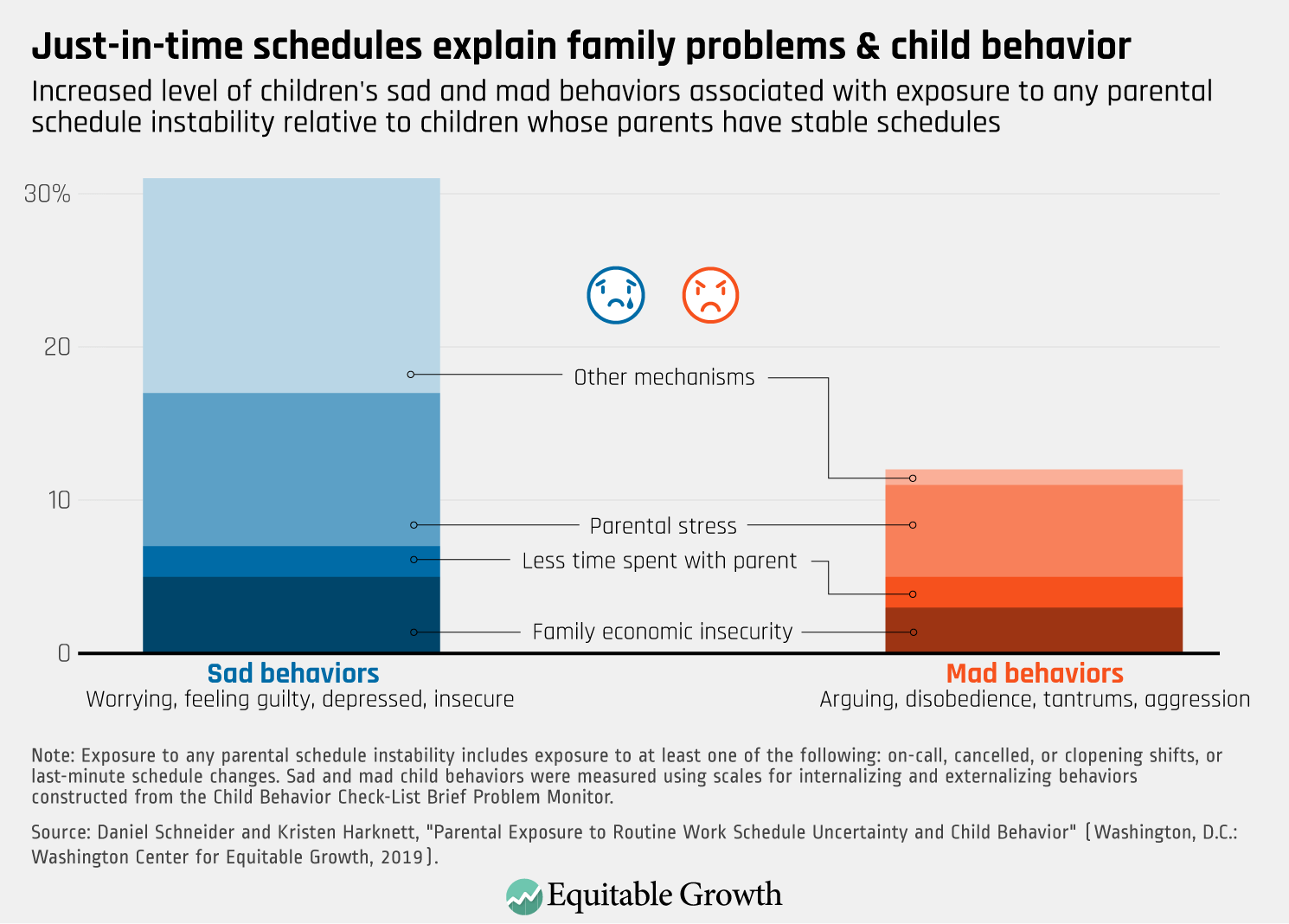

When you think about it, the connection between parents’ schedule instability and their children’s behavioral problems makes sense. Just-in-time schedules are linked to economic insecurity for the entire household, lack of quality time with parents, and high parental stress. All of these factors affect child behavior.

Note: Chart 9 decomposes association between child behavior problems and a dichotomous variable indicating any scheduling problems. This association is not depicted in Chart 8.

Figure 10

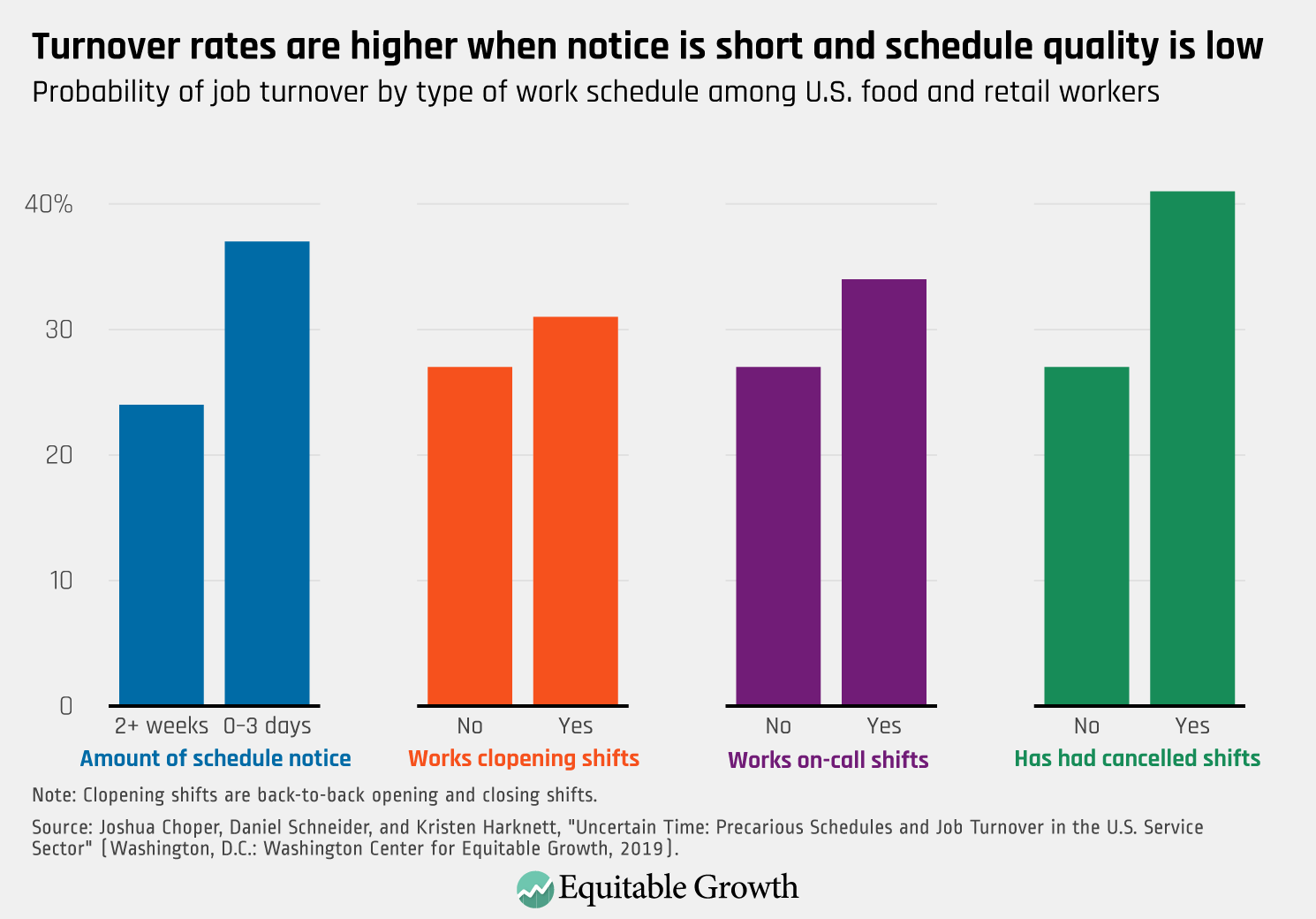

With all these problems, it’s probably not a surprise that workers with low-quality schedules are more likely to leave their jobs.

Yet it’s also important to remember that leaving their jobs doesn’t enable workers to escape the problem—other research shows that turnover is associated with lower wages going forward in a worker’s career.

Back to Figure 3

Again, the negative impacts of just-in-time scheduling are more likely to be felt by workers of color, who have worse schedules than similar white workers employed at their same companies.

That means that workers of color and their families, also disproportionately experience the consequences of just-in-time schedules: hunger and housing hardship, difficulty arranging childcare, child behavioral problems, and job turnover. Just-in-time schedules thus amplify and perpetuate inequality along lines of race and ethnicity.