How U.S. tax policies have fueled right-wing populism

Overview

Among the many factors fueling support for right-wing populism in the United States is federal tax policies. The nation’s tax system confuses, frustrates, and angers many citizens in ways that leave them vulnerable to populist appeals from the right. A mismatch between how the federal tax system works in theory and how it works in practice fuels resentments, playing into the hands of right-wing populists.

In theory, the federal tax system comports with the desire of most nonrich Americans for the rich to pay more. Overall, the system is progressive, taking a larger share of the incomes of high earners. But it has become less progressive over time at the behest of the rich and in ways that complicate the system, especially through extensive tax expenditures—the array of preferential tax breaks in which the government subsidizes some activity by not collecting taxes—which especially advantage the rich. These complications, and the obscuring rhetoric from conservative politicians eager to cut taxes, make it harder for nonrich Americans to see their stakes clearly, fanning both the “right-wing” and “populist” aspects of right-wing populist appeals.

This essay first presents the reasons why the federal income-tax system started out as progressive more than 100 years ago but has become less progressive as wealthy Americans bend the system in their favor. It examines how taxes across the country have become more regressive after factoring in state and local taxes and the aforementioned tax expenditures largely tailored to benefit the wealthy. The essay then details the nub of the problem with taxes and populism, particularly the racially polarizing appeal of right-wing rhetoric about taxes, before presenting some ideas about how to challenge such appeals amid the welter of new regressive tariffs now hitting workers and their families and small business owners.

Progressive taxation: Theory and practice

The story begins in 1913, when the federal income tax was created. Reflecting a desire to harness for the greater good the huge rewards that industrialization had heaped on the small but very privileged group of immensely wealthy Americans, the income tax was based on the ability-to-pay principle: Higher-income groups should pay not just more but progressively more, with tax rates that climb with income. The income tax fairly quickly replaced tariffs and excise taxes on alcohol and tobacco to become the main source of federal revenue, which it remains today,1 built on the idea that those with more income should pay more because they can more easily afford to do so.

The problem is that progressive taxes impose the greatest burdens on the most organized, well-resourced, and vocal individuals in U.S. society. The rich have spent the past 112 years since the creation of the federal income tax working to lower their effective rates of taxation—what they actually pay as a share of income. They have achieved both cuts to marginal tax rates and expansions of the tax expenditure system—the credits, deductions, exclusions, and preferential rates that litter the tax code and that reduce taxes paid by many taxpayers, but especially by the affluent and rich, who gain the most from them.

The rich also have achieved reductions in other progressive taxes, among them capital gains taxes, estate taxes, and corporate taxes. As such, federal taxes are less progressive than they used to be.

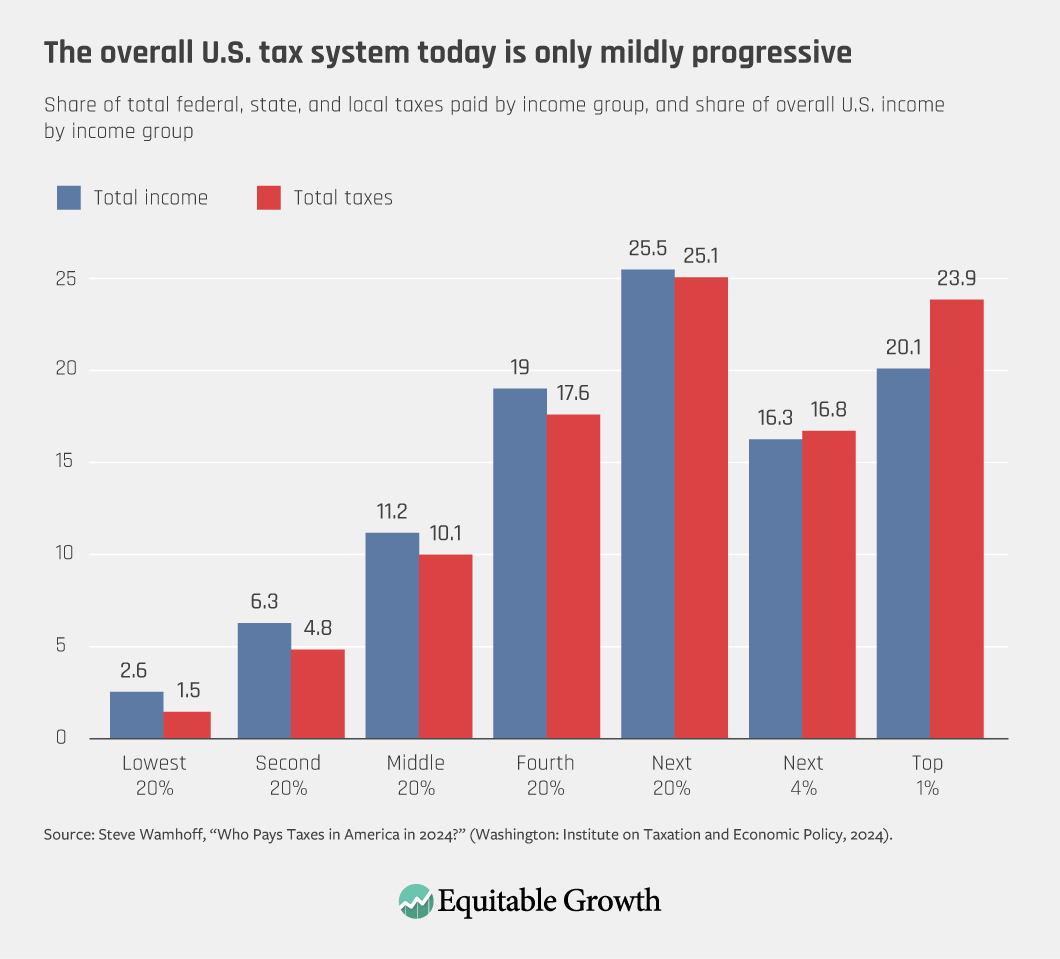

Remember when billionaire investor Warren Buffet said he paid a lower tax rate than his secretary? “Everybody in our office is paying a higher tax rate than Warren,” his secretary added.2 State and local tax systems, which have always been regressive, burdening lower income groups more, also have become even more regressive. Considering local, state, federal, and other taxes together, today’s U.S. tax system is nearly flat, with each income group’s share of total taxes paid about equaling its share of total income.3 (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

How the rich erode progressivity and fuel right-wing populism

The machinations of the rich to blunt tax progressivity have fueled right-wing populism for a variety of interlocking reasons. Consider first the “populism” part of right-wing populism. The majority of nonrich Americans like the idea of progressive taxation.4 They prefer a system in which high-income households pay more—not just absolutely more, but also more as a share of their income. In decades of surveys, from the late 1970s to the present, around three-quarters of Americans say “high-income families pay too little in taxes,” 3 in 5 people say “upper-income people pay too little in federal taxes,” and two-thirds say “people with high incomes should pay a larger share of their income in taxes than those with low incomes.”5

Many Americans are a bit fuzzy about the detailed workings of the tax system, but they believe in the ability-to-pay approach. Next, consider that Americans observe two things about the tax system that go against their own progressive tax principles. One is that when filling out their federal income tax forms, they see the many tax breaks from which they cannot benefit. They have a strong sense that the rich minimize their taxes in technically legal but morally dubious ways, pursuing tax planning and avoidance avenues unavailable to ordinary taxpayers, as Vanessa Williamson, a senior fellow at The Brookings Institution and the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center, found in her in-depth interviews with taxpayers.6 Second, a majority (60 percent) of Americans also know that since 1980, tax rates have fallen for high-income people.7

The tax system is difficult to comprehend, and levels of tax knowledge are pretty low,8 but people know the rich pay less than they used to, violating ordinary taxpayers’ preference for progressivity.9 Periodic revelations in the media that billionaire individuals, such as Warren Buffet, Jeff Bezos, Michael Bloomberg, and George Soros, have paid little to no income tax adds to the populist fury, fueling a keen sense that the little guy gets screwed while the rich can give the tax system the slip.10

Survey data that I collected show that the many complexities of the nation’s revenue system, largely driven by efforts of the rich to minimize their tax obligations, undercut Americans’ ability to put their abstract commitments to progressivity into practice in the voting booth. Americans say they want progressive taxation, but my surveys reveal that the individual taxes they most dislike and want to see decreased are the progressive ones—federal income taxes and the estate tax.11 Meanwhile, the taxes they mind less include regressive sales taxes, which burden them more. For the bottom 60 percent of U.S. households, sales taxes cost more than the federal income tax each year.12

In short, most Americans’ attitudes toward taxes are upside down, given both their abstract principles and their own stakes.

Part of the reason is the design of the tax system. Unless one assiduously saves receipts for an entire year, one never knows the annual toll of the sales tax. Another part of the reason is elite obfuscation. Politicians, especially on the right since the 1980s, rarely discuss sales-tax burdens but regularly lambaste the income tax. Keeping the focus on the income tax and estate tax plays into the hands of the rich, rendering the rest of the public unwitting allies in their long attack on these progressive taxes.

The nonrich are perpetually on board with efforts to cut the reviled income tax, and clever tax policy architects throw them crumbs, such as the $300 rebate checks included in President George W. Bush’s tax cuts in the early 2000s and the new no-tax-on-tips provision in President Donald Trump’s just-enacted One Big Beautiful Bill Act. These tax cuts in this century are tiny compared to the really big cuts for those at the top of the income and wealth ladder.

Or consider that 80 percent of the corporate tax cuts in the 2017 Tax Cut and Jobs Act went to the top 10 percent of the income distribution, with the top 1 percent capturing 24 percent and low-wage workers receiving none of these tax benefits.13 The One Big Beautiful Bill Act makes permanent the 2017 law’s deduction for pass-through companies taxed in the individual tax system rather than the corporate system. That tax break is slanted toward the rich as well, with 91 percent of pass-through income accrued by the top 20 percent of filers, and 57 percent going to the top 1 percent.14

The tax system also fans the ‘right-wing’ part of right-wing populism

Conservative politicians have long invoked racialized rhetoric in their attacks on the tax system, playing up the notion that taxation is illegitimate because the government spending it enables goes to undeserving “others.” President Ronald Reagan famously attracted working-class White voters with messaging that mixed taxes, spending, and race.15 That framing, however, predated President Reagan by more than a century: In the post-Civil War era, conservative politicians ran on anti-tax platforms, telling White southerners they should not have to pay for Black schoolchildren’s educations.16

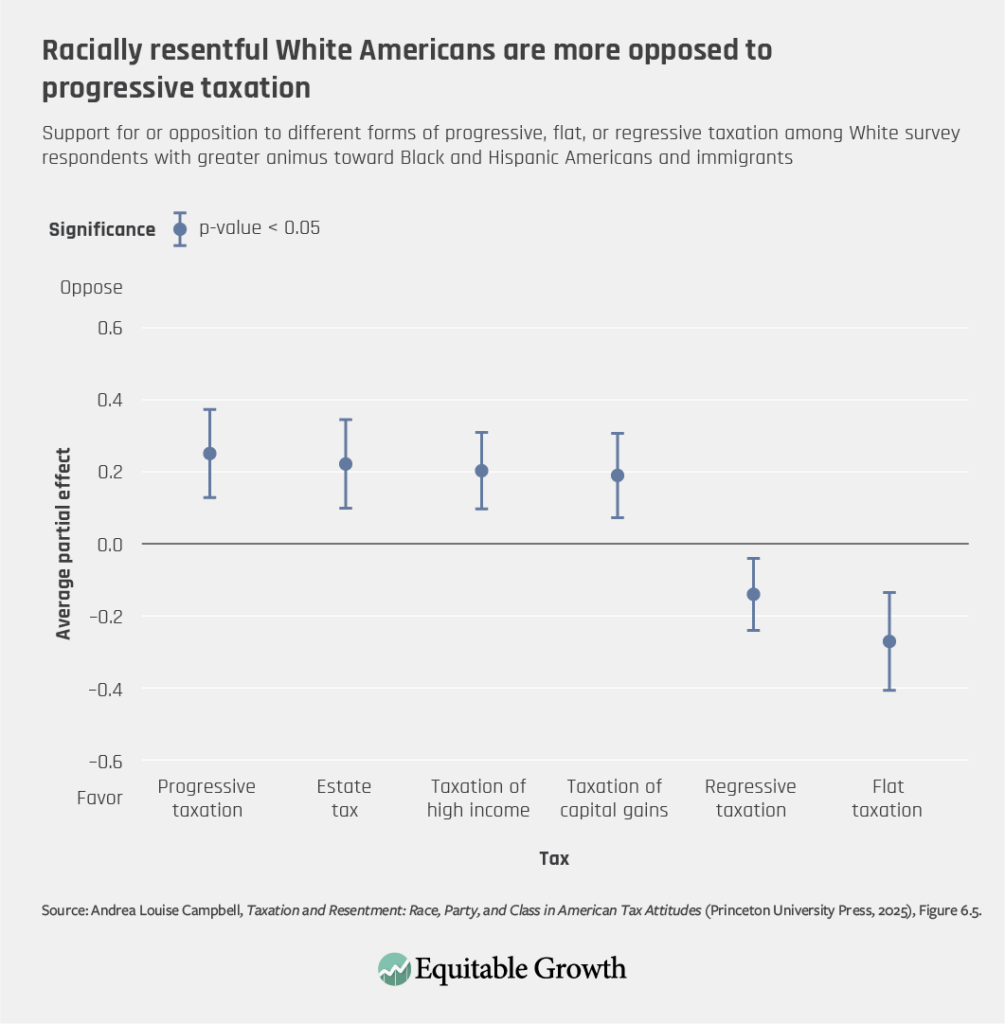

An extensive social science record shows that attitudes toward federal spending are highly racialized, with White Americans who harbor more animus toward Black Americans, Hispanic Americans, and immigrants more likely to want federal spending decreased, especially for income-targeted programs such as Medicaid, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, and the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program, as well as its predecessor, the Aid to Families with Dependent Children program.17 Tax attitudes display the same pattern: The racially resentful are more hostile to taxes, especially progressive taxes, than other White Americans.18 (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

Figure 2 shows that among White survey respondents, those who are more racially resentful are more opposed to progressive taxation in general, and specifically more opposed to a higher estate tax, increased income taxes for high earners, and greater taxation of capital gains. They are correspondingly more favorable toward regressive taxes and flat taxation as a general concept.19 Fanning racial resentment thus helps right-wing politicians gain office and helps the rich in their quest to get progressive taxes reduced.

Attitudes toward tax expenditures have the same opinion structure—a surprise given their supposedly “hidden” nature.20 Tax expenditures are the indirect spending that occurs when the government subsidizes some activity by not collecting taxes. Political scientists have long termed the tax expenditure system “hidden” and “submerged” because people are less likely to recognize a benefit delivered through a tax break than through a direct spending program.21 For instance, people taking the home mortgage interest deduction are less likely to say they benefit from a government program than those living in public housing.22

Survey data I collected for my book on Americans’ tax attitudes show that tax expenditures are not entirely hidden, however.23 Knowledge of the distribution of tax expenditures is not entirely accurate. People overestimate the share of the middle class getting various tax breaks and underestimate the share going to the affluent. Even so, most recognize that the Earned Income Tax Credit goes to lower-income groups and the deduction for charitable giving and the low capital gains rate mainly benefit the rich.

Indeed, Americans know just enough for racial animus to be a factor in their attitudes. Racially resentful White Americans are more likely to want the Earned Income Tax Credit reduced—just like they want direct income support programs such as supplemental nutrition assistance and Medicaid reduced. What’s more, they are more supportive of tax breaks that help the rich, just as they are more supportive of decreasing progressive taxes. This pattern also helps the well-off and the truly rich, as the top 10 percent of U.S. households get nearly half of total tax expenditure benefits while the top 1 percent alone get one-quarter.24

Attitudes toward federal spending, indirect spending through the tax code, and taxes themselves all have the same pattern: The racially resentful dislike progressive measures, which are the very same provisions that the rich seek to erode. Right-wing politicians readily play on these racialized sentiments and use them to deliver tax cuts for their rich backers, while exploiting their mass base to deliver plutocracy.

What can be done?

For decades, the rich have capitalized on the complexities of the U.S. tax system and right-wing politicians’ obfuscation of the realities of that system to get their taxes reduced. The result is that the burden of funding federal, state, and local governments has shifted toward middle- and upper-middle-income households, even as the incomes and wealth of the truly rich have soared.25

The combined tax and spending provisions of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act that President Trump signed into law in July 2025 literally redistribute from the poor to the rich, while leaving middle-income taxpayers barely better off than they were before.26 Once again, the rich get a lot out of a Republican tax law while everyone else gets little, stoking the perpetual dissatisfaction with the system that right-wing populists will be able to call on the next time they wish to cut taxes.

Beyond the redistributive issues, tax revenues in the United States are arguably too low, given the public’s spending preferences. Politicians on the right commonly claim that federal budget deficits and the ballooning national debt are due to a “spending problem.” But budget deficits also are due to a revenue problem. Total taxes as a share of Gross Domestic Product are roughly the same now as they were in the mid-1960s, even as the U.S. population has aged over time, medical technology has advanced, and infrastructure has crumbled.

Large majorities of Americans support the three big domestic social policy programs—Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid—even if the Republican donor class does not.27 And an increasing share of Americans—58 percent as of mid-July 2025—say President Trump has “gone too far in cutting federal government programs.”28 And yet, right-wing politicians’ long-fanned hostility to taxes and appeals to racial animus have kept large shares of the U.S. public on board with both a low-tax regime and a decreasingly progressive one.

It is difficult to know what can be done. Politicians on the left certainly should speak more clearly about the distributional consequences of the full array of U.S. taxes and the decline of progressivity over time, even though politicians on the right will continue to obscure the true tax burdens in U.S. society. Left-wing politicians also should highlight the implications of low revenues for spending, especially on cherished social programs.

In terms of reforms to tax policies, efforts should go toward identifying taxes that the rich can less easily avoid. One problem with the current revenue mix is that the rich have a great deal of latitude to shift their sources of income to those most lightly taxed, and they often do not face third-party reporting as wage earners do. The financial transaction tax that economists Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman at the University of California, Berkeley and Sens. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) and Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) have proposed might help address the problem.29

Some states have made their systems more progressive by adopting so-called millionaires’ taxes that add new brackets and tax rates at the top end of the spectrum. Such heightened income taxes do not overcome the problem with source-shifting, but state lawmakers should know that the usual objection to heightened taxes—that rich people will move out of state because of increased taxes—is not backed by evidence.30 Most rich people do not move away because of high taxes because they are attracted by the amenities that particular states and cities offer, just like everyone else.

Peer nations in Europe pair progressive income taxes with regressive consumption taxes, mainly the value-added tax, which nearly every country has except the United States and a few other holdouts. Value-added taxes help fund the more expansive social policy benefits available in European countries, such as universal health insurance, paid sick leave, and paid family leave. To be sure, regressive payroll taxes play a role in the United States, funding Social Security and part of Medicare, but the array of social programs is far less expansive than in Europe and excludes entire categories of social protections.

Imagine a universal “care” agenda in the United States funded by a value-added tax that helps provide paid sick and parental leave and long-term care and that alleviates the pressures associated with caregiving for the young and the old—pressures that are acute for the middle class. The difficulty in the United States is that achieving the European-style bargain—regressive taxes paired with progressive benefits—would be extremely difficult, given hostility to direct spending programs and the highly racialized concerns about who is deserving that have long dominated U.S. discourse and public opinion about social programs.

Conclusion

Perhaps the crises in federal spending and deficits that the One Big Beautiful Bill Act will exacerbate will force a reckoning with the level and form of U.S. taxation. Alternatively, its tax cuts for the rich may further enrage nonrich taxpayers and make them vulnerable to future anti-tax entreaties and the next round of tax cuts that favor the rich, even as they are hit with the Trump administration’s regressive new tariffs on consumers and businesses. Rinse and repeat.

The incentives for President Trump and Republican lawmakers in Congress to lean into the obfuscation of right-wing populism and yet again tap into Americans’ confusion and freeform tax anger will be strong indeed.

About the author

Andrea Louise Campbell is the Arthur and Ruth Sloan Professor of Political Science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Did you find this content informative and engaging?

Get updates and stay in tune with U.S. economic inequality and growth!

End Notes

1. Congressional Research Service, “U.S. Federal Government Revenues: 1790 to the Present” (2006), Table 2.

2. Seniboye Tienabeso, “Warren Buffett and His Secretary on Their Tax Rates,” ABC News, January 25, 2012, available at https://abcnews.go.com/blogs/business/2012/01/warren-buffett-and-his-secretary-talk-taxes/.

3. Steve Wamhoff, “Who Pays Taxes in America in 2024?” (Washington: Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, 2024), available at https://sfo2.digitaloceanspaces.com/itep/ITEP-Who-Pays-Taxes-in-America-in-2024.pdf.

4. Andrea Louise Campbell, Taxation and Resentment: Race, Party, and Class in American Tax Attitudes (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2025),Table 3.2, p. 63.

5. Karlyn Bowman, Heather Sims, and Eleanor O’Neil, “Public Opinion on Taxes: 1937 to Today,” (Washington: American Enterprise Institute, 2017), pp. 37–47.

6. Vanessa Williamson, Read My Lips: Why Americans Are Proud to Pay Taxes (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2017). On moral framings around taxes, see Ruth Braunstein, My Tax Dollars: The Morality of Taxpaying in America (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2025).

7. Campbell, Taxation and Resentment: Race, Party, and Class in American Tax Attitudes, Figure 3.11.

8. Campbell, Taxation and Resentment: Race, Party, and Class in American Tax Attitudes, Chapter 4.

9. The average federal, state, and local tax rate for the top 1 percent was around 40 percent in 1980 and 25 percent in 2016—and even lower at the very top. The top 10 percent paid around 30 percent in 1980 and 25 percent in 2016. See Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman, “The Rise of Income and Wealth Inequality: Evidence from Distributional Macroeconomic Accounts,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 34 (4) (2020): 3–26, Figure 5.

10. Jesse Eisenger, Jeff Ernsthausen, and Paul Kiel, “The Secret IRS File: Trove of Never-Before-Seen Records Reveal How the Wealthiest Avoid Income Tax,” ProPublica, June 8, 2021, available at www.propublica.org/article/the-secret-irs-files-trove-of-never-before-seen-records-reveal-how-the-wealthiest-avoid-income-tax.

11. Campbell, Taxation and Resentment: Race, Party, and Class in American Tax Attitudes, Chapter 3.

12. Congressional Budget Office, “The Distribution of Household Income, 2019” (2022), exhibit 13, available at www.cbo.gov/system/files/2022-11/58353-HouseholdIncome.pdf; Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, “Who Pays? A Distributional Analysis of the Tax System in All 50 States” (2024), Figure 6, available at https://sfo2.digitaloceanspaces.com/itep/ITEP-Who-Pays-7th-edition.pdf.

13. David S. Mitchell, “Six Years Later, More Evidence Shows the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act Benefits U.S. Business Owners and Executives, Not Average Workers” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2023), available at https://equitablegrowth.org/six-years-later-more-evidence-shows-the-tax-cuts-and-jobs-act-benefits-u-s-business-owners-and-executives-not-average-workers/.

14. Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center, “What Are Pass-Through Businesses?” (2024), available at https://taxpolicycenter.org/briefing-book/what-are-pass-through-businesses.

15. Thomas Byrne Edsall and Mary D. Edsall, Chain Reaction: The Impact of Race, Rights, and Taxes on American Politics (New York: W. W. Norton, 1991).

16. Camille Walsh, Racial Taxation: Schools: Segregation, and Taxpayer Citizenship, 1869-1973 (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2018).

17. Martin Gilens, “’Racial Coding’ and White Opposition to Welfare,” American Political Science Review 90 (3) (1996): 593–604; Katherine Krimmel and Kelly Rader, “The Federal Spending Paradox: Economic Self-Interest and Symbolic Racism in Contemporary Fiscal Politics,” American Politics Research 45 (5) (2017): 727–54.

18. Campbell, Taxation and Resentment: Race, Party, and Class in American Tax Attitudes, Chapter 6.

19. Campbell, Taxation and Resentment: Race, Party, and Class in American Tax Attitudes, Figure 6.5.

20. Christopher Howard, The Hidden Welfare State: Tax Expenditures and Social Policy in the United States (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1997).

21. Ibid.; Suzanne Mettler, The Submerged State: How Invisible Government Policies Undermine American Democracy (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2011).

22. Mettler, The Submerged State: How Invisible Government Policies Undermine American Democracy , p. 38.

23. Campbell, Taxation and Resentment: Race, Party, and Class in American Tax Attitudes, pp. 185–88.

24. Daniel Berger and Eric Toder, “Distributional Effects of Individual Income Tax Expenditures After the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act” (Washington: Tax Policy Center, 2019), available at www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/100346/distributional_effects_of_individual_income_tax_expenditures_after_the_2017_tax_cuts_and_jobs_act_1.pdf.

25. Saez and Zucman, “The Rise of Income and Wealth Inequality: Evidence from Distributional Macroeconomic Accounts,” Figure 5.

26. Congressional Budget Office, “Distributional Effects of H.R. 1, the One Big Beautiful Bill Act” (2025), available at www.cbo.gov/publication/61387.

27. Linley Sanders, “Americans Want Medicaid and Food Stamps Maintained or Increased, AP-NORC Poll Shows,” Associated Press, June 16, 2025, available at https://apnews.com/article/poll-government-spending-medicare-medicaid-social-security-0ccb0538c06d715b43bbbcaa4a1348cf; Benjamin L. Page, Larry M. Bartels, and Jason Seawright, “Democracy and the Policy Preferences of Wealthy Americans,” Perspectives on Politics 11 (1) (2013): 51–73.

28. Ariel Edwards-Levy, “Roughly 6 in 10 Americans oppose Trump’s megabill, CNN poll finds,” CNN, July 16, 2025, available at www.cnn.com/2025/07/16/politics/trump-megabill-one-big-beautiful-bill/

29. Josh Bivens and Hunter Blair, “A Financial Transaction Tax Would Help Ensure Wall Street Works for Main Street” (Washington: Economic Policy Institute, 2016), available at www.epi.org/publication/a-financial-transaction-tax-would-help-ensure-wall-street-works-for-main-street/.

30. Cristobal Young, The Myth of Millionaire Tax Flight: How Place Still Matters for the Rich (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2017).

Stay updated on our latest research