Employers can alleviate the U.S. child care crisis, but they cannot be the primary solution

The U.S. Department of Commerce last month announced new requirements for semiconductor manufacturers seeking funding under the CHIPS and Science Act of 2022—a key component of the Biden Administration’s industrial strategy approach to economic policy. One of these requirements is that larger chip manufacturers must have a plan for supporting their workforces’ child care needs to access this new funding.

Employers—through the taxes they pay and benefits they provide—have an important but delicate role to play in the U.S. child care crisis. Employer-supported child care helps defray essential costs paid by employees, ensuring firms that otherwise freely benefit from the child care system have some necessary skin in the game. A policy agenda that promotes employer-sponsored child care without other public investments, however, could have unintended consequences for the broader U.S. labor and the overall child care market.

This column discusses how employers benefit from the child care system, opportunities and risks posed by employer-sponsored child care, and options within the CHIPS Act, including employers’ direct engagement with existing child care providers that can strengthen local child care markets across the United States.

Employers reap the benefits of their employees’ unsustainable child care costs

The U.S. child care system is primarily funded by tuition fees paid by families, with the median price ranging from $5,357 to $17,171 a year, depending on location, children’s ages, and the type of child care provider. Parents pay these high costs because they get something in return, such as peace of mind that their child is safe, and the time to pursue other activities, including education, job training, and work. In facilitating these activities, child care creates economic benefits far beyond just the families that use and pay for it.

Employers and U.S. workers without children reap the benefits of a mostly privatized child care system without bearing significant financial costs. More specifically, employers benefit from a more diverse, educated, and sizeable labor force. Firms then have a larger pool of potential workers to choose from, allowing them to hire more easily and find the best possible matches for their open positions, which supports productivity across the U.S. economy. This spillover of benefits—what economists call a positive externality—is one of the reasons the U.S. Department of the Treasury asserts child care is a failed market.

The current child care system, however, limits these benefits. Workers who cannot bear the high costs of child care alone are locked out of the U.S. labor market, unable to match into good jobs. Bringing other beneficiaries of the child care system—employers and nonparents—into the funding of these services would bolster the U.S. labor market and support the overall stability of the child care market, all while moderating costs on families. Publicly funded universal child care—just like public kindergarten through 12th grade education, which is supported by taxpayers regardless of parenthood status—would provide a social and economic good worthy of public support.

Robust public investment, potentially in the form of direct support to child care providers and progressive subsidy payments to families through existing tax revenue, would meaningfully achieve this goal. With the implementation of the CHIPS Act, the Biden Administration is probing an intermediary fix: employer-sponsored care.

As this column will detail below, there are tangible benefits to this approach, but a broader policy strategy that relies on employers first may have unintended consequences for labor and child care markets in the longer-term.

Child care requirements for CHIPS and Science Act funding recipients

But first, let’s unbundle the CHIPS and Science Act. The new law provides $280 billion in domestic research and manufacturing of semiconductors, and is a cornerstone of the Biden Administration’s industrial strategy approach to economic policy. Separating industrial policy from traditional corporate welfare—taxpayer support of already profitable industries—are the contingencies and requirements placed on funding opportunities. The U.S. government takes a more direct hand in shaping industries toward socially and economically optimal outcomes.

Recently, the U.S. Department of Commerce announced one of these contingencies: manufacturers seeking more than $150 million in direct funding via the CHIPS Act must submit with their application a “plan to provide their facility and construction workers with access to child care.”

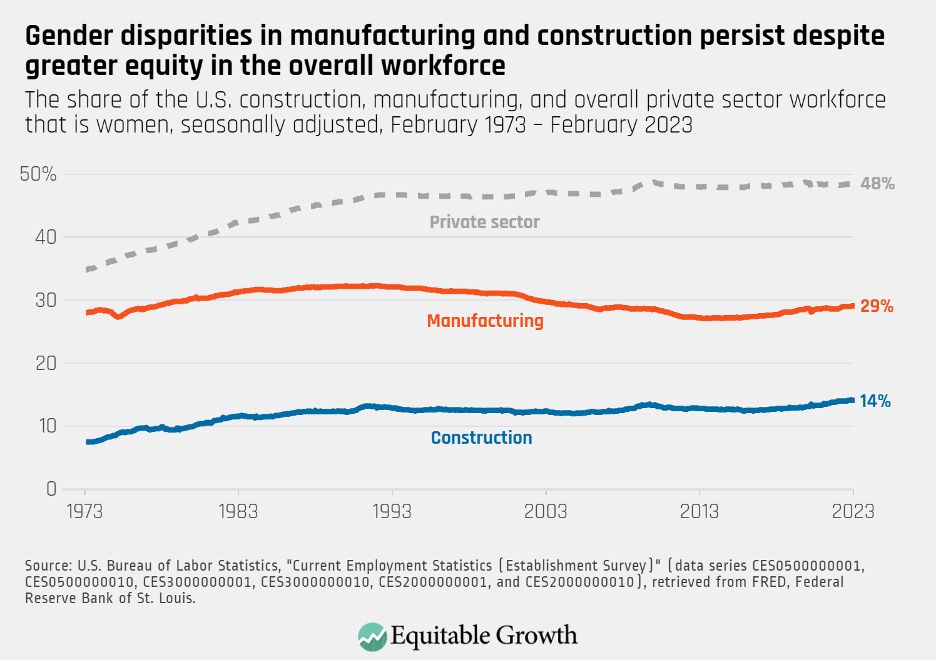

Motivating this requirement is the reality that the United States will need to grow the construction and manufacturing workforce to accomplish the production goals in the CHIPS Act and other industrial policy initiatives. Large gender disparities in these two sectors suggest that this growth may be dependent on successfully recruiting more women both into the labor force and these jobs. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

Research has long identified the link between accessible and affordable child care and maternal labor force participation. By building up child care infrastructure around the semiconductor industry, the Biden Administration hopes to create a pathway between new women workers and this critical sector.

In March 2023, the U.S. Department of Commerce released its workforce development planning guide for CHIPS Act applicants, providing new details on these child care requirements. Rather than prescriptive measures, applicants are presented with several funding options depending on the needs of their workforce and their communities’ local child care market. The four primary models presented by the workforce guide include:

- On-site care that is fully operated by the employers

- On-site care that is fully operated by external contractors

- Cash assistance (vouchers) for workers to purchase off-site care

- Direct sponsorship of preexisting, off-site child care providers

The CHIPS Act’s child care requirements stem from an established practice of tying employer-benefits and other elements of job quality to federal funding. In 2016, for example, the Obama Administration required federal contractors to provide paid sick leave to their employees. More recently, President Biden issued an executive order mandating salary transparency among federal contractors.

But by requiring these manufacturers to engage with third-party child care providers or potentially supplant child care services available elsewhere in the market, the CHIPS Act involves entry into the child care market that regulators and manufacturing must carefully navigate.

Employer-sponsored care may help some workers access child care, but the practice at a larger scale poses broader risks

While some large firms proactively provide child care benefits to attract and retain talent, data shows that most employers regard care needs as a private matter of personal responsibility. In 2021, for example, only 11 percent of the civilian workforce had employer-provided child care benefits, including just 8 percent of those in “goods producing industries” such as semiconductor manufacturing.

By requiring employers to plan for potential child care issues, the CHIPS Act is forcing some firms to contend with a challenge they may have otherwise ignored. This should yield tangible benefits for employees in this sector, but policymakers must be thoughtful as more employers find themselves in the child care business. They need consider whether:

- Employer-sponsored child care can address coverage gaps for those with the greatest need

- Tying benefits to employment can impede movement through the labor market

- Employer-sponsored child care may exacerbate gender discrimination

- Employer-sponsored benefits can lead further down the path of privatization

Let’s consider each of these situations briefly in turn.

Employer-sponsored child care can address coverage gaps for those with the greatest need

Employer-sponsored child care remains a rare benefit in the United States, but research indicates that it can be highly valuable for certain demographics. One study by Taryn Morrissey of American University and Mildred E. Warner of Cornell University finds that child care vouchers provided by a university employer were effective in reaching workers with the highest needs, including part-time workers and those with more complex child care requirements. A related study finds that workers who used these vouchers were more committed to their employers and reported less work/family stress.

And more recent research from Audrey Altura of Harvard University finds that women highly value on-site child care options and are more likely to apply for more intensive management jobs when on-site care is available for the extended-hours they need.

For U.S. workers who struggle to access and pay for child care—because they live in low-supply areas, do not qualify for financial support, or work nonstandard hours—employer-sponsored care provided on site or off site could meaningfully address their care needs. All four delivery models recommended in the CHIPS Act’s guidance (detailed above) would make care more accessible for these families. In different labor and child care markets, however, some delivery models carry more risk than others.

Tying benefits to employment can impede movement through the U.S. labor market

A parent’s child care needs may be similar whether they are working at a semiconductor plant, an auto factory, a fast-food restaurant, or a retail store. But if only one of these employers offers government-supported child care benefits, then it can create less competitive and less productive overall labor market conditions.

Coupling employment with essential benefits can keep workers in jobs they otherwise might leave for fear of losing access to those benefits if they move to a new employer, become self-employed, or exit the labor force. This phenomenon, known as “job lock,” is widely understood in the context of employer-provided health insurance and leads to significantly reduced job mobility.

This added friction in the U.S. labor market reduces competition. It prevents productivity-improving job changes because employees may not move to a job that’s a better match for their skills. And it can stifle entrepreneurship as potential small business owners weigh the cost of self-financing their benefits without publicly supported social infrastructure.

Providing on-site care and vouchers carry the greatest risk for stifling job market mobility, as they tie benefits directly to employment conditions. Engaging and sponsoring community child care providers, however, carries the least risk of benefit-induced job lock as it may promote a healthier overall child care market even for nonemployees.

Employer-sponsored child care may exacerbate gender discrimination

Policies such as paid child care and paid family and medical leave can encourage women’s labor force participation and improve equity in the workplace, but policy design matters. When fringe benefits are born primarily by employers and systematically used by some workers more than others, it can drive hiring, pay, and promotion discrimination for employers seeking to cut costs. Research shows that older and less healthy workers, for example, can experience discrimination in the workplace when employers face higher costs associated with these employees’ health insurance.

Already, women face greater workplace discrimination, carrying the predominant weight of caregiving and domestic responsibility in most families. Child care benefits that raise employers’ costs the more they are used may discourage the hiring and advancement of qualified women and caretakers, compounding this preexisting caregiver penalty. Researchers in Chile, for example, have documented a gendered wage penalty following a policy mandating employer-provided child care benefits.

Among the care models available for CHIPS Act recipients, a voucher or subsidy system offers the greatest risk of unintended discrimination, as the costs of providing care are directly attached to an employee’s care needs. On-site care likely mitigates this risk somewhat by driving down the potential marginal cost of new employees with care needs. The engagement and sponsorship of community child care providers carries the least risk because the costs to employers could be arranged upfront and separate from the composition of the workforce.

Employer-sponsored benefits can lead further down the path of privatization

Employer-sponsored care may fill a critical immediate need, but a policy program that systematically preferences this particular type of benefit may impede more equitable, more productive, and ultimately more affordable child care reform down the road.

The U.S. health insurance model is a primary example of how employer-provided benefits can become problematically entrenched in U.S. policy. What started as a discretionary benefit to attract employees in the 1940s amid World War II became legally codified over the decades as a taxpayer-supported, mandated benefit paid for by many employers.

Today, more than half of the U.S. population gets healthcare through employers, subsidized to the tune of $200 billion annually in tax exemptions. The result is a health care system that, while popular with those who can access care, is complex and expensive, with large coverage gaps, and is nearly impossible to untangle.

While the size of the CHIPS Act’s child care provisions is small in relation to the broader U.S. child care market, and thus unlikely to radically shift the trajectory of child care reform in the United States, policymakers should be cautious by avoiding an employer-first approach to child care benefits that replicates the misguided approach of U.S. healthcare.

Policies that nudge employers to provide child care can offer some immediate benefits to employees in need, but they cannot meaningfully replace the comprehensive public investment necessary to provide equitable, affordable, and high-quality child care for all U.S. families and create a more sustainably productive U.S. economy.

Tax payments and investments in child care markets offer the greatest potential for firms to responsibly defray employees’ costs

Expanding accessible and affordable child care options, particularly those that can accommodate for nonstandard schedules, should have a positive effect on women’s labor force participation and, in the context of the CHIPS and Science Act, help the United States meet its manufacturing goals. All of the care models recommended in the CHIPS Act’s guidance—on-site care run by employers, on-site care run by contractors, a voucher system, and child care provider sponsorship—should all be expected to support employees’ short-term care needs.

Beyond just semiconductor manufacturers, employers have a role to play in addressing the U.S. child care crisis. The most direct and equitable strategy would be robust, public investment in the child care market financed through the federal tax systems. Income and corporate taxes paid into the U.S. Department of the Treasury would be redirected to the child care system through progressive subsidy payments to families and direct support to providers. This model provides the greatest support to the child care system while spreading the costs most widely.

At the state level, some policymakers are exploring a new payroll tax on employers to fund large-scale reform. New York State, for example, recently considered a progressive payroll tax, ranging from 0.5 percent to 1 percent of payroll expenses depending on firm size, to cover expanded subsidy payments to families.

A payroll tax model would provide dedicated funding for the child care market and ensure employers are paying a share of the costs. This model may, however, be more vulnerable to the ebbs and flows of the business cycle, and employers are likely to pass some of the tax onto their employees.

The child care requirements in the CHIPS and Science Act introduce a new method of compelling employers to contribute to their workers’ child care needs. While regulators are offering flexibility as to how semiconductor producers comply with the law’s child care requirements, some methods are better suited to limit unintended consequences for local labor and child care markets while investing in the health of local child care systems.

Regulators should encourage manufacturers to engage not just with their workforce, but with their community’s child care systems directly, too. Sponsoring local child care providers can help raise capacity across the local market without crowding out other families or tying child care access directly to conditions of employment.

One strategy promoted by the U.S. Department of Commerce particularly stands out: demand guarantees. With this approach, companies will guarantee a certain level of financial support to providers, reducing the risk that actual care needs differ from what was projected. This will help providers offer new services in child care deserts or during nonstandard hours when they otherwise may not be able to, due to hidden or lower-than-profitable demand.

There is, of course, no one-size-fits-all solution to providing child care amid a nationwide child care crisis. Semiconductor firms will likely need to engage in some combination of vouchers, on-site care, and sponsoring child care providers to ensure adequate care to their workforce. U.S. regulators reviewing these child care plans should be cognizant of the opportunities and potential risks of employer-provided care and work with applicants on an approach that supports, rather than supplants, local child care markets.

Conclusion

In the coming months, U.S. Department of Commerce program officers will begin the complex task of distributing tens of billions of dollars to semiconductor manufacturers through the CHIPS and Science Act. As part of this process, regulators will have to weigh how well semiconductor manufacturers are prepared to provide the needed child care support to their potential workforce.

The child care provisions of the CHIPS Act are a novel melding of industrial policy and the care economy—a necessary intervention to ensure the United States has the construction and manufacturing workforce it needs to accomplish its infrastructure and production goals.

Despite the large investment the government is making in semiconductor productions, the ramifications of the CHIPS Act’s specific child care provisions are likely to be limited in the overall child care market. Yet a larger policy strategy that nudges employer-involvement in the child care system without comprehensive public investment may have unintended consequences for the broader labor and child care markets. With the CHIPS Act, regulators have an opportunity to set an example for how employers should account for their workers’ child care needs. To the extent possible, prioritizing child care plans that support preexisting providers or expand new options in the community will set the tone for how employers and the government can work together to support the child care sector—at least until robust, public investment in care makes such efforts no longer necessary.