Emergency paid leave during the COVID-19 pandemic offered essential protections for U.S. workers

Overview

When the COVID-19 pandemic swept across the United States in early 2020, it didn’t just bring about a public health emergency. It also exposed a longstanding weakness in the U.S. labor market—that many workers lack access to paid leave.

In April 2020, U.S. unemployment surged to its highest level in more than 75 years, leaving millions of families vulnerable to lost income as they faced a nationwide economic shutdown. Without paid leave, workers who were not laid off faced a stark choice: Show up sick or stay home and lose income on which they depended.

To help Americans manage the shock of the pandemic, Congress passed the Families First Coronavirus Response Act in March 2020. It created the first federal paid leave mandate, albeit only temporary and not for everyone. Importantly, the program targeted the workers most vulnerable to gaps in paid leave coverage: employees at smaller firms and in jobs that could not be done from home.

But did it work?

In a recently published article supported by the Washington Center for Equitable Growth, we dig into this question. Our study is the first to leverage individual employment data to study whether the Families First Coronavirus Response Act successfully expanded access to paid leave when families needed it most.

Our findings point to a clear conclusion: FFCRA paid leave benefits protected workers against the shocks of the COVID-19 pandemic—especially parents of young children—and helped fill a longstanding gap in U.S. social infrastructure at a time when it was needed most. Notably, these lessons extend beyond the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent recession, offering a blueprint for how federal policy can prepare for the next crisis and support working families in the meantime.

Unequal and inadequate paid leave is the norm across the United States

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, we estimate that just 1 in 5 private-sector workers in the United States had any access to paid family and medical leave and 1 in 4 did not have access to paid sick leave. Those without access to paid leave disproportionately worked in smaller firms and in lower-paying jobs—making them already more exposed to the effects of economic or public health crises due to the nature of their occupations and their employers’ vulnerability to economic downturns.

Even among workers who did have access to paid leave, we find that the benefits often fell short of real needs. For example, just 17 percent of private-sector workers had access to 2 weeks of paid sick leave—the timeframe recommended for quarantine if exposed to COVID-19 at the start of the pandemic in 2020. In smaller firms, that number was just 10 percent, and many workers receive far fewer days.

When the pandemic hit the United States in March 2020, forcing an economywide shutdown, workers at small firms and in-person jobs faced the greatest strain from the health and subsequent economic crises, in part due to the longstanding gap in access to paid leave. This inequity meant that these same workers were also the least equipped to absorb the effects of the emergencies.

FFCRA-expanded paid leave in the U.S. economy

The FFCRA emergency paid leave program, effective April 1, 2020 until the end of that year, created two temporary benefits:

- Emergency paid sick leave: Up to 2 weeks of fully paid leave for workers who had COVID-19 symptoms, were quarantining, or caring for sick family members

- Emergency paid family leave: Up to 10 weeks of partially paid leave—at two-thirds of regular wages, subject to a cap—for parents caring for children whose school, place of care, or care provider was closed

By design, these benefits were targeted to those workers who were most likely to lack access to paid leave and whose employment was the most likely to be disrupted by the pandemic. The program was available to workers who had been employed for at least 30 days at firms with fewer than 500 employees. Workers able to telework were excluded from eligibility.

Typically, paid leave benefits are financed through a small payroll tax, which is paid for by employers and employees alike. Yet to ensure that employers were not burdened by the costs of the FFCRA leave programs, the federal government fully reimbursed replacement wages through a refundable payroll tax credit. This funding model is notably unprecedented and reflected the emergency nature of the policy.

Unfortunately, awareness of and participation in the program was low. Surveys at the time suggested that fewer than half of eligible firms and workers knew about or used the benefit. As such, emergency paid leave might have been a policy on paper, but not in practice.

Measuring the effectiveness of FFCRA paid leave

To evaluate how effective emergency paid leave was, we looked at monthly data on paid leave from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey. This survey records whether employees are absent from work each month and whether these absences were paid. It also records the size of the employer and the type of occupation, which allowed us to identify workers at small firms and those who were unlikely to be able to perform their jobs from home. As discussed above, these two characteristics primarily identify workers who were eligible for the policy.

Our analysis focuses on workers in jobs that could not be performed remotely and compares their rate of paid absences from work along the following dimensions:

- Small firms, which were covered by the law, compared to large firms, which were not

- Leave-taking before (January to March 2020) and after (April to June 2020) the pandemic’s onset, relative to these same months in 2018 and 2019, which allowed us to account for normal seasonal patterns in paid leave-taking

By layering these comparisons together using a method known as difference-in-difference-in-differences, we can separate out the effect of the FFCRA paid leave benefits. In other words, we compared differences across three dimensions at once to account for regular seasonal variations and the broader labor market disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

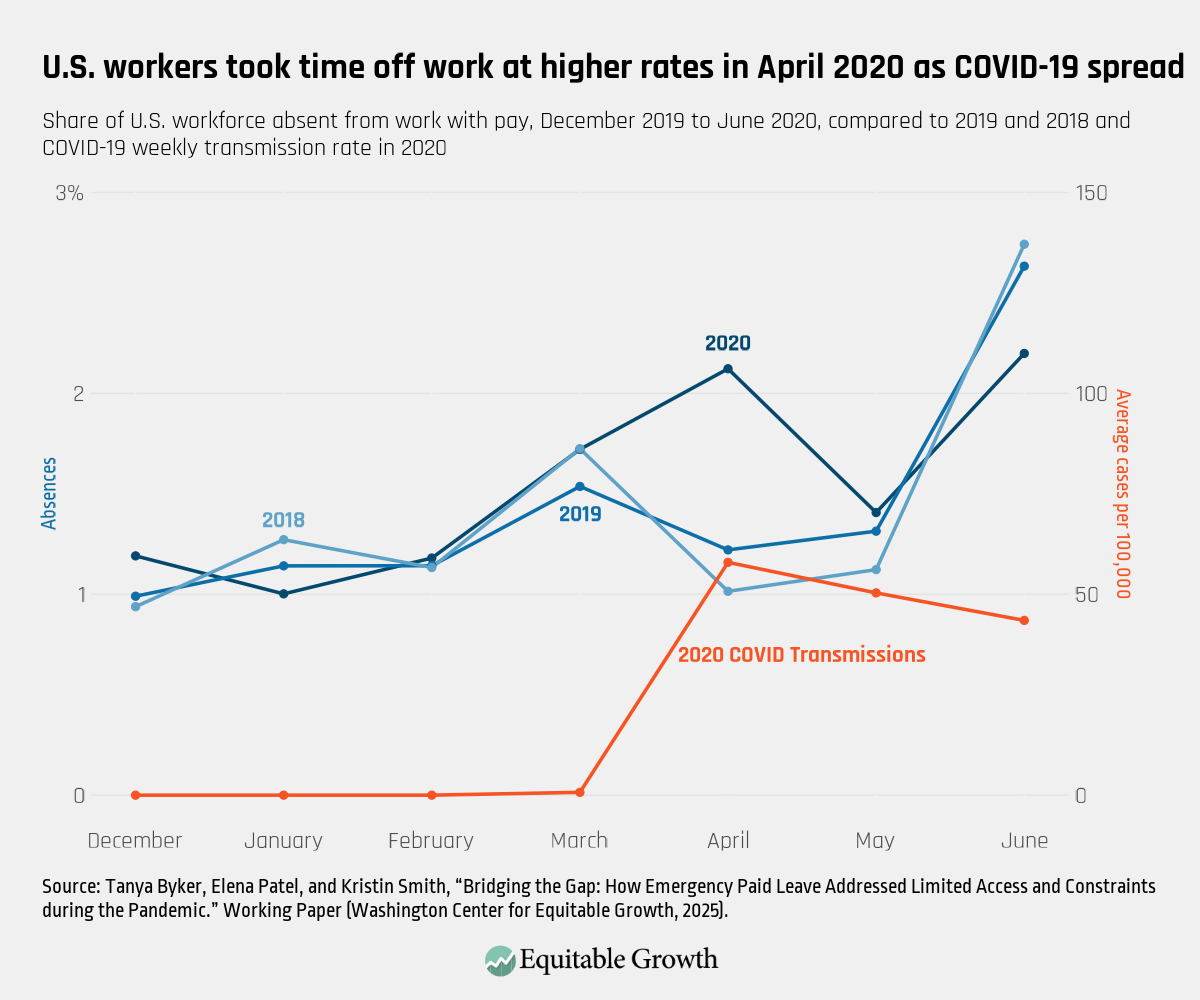

Using the CPS data, we find that paid absences from work spiked in April 2020, when COVID-19 cases began to surge and the U.S. economy shut down. At this time, almost everyone needed to take time off from work, regardless of firm size or telework eligibility. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

What happened next demonstrates the importance of paid leave for the most vulnerable workers in the U.S. economy.

By June 2020, we find that paid absences among workers at large firms (those not covered by the emergency paid leave) fell below normal levels, suggesting that these workers had already exhausted their limited leave during the April COVID-19 surge and economic shutdown. In contrast, workers at small firms continued to take paid leave at higher-than-usual rates as the pandemic wore on.

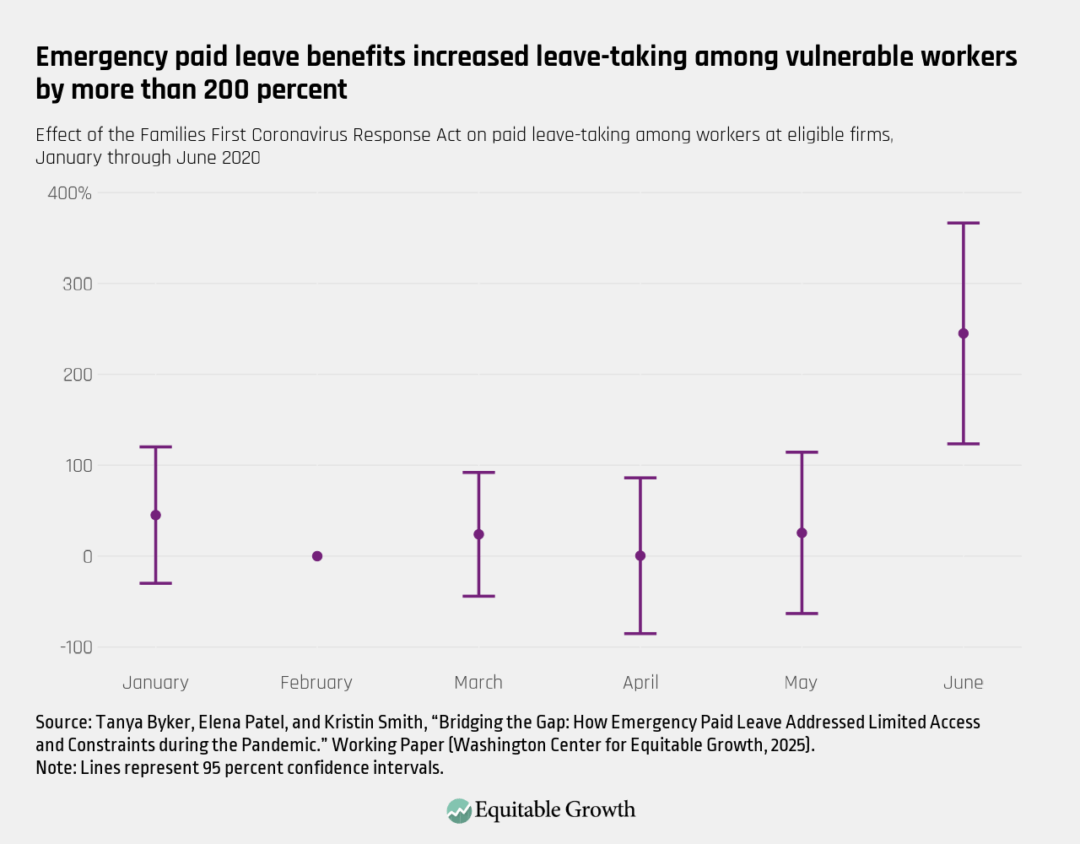

Indeed, we estimate that access to FFCRA emergency benefits increased the likelihood of these workers taking paid leave by more than 200 percent, relative to historic norms. In other words, emergency paid leave gave more vulnerable workers the flexibility to meet their ongoing leave needs over time, rather than burning through all their leave in April. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

We then examined differences across U.S. states, depending on the severity of the first COVID-19 wave in April 2020. In states with higher COVID-19 transmission rates, workers were more likely to exhaust whatever paid leave they had during the initial surge, making them more reliant on the new FFCRA benefits as the pandemic wore on.

We also find that covered workers in states with the highest transmission rates were more than 10 times more likely to take paid leave in June 2020 than those in states with the lowest transmission rates. This pattern suggests that the emergency paid leave worked as intended, providing the most relief where the health disruptions were the most severe.

Finally, an underappreciated piece of the Families First Coronavirus Response Act was its innovative expansion of paid leave to address pandemic-related caregiving disruptions. The pandemic ushered in an unprecedented period of school and day care closures. Our analysis shows that mothers of children under age 12 were far more likely to increase their leave-taking in June 2020, while adults without children saw little change.

This result underscores how caregiving—not just illness—was a central driver of the need to take paid leave during the pandemic. Looking ahead, it also highlights the need for paid leave policies that more explicitly address caregiving disruptions, which are rarely covered under standard programs. Even in normal times, families regularly face these challenges—ranging from unexpected snow days to scheduled teacher workdays—making clear that caregiving leave matters well beyond public health crises.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic reminded us that paid leave is not only a perk but also is an essential protection for workers, families, and public health. The Families First Coronavirus Response Act introduced a first-of-its-kind experiment in federal paid leave, and our research shows that it worked. It gave workers the breathing room to meet urgent and ongoing needs, particularly in the states hardest hit by the pandemic, among workers at small firms, and for parents juggling care responsibilities and work.

At the same time, the paid leave benefits were temporary, and they did not cover all U.S. workers. Nevertheless, the law offers three important lessons for the future of U.S. paid leave policymaking:

- Emergency paid leave is feasible. The federal government demonstrated it can step in and provide paid leave quickly, even in a fragmented system where access to paid leave usually depends on employer generosity or state mandates.

- Targeting matters. By focusing on small firms and nontelework jobs, FFCRA benefits reached those with the least access to paid leave. At the same time, this targeting likely limited take-up and awareness, as shown by other research. Broader benefit coverage could increase both the visibility and effectiveness of the policy.

- Caregiving leave is critical. During crises, families don’t just need sick leave; they also need family leave. School and child care disruptions, though less visible, are just as disruptive to work.

The United States remains one of the only advanced economies without a permanent, national paid leave program. The Families First Coronavirus Response Act provides a glimpse into what such a program could achieve by strengthening the resilience and equity of the U.S. labor market, both during and outside of times of crisis.

When Congress and policymakers inevitably revisit a federal paid leave program, they should take this lesson to heart. When emergencies strike, paid leave is not optional—it is essential.

This column draws on findings from “Bridging the Gap: How Emergency Paid Leave Addressed Limited Access and Constraints During the Pandemic,” published in Equitable Growth’s Working Paper Series and forthcoming in the National Tax Journal. We thank the Washington Center for Equitable Growth for supporting this research.

Did you find this content informative and engaging?

Get updates and stay in tune with U.S. economic inequality and growth!

Stay updated on our latest research