“Econ 101” briefing on taxing multinationals brings Hill staffers up to speed on U.S. role in coordinating global crack-down on tax avoidance

The Washington Center for Equitable Growth last week hosted a briefing for Capitol Hill staffers on multinational corporate tax trends and policies—another in our “Econ 101” series for Hill staffers. Over the past few decades, multinationals corporations have grown into economic giants, accounting for more than 30 percent of global Gross Domestic Product and dominating international trade flows. These companies’ cross-border operations raise fundamental questions about how they should be taxed in an increasingly globalized economy.

Our March 28 briefing was led by David S. Mitchell, Equitable growth’s senior fellow for tax and regulatory policy, and Elena Patel, assistant professor at the University of Utah’s Marriner S Eccles Institute for Economics and non-resident senior fellow at the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center. The briefing was timely for Hill staffers because lawmakers around the world are engaged in on-going negotiations to curb the harmful tax competition that has driven corporate tax rates to unsustainably low levels, fueled aggressive and inefficient tax planning, and eroded corporate tax bases.

After years of international negotiations led in large part by the United States, the world in 2021 coalesced around a solution: the Global Tax Deal. This ambitious framework—agreed to by more than 130 countries, including the United States—aims to modernize how large corporations are taxed in an increasingly interconnected global and digital economy. But recent policy shifts by the second Trump administration have introduced fresh uncertainty, throwing the stability of the agreement into question.

Mitchell opened the briefing by describing the U.S. corporate tax, an entity-level tax that applies to C-corporations—so-named based because their tax treatment is governed by subchapter C of the U.S. Internal Revenue Code. These companies are subject to a flat 21 percent corporate tax on their taxable profits, but they can reduce their tax bills by taking advantage of deductions and credits that are designed to influence corporate behavior.

As a result, Mitchell noted that roughly half of large corporations and one quarter of large, profitable corporations do not owe any federal tax each year. The effective tax rate, or the ratio of a firm’s tax bill to profits, reflects the actual tax burden faced by a firm. The nonpartisan Government Accountability Office, the investigative arm of Congress, estimated that the average effective tax rate among large, profitable corporations was just 9 percent in 2021, or less than half of the statutory rate of 21 percent.

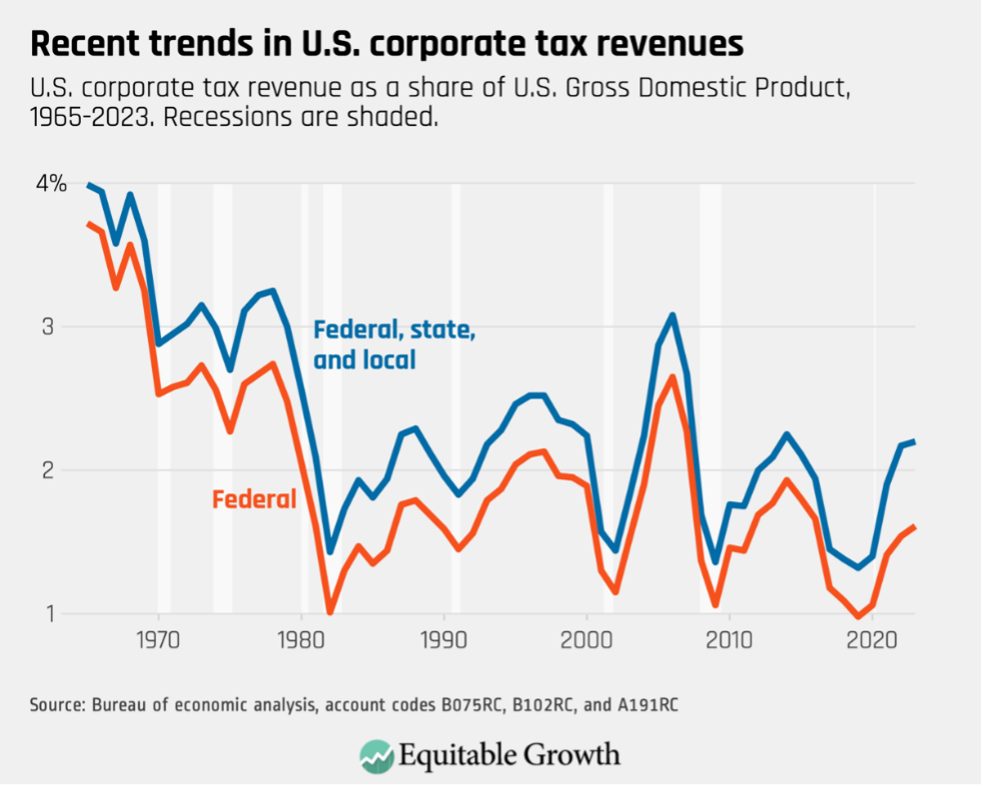

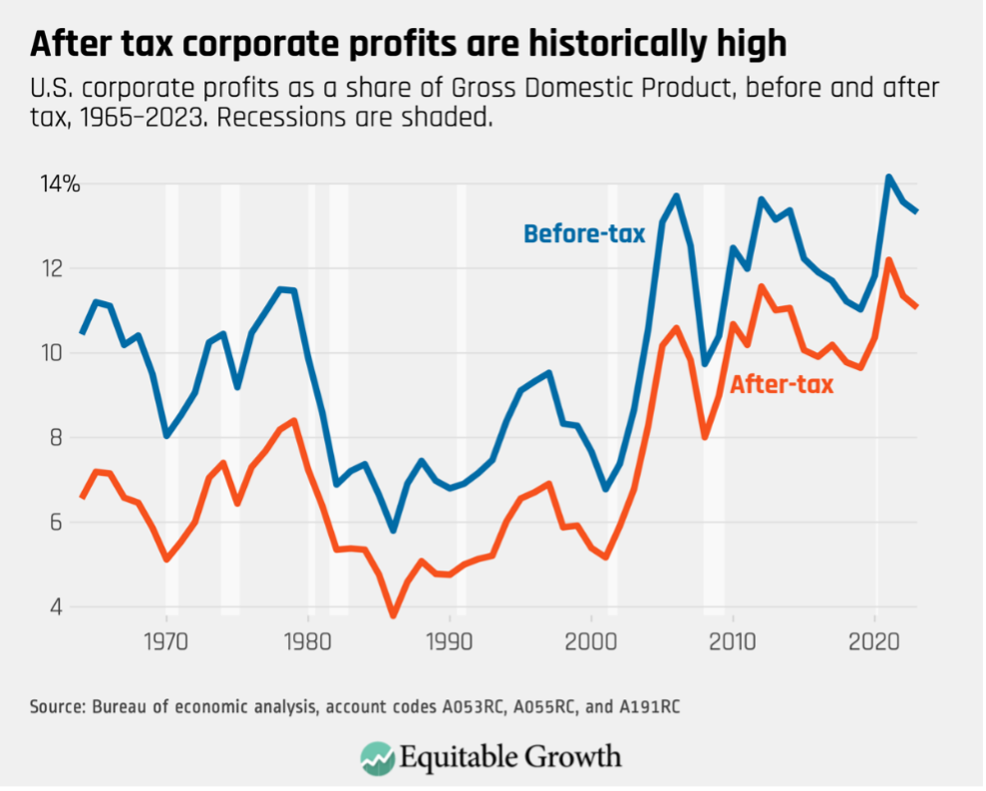

U.S. corporate tax revenue has been relatively flat over the past 40 years, at about 1 percent to 3 percent of GDP, even though corporate profits have nearly doubled. (See Figures 1 and 2.)

Figure 1

Figure 2

One reason is that sophisticated cross-border tax planning undertaken by multinational corporations tends to push taxable profits into low-tax jurisdictions. As Patel explained, multinational corporations choose where to locate assets and sell their products, taking into consideration the myriad of corporate tax rates available to them across the globe. The rise of intangible assets, such as intellectual property, only further complicates these choices because intangible assets are highly mobile and difficult to price, making them an easy vehicle for shifting profits across borders.

In fact, since 2015, about 40 percent of foreign income earned by U.S. multinationals has been booked in just six low-tax countries. This does not necessarily mean that multinationals are outsourcing physical operations or jobs to these countries, but that they also could be using accounting strategies related to transactions between the parent company and its foreign subsidiaries that results in profits being reported there. In response to these trends, countries have begun to undercut each other’s corporate tax rates, leading to a global race to the bottom.

Patel went on to explain how these emerging trends have called into question the fundamental principles of international income tax on which tax treaties and national tax codes have been based. The first right to taxation of corporate income, for example, typically belongs to the country where a company has a physical presence, or what is referred to as its nexus. Yet the advent of digital services introduces questions about where exactly value is being created and the first right to taxation.

For example, if a tech company sells advertisements on its search engine to foreign companies that are viewed only by foreign customers, is the value created by the foreign customers, or is the value created by the servers that run the search engine? These concerns have led some countries to deviate from international norms and unilaterally impose a Digital Services Tax on the gross revenues from search engines, social media platforms, and online marketplaces operating within its borders—actions that have been interpreted as discriminatory by the U.S. government because many of these services are provided by U.S. multinational corporations. Countries that have put in place or have threatened to put in place a Digital Services Tax include the United Kingdom, several countries in the EU, Canada, and India.

The first Digital Services Tax predates the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, which marked a turning point in the U.S. tax treatment of multinational corporations. The tax law replaced the U.S.’s worldwide tax system, which had led to more than $4 trillion in earnings being held offshore to avoid costly repatriation taxes, with a territorial system that only taxes income earned within the United States—more closely aligning with the tax systems of other member nations of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

At the same time, the 2017 tax law introduced three key measures—usually referred to in tax parlance by their acronyms GILTI, FDII, and BEAT—all of which depart from a pure territorial approach to protect the U.S. corporate tax base. GILTI serves as a minimum tax on certain foreign income to discourage profit shifting. FDII provides a preferential tax rate for income earned from certain exports to encourage onshoring. And BEAT prevents the erosion of the corporate tax base through certain deductible payments made to foreign affiliates.

None of these new measures, however, appear to have been successful in bringing the taxation of profits or physical production back to the United States, underscoring the challenges policymakers face by attempting to unilaterally correct for global tax competition. That’s why the Global Tax Deal introduces a two-pillar framework that reflects a cooperative effort to re-align the principles of international corporate taxation to escape the race to the bottom.

Under the first pillar, tax rights pertaining to a portion of the profits (referred to as Amount A in the treaty) of highly profitable, large companies are reallocated to market countries based on the relative size of their consumer base. This first pillar is meant to replace the current patchworked system of Digital Services Taxes and reform the concept of a company’s nexus to acknowledge both its physical and digital presence.

Under the second pillar, participating countries agree to implement a self-reinforcing set of minimum taxes designed to ensure that each affiliate of a multinational pays a 15 percent minimum effective tax rate, regardless of where it operates, and to create incentives for low-tax jurisdictions to raise their rates to meet that minimum. So far, more than 70 countries are in the process of or have already enacted legislation complying with this second pillar. Negotiations concerning the first pillar are ongoing. Notably absent: the United States.

Patel and Mitchell concluded this Econ 101 Hill briefing by emphasizing that ending harmful tax competition requires global cooperation—and that the United States has been a key leader in shaping the Global Tax Deal while protecting U.S. interests. With thoughtful adjustments, parts of the U.S. tax code, such as GILTI, could be adopted to align the U.S. tax code with the Global Tax Deal’s framework. Ultimately, these changes require congressional leadership.

Equitable Growth’s latest Econ 101 briefing will enable congressional staff to be better prepared to navigate the complex tax issues that underlie this important debate and ensure that the United States remains a leader in shaping fair and stable international tax rules.

To learn more, please review the presentation slides from the March 28 Econ 101 briefing.

Did you find this content informative and engaging?

Get updates and stay in tune with U.S. economic inequality and growth!