Doubling down on cuts to the IRS is bad for the federal budget and for tax fairness in the United States

The U.S. Congress recently announced a bipartisan budget deal for fiscal year 2024 appropriations for the U.S. federal government. The budget is largely consistent with the framework agreed to in the spring of 2023, but with one major—and unfortunate—exception: an accelerated $10 billion cut to the IRS’s tax enforcement budget.

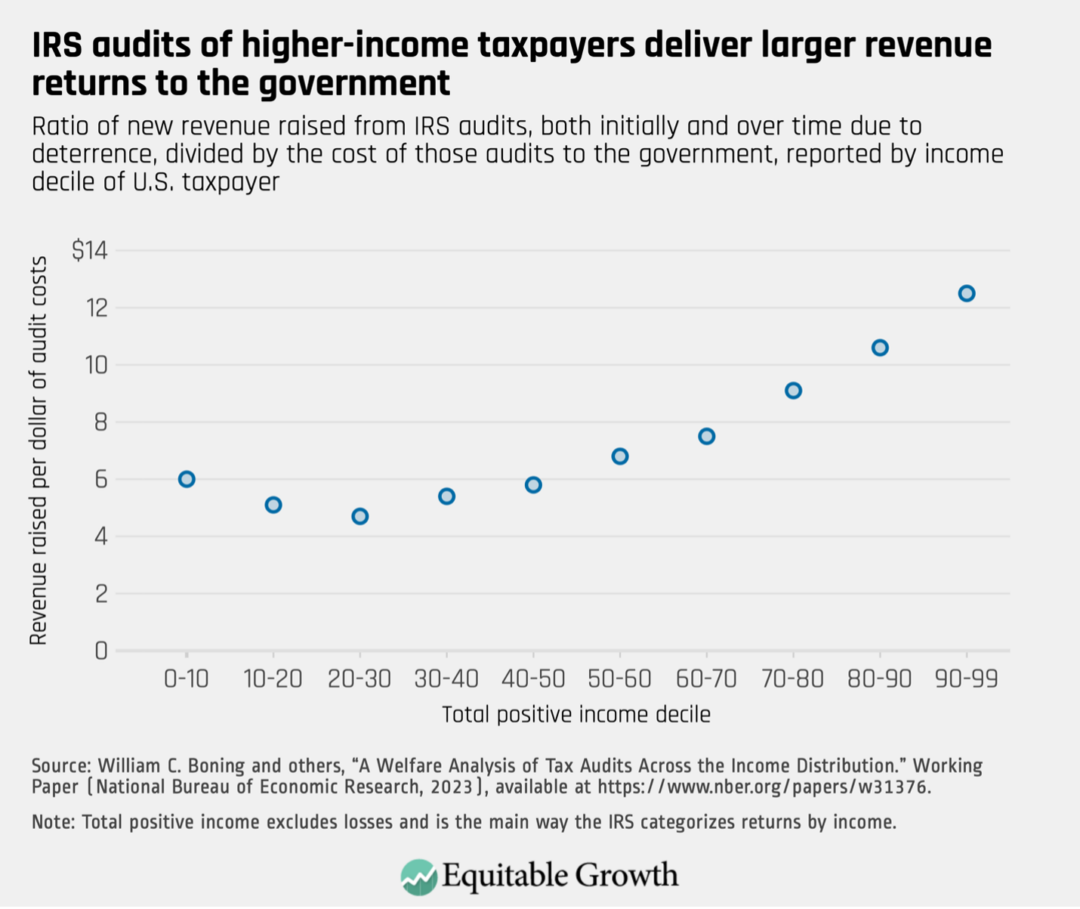

This proposed cut comes despite rigorous academic evidence that proves that tax enforcement—and particularly the high-income audits that these funds would be used for—is highly cost effective and generates significant returns to the government. Indeed, a recent, cutting-edge study by William C. Boning from the U.S. Treasury Department, Nathaniel Hendren and Ben Sprung-Keyser from Harvard University, and Ellen Stuart from the University of Sydney finds that an additional $1 spent auditing taxpayers with incomes above the 90th percentile yields more than $12 in federal revenue, making it an incredibly efficient way to raise money.

The co-authors find that this additional revenue comes from two channels. First is the direct effect of identifying and correcting for underpayment in the auditing process—that is, the funds retrieved from auditing taxpayers who did not properly report their incomes and collecting additional revenue as a result. Second, the authors find additional revenue from an indirect, individual deterrent effect that comes from audited individuals being more likely to fully comply with tax rules in the years after an audit. In other words, following an IRS audit, taxpayers tend to correctly report their incomes and pay what they owe.

The study does not attempt to quantify the potential general deterrent effect in which higher audit rates dissuade nonaudited taxpayers to more closely comply with the law. But if this were found to be the case, then that would only increase the financial return that comes from investment in the IRS.

Auditing high-income taxpayers is more complicated and expensive for the IRS than auditing lower-income taxpayers, who tend to have simpler returns. This paper, however, proves that the returns to auditing high-income taxpayers more than makes up for those additional costs. Indeed, the authors find that audits of below-median-income taxpayers delivers just $5 for every $1 spent—less than half of the returns for auditing high-income taxpayers. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

The study also looks at audits of taxpayers in the top 1 percent of earners. Though the small sample size for that narrow income band limits the precision of their estimates, the authors find even larger returns on investment for this group: $18.20 in revenue for every $1 spent on auditing those between the 99th percentile and the 99.9th percentile— and a whopping 36-to-1 return for those in the top 0.1 percent.

This analysis from Boning and his co-authors builds on previous Equitable Growth-funded research from John Guyton and Patrick Langetieg from the Internal Revenue Service, Daniel Reck of the University of Maryland, Max Risch from Carnegie Mellon University, and Gabriel Zucman of the University of California, Berkeley. That paper finds that random IRS audits underestimate tax evasion at the top of the income distribution in the United States because of the wealthy’s use of sophisticated tax evasion tactics. Guyton and his co-authors estimate that if the IRS had more resources to uncover this abuse, it could raise an additional $175 billion annually.

This is one reason why the U.S. Treasury Department had plans to use additional IRS funding secured in the Inflation Reduction Act—the funds that the new proposed budget now partially rescinds—to “restore fairness in tax compliance by shifting more attention onto high-income earners, partnerships, large corporations and promoters abusing the nation’s tax laws.”

While both of the above studies are unique in their ability to dive into the distributional effect of audits, there has long been strong, widespread evidence that cutting the IRS budget is penny-wise and pound-foolish—something even the official government scorekeepers acknowledge. In fact, the research strongly suggests that fully funding the IRS will likely generate even more revenue than official government estimates.

This year’s budget negotiation led to an accelerated cut, moving forward a $10 billion rescission that was already scheduled to go into effect in fiscal year 2025. Yet those who have made IRS cuts a hallmark of their economic policy platform are all but certain to call for additional cuts to fill the gap they have now created in the 2025 budget.

As the evidence above makes clear, further IRS cuts would undermine the government’s ability to restore fairness to our nation’s tax administration system and efficiently raise revenue. Congressional leaders—especially those who profess to care about the national debt—ignore this evidence at the country’s peril.