College football’s inequality dilemma amid the coronavirus recession

Before the coronavirus pandemic and the recession it caused, the economics of college sports, particularly college football, took a backseat to game-day coverage of tens of millions of fans spending freely on eating, drinking, and cheering in tightly packed stadiums and bars, tail-gate parties, and backyard barbeques across the United States. In particular, the economic well-being of the athletes themselves and the financial imperatives for the college and university towns and cities where these games are played was, by and large, overlooked by the majority of fans.

Now, however, even Americans with no interest in college sports are taking part in conversations about whether college football should be played this fall and, by extension, what the economic impact would be of deferring a year of sports. Two of the Power Five college football conferences, the Big 10 and Pac-12 conferences, decided earlier this month to suspend their fall seasons at least until January due to the still out-of-control coronavirus pandemic and COVID-19, the disease caused by the virus.

In contrast, the other three conferences—the Atlantic Coast Conference, the Big 12, and the Southeastern Conference—say, for now, that they will forge ahead with the slimmed-down game schedules even as most of the regions of the country in which they play are among the hardest hit by the coronavirus pandemic. While the National Collegiate Athletic Association has started to implement measures to lessen the spread of COVID-19, the NCAA has not canceled the football season.

Certainly, a predominant factor for the ACC, Big 12, and SEC in forging ahead with a football season is the revenue generated: According to Patrick Rishe, director of the sports business program at Washington University in St. Louis, the top 65 schools in the Power Five generated $4 billion in revenue from football in 2018. Yet the chances of a full season of college football for the ACC, Big 12, and SEC conferences are in the hands of a virus that infects people of color, including students of color, more than other students, which, in turn, infects these athletes’ classmates and their parents and grandparents. And lurking in the background of all of this is the longstanding call for student athletes to be recognized as a labor force entitled to a voice and workplace protections, among other job-quality standards.

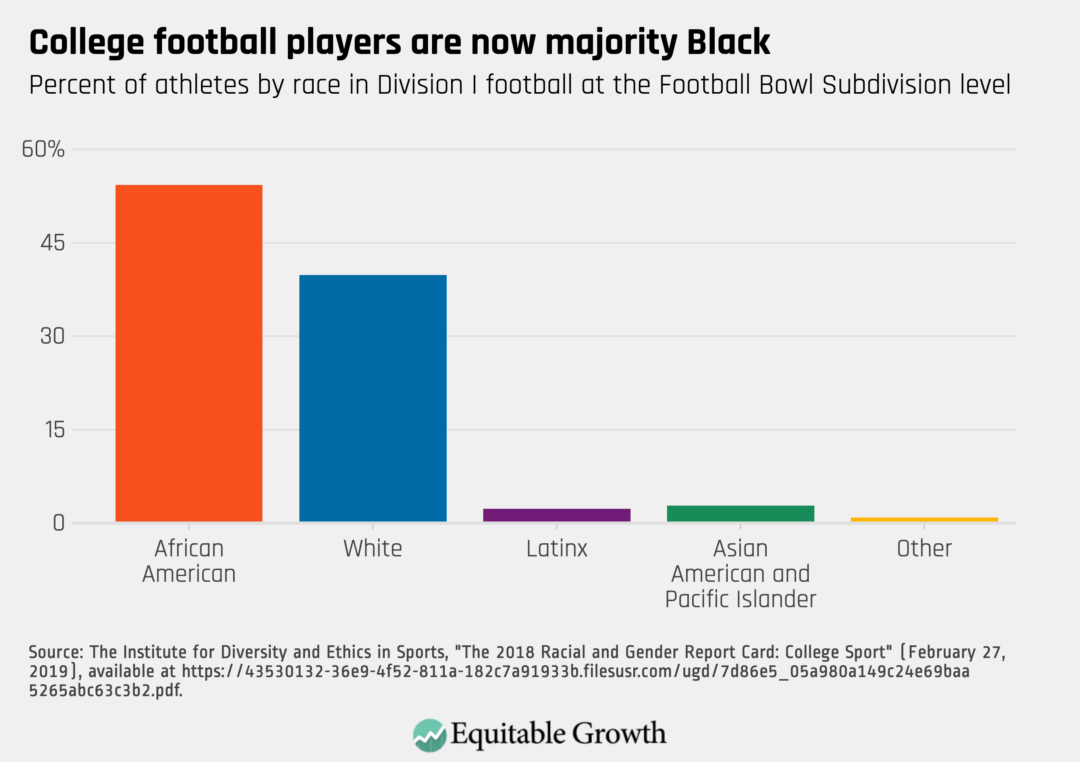

Of all student athletes in Division I football at the Football Bowl Subdivision level in 2018, 54.3 percent were African Americans, 39.8 percent were White, 2.3 percent were Latinx, Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders represented 2.8 percent, and 0.9 percent were classified as Other.

This higher infection rate and death rate among people of color in the United States is the defining health inequality of the coronavirus pandemic. Yet the pandemic and resulting recession also lay bare several economic inequalities that athletes of color have faced for decades, among them the lack of worker power enjoyed by their counterparts in the professional National Football League via their union, the NFL Players Association, as well as the massive subsidy these student football players provide to college and university sports programs and these institutions of higher learning overall. This difference is made more stark when examined through the lens of the race and ethnicity of college football players, who supported financially all other college sports programs in 2018—54 percent are Black, 40 percent are White, and 5 percent are Latinx and Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

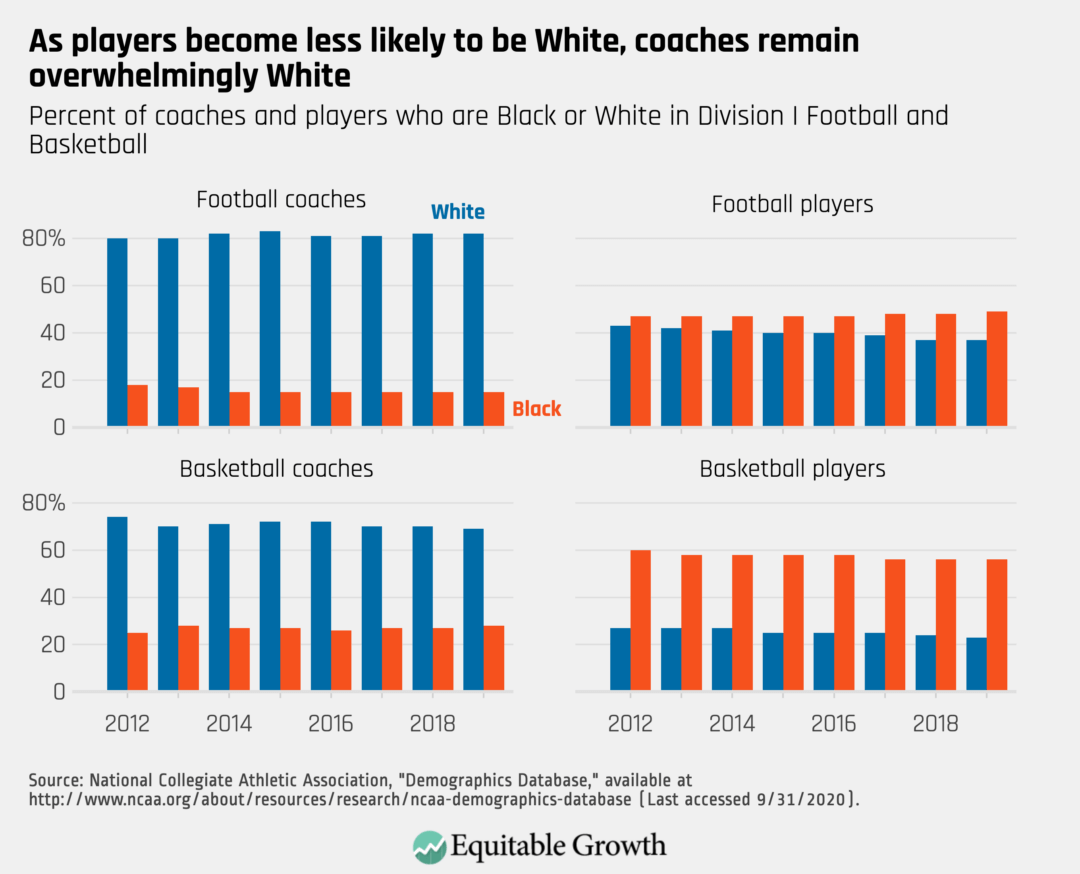

Compare this to the $1.2 billion in revenue just among the top five teams in the SEC, the ACC, and the Big 12 in 2018. That may seem like an apple-to-oranges comparison, except that the work of these majority players of color supports exceedingly well-paid head coaches in football and in the other college power sport, basketball, nearly all of them White, as well as all other sports programs. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

Here is just one telling case in point from SEC powerhouse Louisiana State University, ranked fourth in revenues in 2018, according to the SBNation/Vox News website Banner Society:

In 2018, LSU’s athletic department reported $145 million in revenue to the NCAA. Of that, LSU reported $87 million came from football. But that doesn’t tell the whole story. LSU also reported $39 million from media rights, the result of the SEC’s negotiations with ESPN and CBS. The athletic department only credited $12 million of that to football, even though anyone in college sports would tell you the vast majority of CBS’s interest in the SEC was football-based.

Football’s real contribution was well over $100 million of LSU’s $145 million in total athletic money. But even going by LSU’s accounting, football made $55 million in profit. Men’s basketball and baseball, together, added a little less than $1 million. Everything else lost money, but thanks to football, the department still made about $8 million.

Then, there’s the economic engine of college football in college and university towns across the nation. Like the restaurant industry, most Americans didn’t realize how important hospitality and leisure activities were to the economic well-being of their fellow citizens. The largely uncontrolled spread of the coronavirus in the spring and early summer made clear the economic importance of college sports in some of the towns and cities and rural communities in the South and Southeast, Midwest, and Mountain West that are most passionate about college football. Now, with the 2020 college football season over or seriously curtailed, business owners are facing heavy losses.

All of these data point to the economic importance of college football—especially to the importance of the players who are not paid to support this incredible economic edifice—and to the economic inequalities that are the sport’s very foundation. Seen in this light, the efforts by the SEC, ACC, and Big 12 conferences to play college football amid a pandemic that threatens players of color especially with possible career-ending sickness or even death before they ever get a shot at being paid as professional athletes means these conferences are ignoring longstanding health inequality along the lines of race and economic class on top of already egregious economic inequality.

This is the moment to come to grips with the intricacies of college football in our society amid the coronavirus recession and the enduring structural racism in our economy and society that underpins college football and also harms Black Americans and other Americans of color. College athletes are exploited while creating tremendous value during regular seasons, and their safety is put at further risk if they are to play during an uncontrolled pandemic. One way to address this problem may be the recently introduced “college athletes bill of rights” in the U.S. Senate by Sen. Cory Booker (D-NJ) and number of his colleagues. More immediately, a wise move could be for all conferences to pause this college football season because of the coronavirus pandemic and take the time to figure out how college sports, and college football in particular, could be more equitable and sustainable when the nation emerges from the coronavirus recession in 2021 or beyond.