Child care prices, inflation, and the end of federal pandemic-era aid in five charts

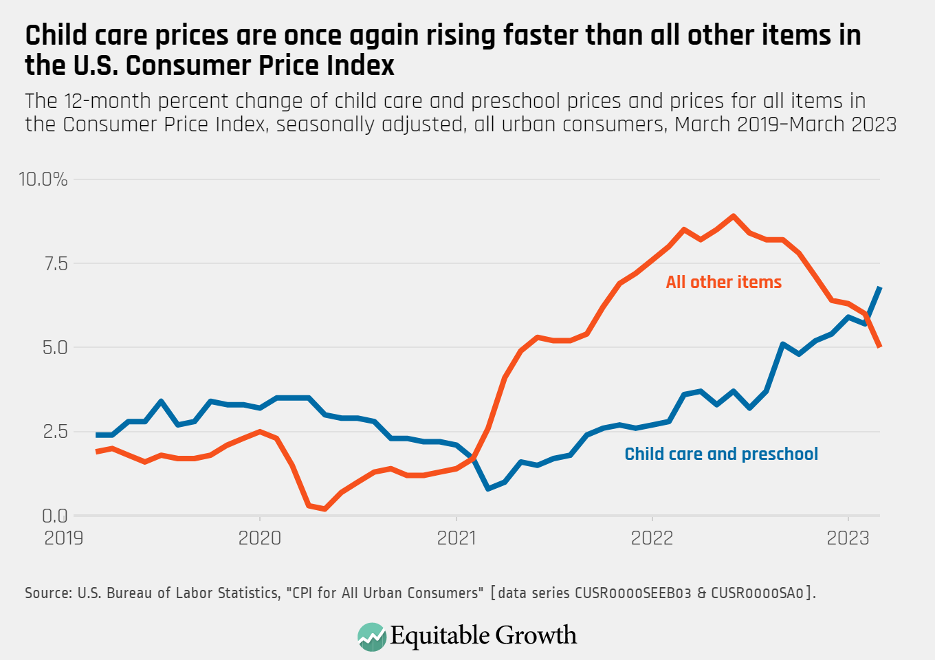

For much of the COVID-19 recession of 2020 and subsequent economic recovery, the child care sector was spared the accelerating inflation that impacted other areas of the U.S. economy. As prices for gas, timber, used automobiles, and other commodities rose, the cost of early care and education remained relatively steady, potentially due to softer demand and separation from the supply-chain struggles that plagued other sectors.

Throughout 2021, day care and preschool prices rose an average of 1.9 percent year-over-year, compared to 4.7 percent for all other items in the Consumer Price Index.

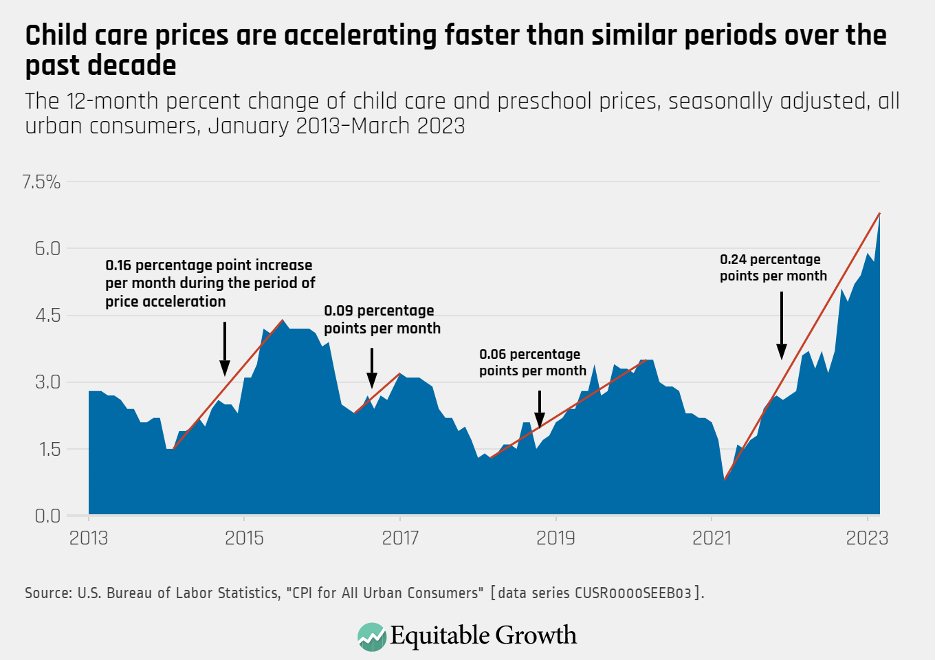

Today, the opposite is happening. As energy prices stabilize and supply chains un-kink, the cost of early care and education registered an annual increase of 6.8 percent in March 2023, the fastest in more than 30 years, while broader inflation cooled slightly to 5 percent year-over-year. (See Figures 1 and 2.)

Figure 1

Figure 2

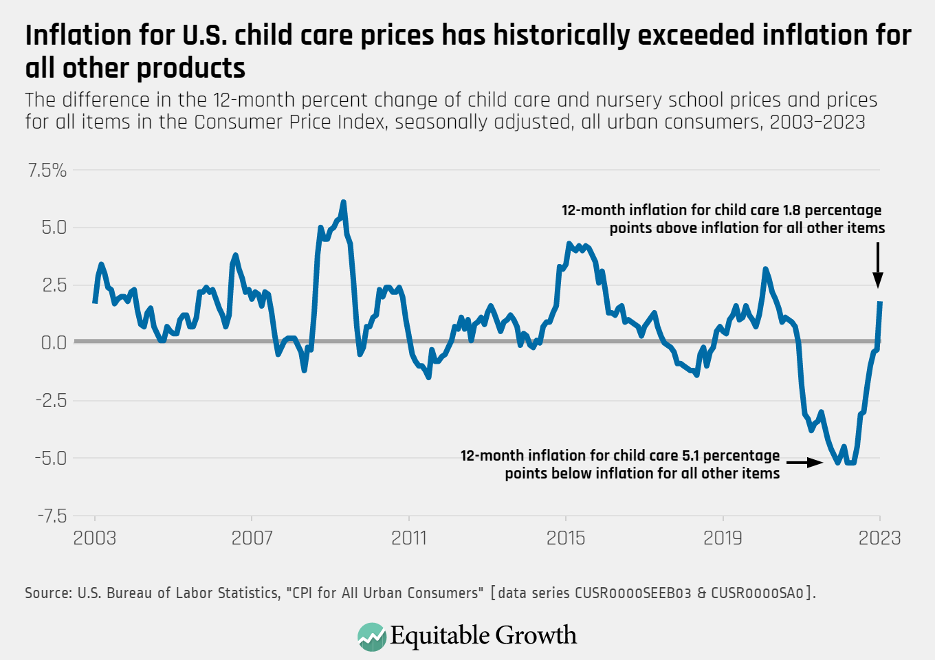

This is, in many ways, a return to the pre-pandemic status quo. Last year, Equitable Growth warned “that child care prices … are rising at a slower rate than the general Consumer Price Index should provide little comfort to policymakers and is not indicative of where child care prices are likely to go.” With the release of last month’s data, child care prices now have risen faster than broader inflation for 174 out of the past 240 months. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

Limited supply and child care’s labor-intensive business formula means that parents are always paying high prices even as workers and staff make relatively little. As high as child care prices are, they are in effect subsidized by low wages and low profits across the sector. Recent data suggests this dynamic is changing, with rising wages pushing prices higher just as pandemic-era aid to the child care sector is set to end.

High wages are a positive, long-overdue development in the child care market. But absent robust and sustained public investment supporting these wages, the financial interest of families and workers are pitted against one another, with one group’s access to care dependent on the indigency of the other.

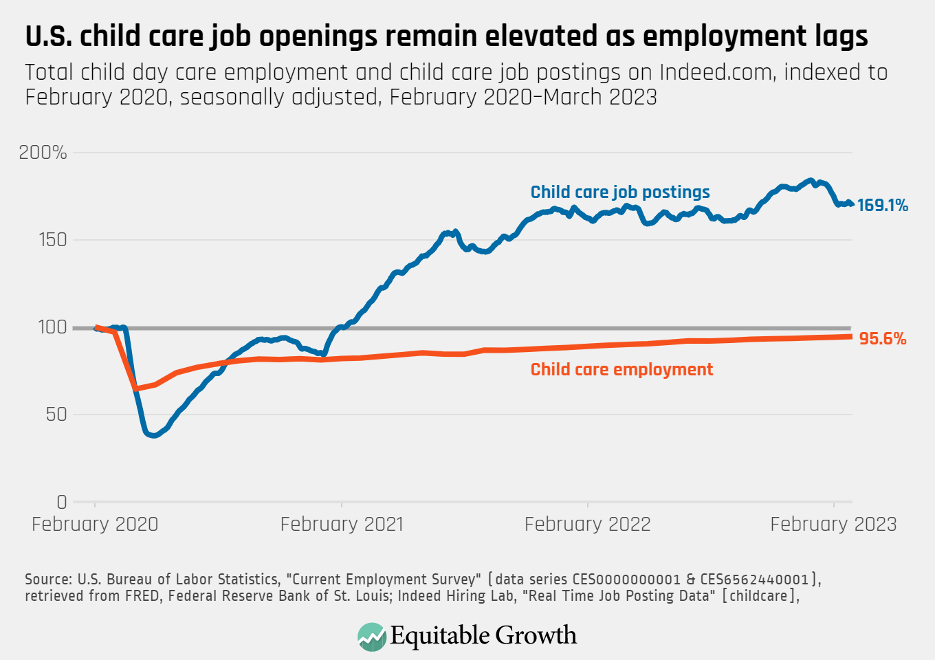

For decades child care workers have been undercompensated for the economic value they generate, earning some of the lowest wages in the U.S. labor market. Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, the low-wage, high-stress nature of the job contributed to persistent staffing shortages across the country.

Child care employment remains below pre-pandemic levels despite a full recovery in the broader U.S. labor market. Postings for child care jobs on Indeed.com, for example, are 169 percent of their pre-pandemic rate while actual child care employment is still down 4.4 percentage points (See Figure 4.)

Figure 4

This tightness in the child care labor market should be a recipe for rising wages as providers work to retain and recruit staff. This inevitably translates into higher prices for families. According to an analysis by the Center for American Progress, salaries and benefits account for 65 percent to 76 percent of providers’ costs. Without cash reserves, investments, or profits to cushion rising wage costs, child care providers must pass them on to the families they serve.

Also at play are billions of dollars in pandemic-era emergency relief intended to rescue the child care sector from the pandemic-related crisis. With the Consolidated Appropriates Act, 2021 and, more significantly, the American Rescue Plan, Congress allocated nearly $50 billion in emergency aid to the child care sector, which was on the brink of collapse.

Much of this funding was flexible, and states used it to bolster subsidies, attract new providers to the market, and increase compensation for child care workers, among other purposes. Early research suggests the funding may have kept tens of thousands of providers from shutting their doors, saving nearly 3 million child care slots.

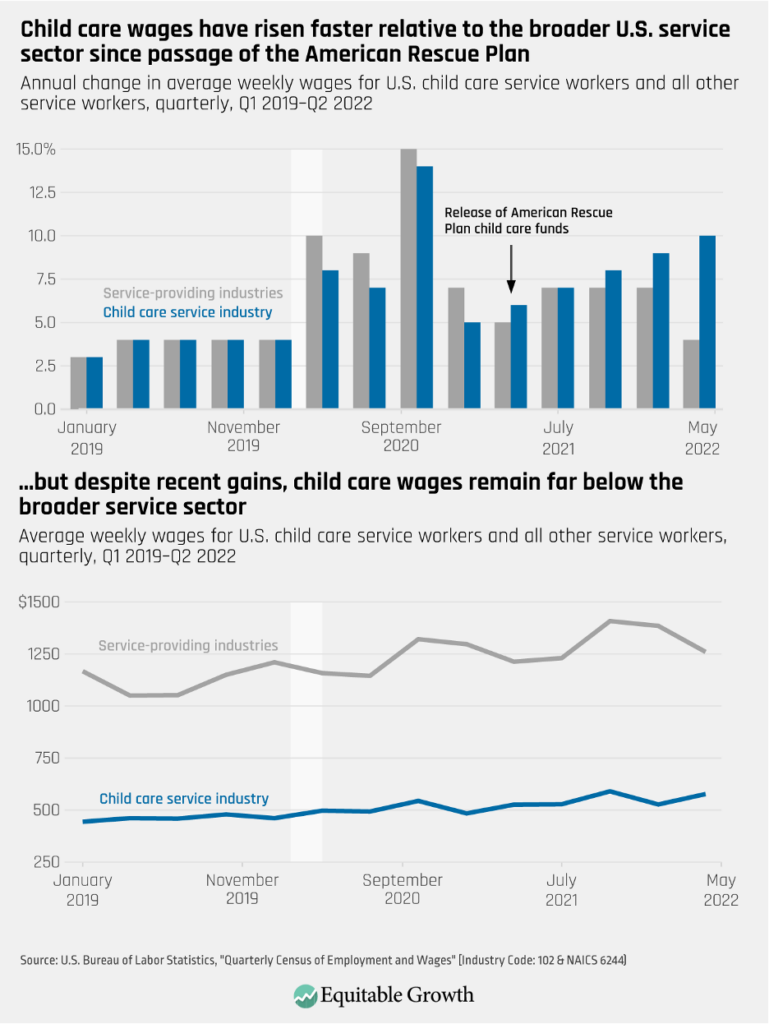

A big question stemming from the American Rescue Plan was whether this temporary infusion of funds could translate to sustained higher salaries for child care staff. According to data in the Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages available through the second quarter of 2022, child care wage growth has been accelerating since the implementation of the American Rescue Plan, even while growth in the broader service sector shows signs of stabilizing or even decelerating. More research is needed to determine how the American Rescue Plan specifically, relative to other labor market trends, has contributed to this increase. (See Figure 5.)

Figure 5

Of course, average child care wages remain far below those in the broader service sector despite this recent growth. This current dynamic may leave the child care market in an uncomfortable posture, particularly as expiring pandemic-era aid leaves families more exposed to these higher costs.

Increased wages for child care workers, even as they translate into higher prices for families, are essential for stabilizing—and, ideally, expanding—the supply of child care. But if rising wages remain below comparable sectors, then child care wages still may not be high enough to attract talent back and sufficiently expand supply, leaving providers and families with higher costs and limited public support for sustaining those costs.

Conclusion

Temporary public investment helped stabilize the child care industry, promoted more equitable wage compensation, and limited families’ child care costs through higher subsidies or direct payments to child care providers. Presently, wages appear to be rising, but perhaps not high enough to rapidly expand supply, and expiring pandemic-era child care aid means that families could lose out on those direct and indirect subsidies that helped keep care affordable.

Advancing research and evidence on child care and U.S. economic growth

November 10, 2022

I wrote in May 2022 that child care was facing three potential futures. In one future, child care wages stay low, supply is constrained, and families are saddled with higher costs in the form of increased prices, higher search-costs, and opportunity costs from forgone work for those unable to find care. In the second future, child care wages rise, stabilizing supply but directly raising child care prices. Only in the third future, one built on public investment, could wages rise, supply expand, and families remain sheltered from these costs.

Today, rising wages across the child care sector are a necessary and positive development. Higher compensation will attract new talent to the sector and stabilize the workforce, improving quality of care. But someone must pay for it, and families may be at their limit. Without ongoing public investment to bridge the gap between families’ budgets and the true cost of providing accessible and high-quality care, current growth in child care wages may prove transitory. Child care may emerge from the COVID-19 pandemic intact, but the opportunity to transform the child care market into a thriving, functioning sector will have passed us by.