Child care is essential for working parents, but is the industry ready and safe to reopen?

By now, it is no secret that parents across the United States are struggling. Adapting to life during the coronavirus pandemic has been difficult for nearly everyone, but parents—particularly those with young children—are facing day-in, day-out work-life conflicts with no end in sight. Whether they are continuing to work from home, unemployed, or still working outside the house, providing for their children without the support of schools, daycare, camps, or even help from grandparents is taking an emotional and economic toll. Rarely has the role of child care in supporting our economy, by freeing up parents’ time and minds to focus on work, been more self-evident.

For weeks, experts and parents alike have been warning that child care will be essential in any economic recovery from the coronavirus recession. Without it, many parents, particularly women, will have to weigh dropping out of the labor force or reducing their work hours if their caregiving responsibilities remain incompatible with their work responsibilities. Still, plans to reopen schools and child care facilities remain scattershot, largely driven by uncertainty about how coronavirus infections spread in such environments, how children may contract or spread the virus to adult staff, and how susceptible children themselves are to COVID-19, the disease spread by the coronavirus.

How to provide child care safely is primarily a question for scientists and public health experts, but policymakers and social science researchers have their own role to play in this ongoing crisis. First, the coronavirus pandemic must be treated as the workplace safety issue that it is. This involves developing a national set of safety standards—along with the appropriate education, training, and funding to enact those standards—so that parents and staff can be confident that their care is as safe as it can be. Without such standards, each facility will have to fend for itself with limited knowledge and potentially disastrous consequences.

Also important are policies designed to make child care accessible and affordable even in the midst of a pandemic. Recent research suggests that the child care market will be unprepared to provide care in a post-pandemic environment without significant public investment. If parents are shifting their preferences as a result of the pandemic and ensuing economic crisis—either by desiring smaller providers or working more nonstandard hours—then the policy challenges of providing high-quality and affordable care will only grow.

More research on what child care services families need and what the child care industry is poised to provide will help target the policy response supporting families as they return to work and fuel the economic recovery.

Child care priorities prior to the coronavirus pandemic limit our post-pandemic options

The United States does not have a universal child care system, so many families rely on a patchwork of polices, including tax credits, licensing standards, and subsidy programs, to access high-quality child care. These policies help some families afford much-needed care, but they are largely insufficient in meeting the variety of care options that families need. What’s more, these policies underpin a child care system that lacks the flexibility necessary to meet the shifting needs of families in response to the current pandemic.

As the coronavirus and COVID-19 continue to spread through communities, larger child care centers, where dozens of children are together in one building, may be more prone to spreading both the virus and the disease. Already, some communities are reporting alarming transmission of COVID-19 in child care centers, though some studies suggest the disease is less likely to spread among children.

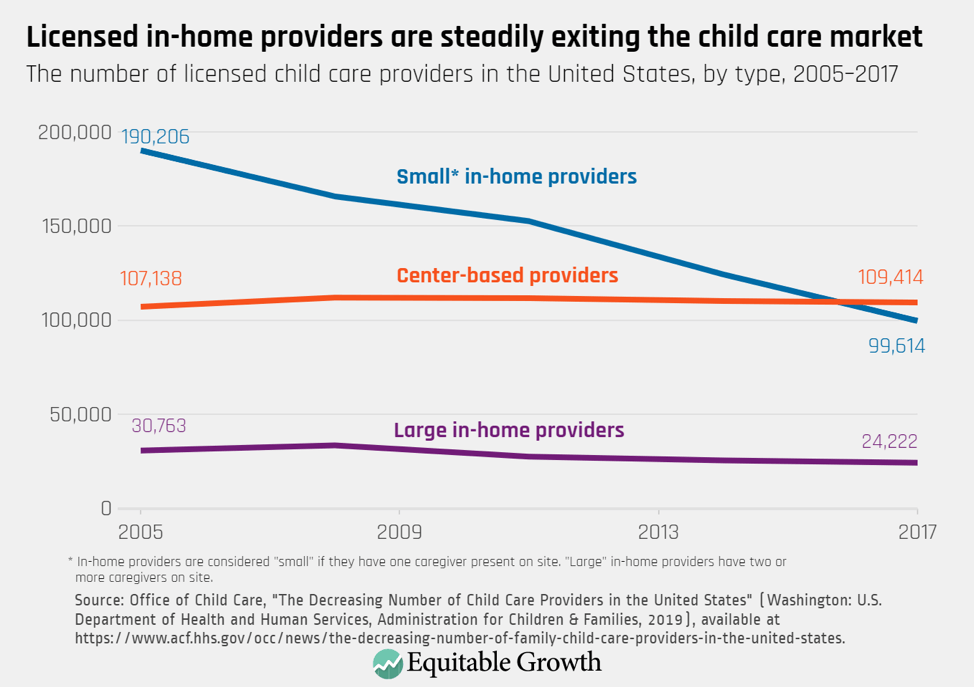

While wealthy families can hire nannies or babysitters to limit exposure, middle- and lower-incomes parents may be driven to seek in-home care. This type of care, also called home-based care, typically occurs in the provider’s home, where only a handful of children are present. It may be reasonable to assume these less-crowded settings are a safer alternative for families concerned about the safety of their kids and themselves. But the number of licensed in-home providers has rapidly declined over the past two decades. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

As some of these in-home providers exit the market, others may be transitioning to an “underground” market of unlicensed providers. These providers, which may be legally unlicensed depending on state statute, do not necessarily provide lower-quality care. But regulators cannot oversee the quality of care in these settings to the same extent that they can with those that are licensed. Parents who prefer in-home care over child care centers may be left with a difficult trade-off between accessibility of care and their confidence in a provider’s quality. Unfortunately, even parents who find an acceptable in-home provider could lose out on the subsidies that made their previous care arrangements affordable.

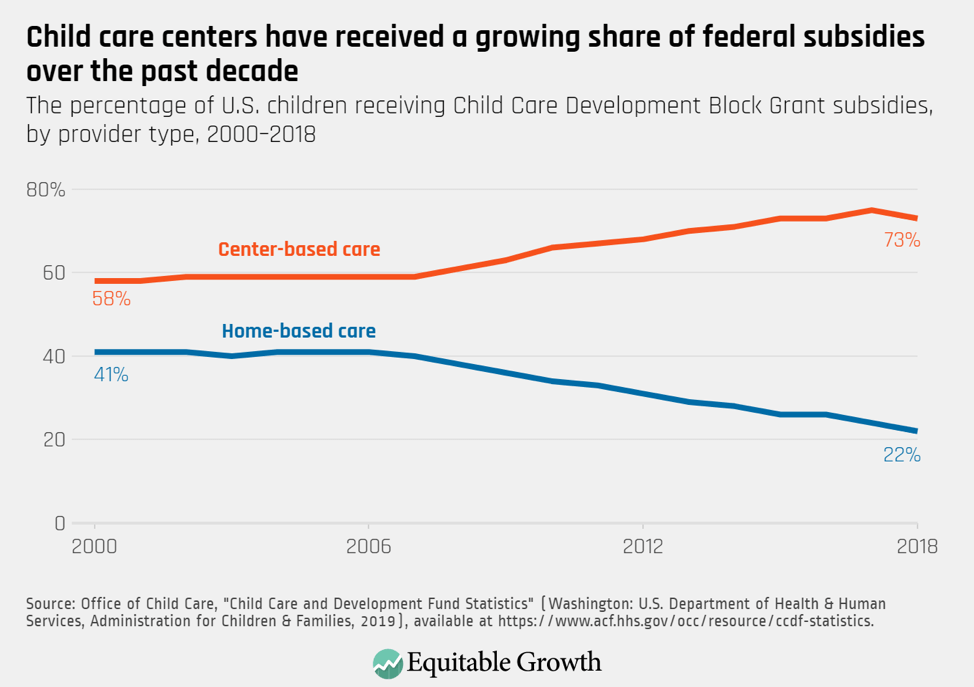

Child care can be incredibly expensive, even exceeding the cost of college in some states. Many families rely on some combination of tax credits or subsidies to help cover the cost. The Child Care Development Fund is the primary child care subsidy program for low-income families in the United States. When the program was reauthorized in 2014, it included important health and safety requirements for eligible child care providers but did not guarantee sufficient additional funds for states to enact these requirements. Experts say this has inadvertently advantaged child care centers, where states are better positioned to provide oversight and training.

Centers care for about 40 percent of preschoolers with a regular, nonrelative child care arrangement but serve more than 70 percent to 78 percent of similarly aged children receiving Child Care Development Fund subsidies. Conversely, in-home care serves 34 percent of similar preschoolers but around 18 percent to 25 percent of those receiving subsidies. This disparity in funding has dramatically widened in the previous decade. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

Reshifting subsidies toward these in-home providers is not a simple task. States will need to devote significant resources supporting in-home providers, particularly those that are exempt from licensing, to meet quality standards. Experts already worry that quality standards are too geared toward center-based providers and do not reflect the relative strengths and opportunities of in-home care. This could present an opportunity for high-level rethinking of what defines “quality” for these settings—a task for researchers as much as it is for regulators and policymakers.

Information on the spread of the coronavirus and COVID-19 and their effects on the economy changes rapidly. In the coming months, many families will be continuously reassessing their child care needs and what levels of risk are acceptable. The child care system, and the policies that help make it accessible to more families, must be flexible enough to meet parents’ needs without sacrificing quality or affordability. Unfortunately, these may be longer-term fixes in a system facing immediate shortfalls.

The supply of child care amid the pandemic is down, but parents are still searching for the care they need

These challenges in the U.S. child care market are longstanding, but they are now exacerbated by the coronavirus pandemic and COVID-19. More research is needed to understand how larger structural changes—such as additional subsidies or adjusted licensing standards—can be accomplished. In the meantime, the child care industry also faces an immediate critical shortage of providers who can care for the nation’s children once parents return to work.

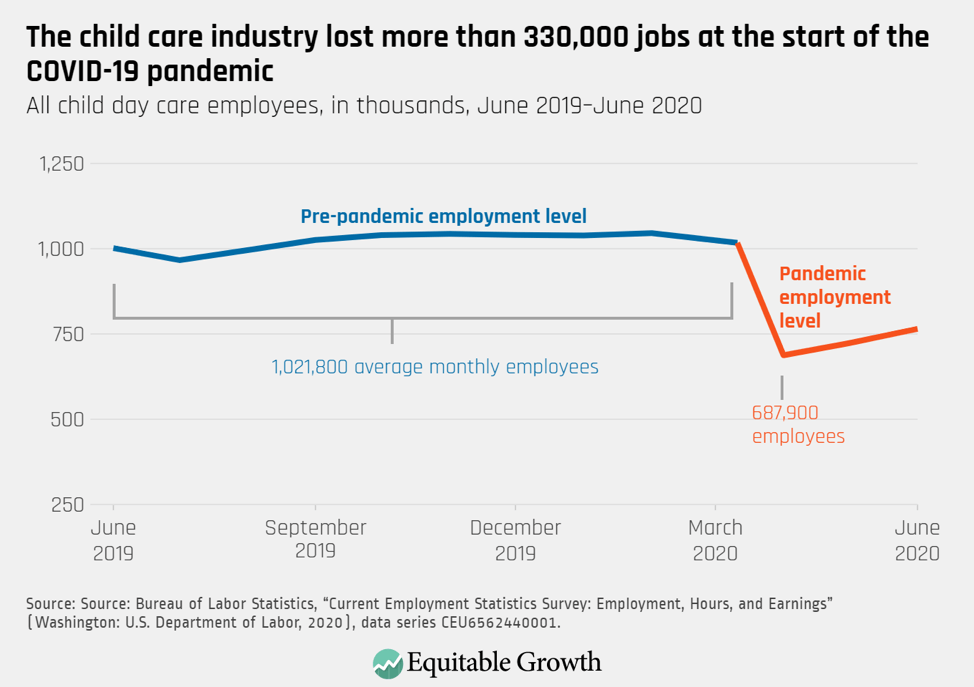

Like many industries, the coronavirus pandemic and resulting public health measures were shocks to the child care market. An April poll by the Bipartisan Policy Center found 60 percent of licensed providers shut their doors amid lockdowns and stay-at-home orders. More than 330,000 jobs were lost in the child care sector in only a few short weeks. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

The U.S. child care system was already in a pre-existing financial crisis, and the fallout from the pandemic could mean millions of child care slots are permanently lost. Affordable and accessible child care will be the foundation of any economic recovery, but right now, that foundation has multiples fractures.

In addition to layoffs, the industry dramatically slowed hiring in recent months. A new working paper by Umair Ali, Chris Herbst, and Christos Makridis, economists at Arizona State University, titled “The Impact of COVID-19 on the U.S. Child Care Market: Evidence from Stay-at-Home Orders,” finds that new online postings for early child care and education jobs declined 13 percent per dayfollowing the adoption of states’ stay-at-home orders, resulting in approximately 1,000 fewer providers hired per month than if the pandemic had not occurred. Assuming that these postings were to replace providers who exited the field and not providers who may be postponing a retirement or resignation during the pandemic, 1,000 fewer providers could mean as much as 10,000 fewer child care slots each month.

Even as the industry has been rattled by the coronavirus pandemic and recession, there is evidence that families remain interested in—or at least curious about—their child care options. The same working paper by the three researchers finds no statistically significant decline in Google searches for child care-related terms following state lockdowns. Of course, parents searching for online information on child care does not mean that they currently want or need those services. Many parents—63 percent in one survey—are skeptical about sending their children to child care while the coronavirus and COVID-19 are still spreading.

But just because many parents are not sending their children to child care now doesn’t mean they will not want to—or need to—soon. Even larger child care centers could face a critical capacity issue as parents return to work. Child care operates with low child-to-caregiver ratios, which means providers may need to hire quickly in order to ensure appropriate staffing for returning children. Encouragingly, child care job postings have rebounded by 23.4 percentage points since their lowest point in May, but they remain more than 39 percent below the postings in July 2019. And these recent gains may be tenuous as states resume partial shutdowns through the summer.

Sooner or later, many parents will have to make difficult decisions on when their children are going back into child care and what type of child care is best for their family. Without significant public investment—more than $9 billion a month, according to some estimates—the industry will be unable to provide the care necessary to help families get back to work.

Conclusion

The struggle facing parents today is not one they face alone—it boasts important implications for everyone affected by the coronavirus recession. Research shows that when child care is not accessible or affordable, it can prevent parents, particularly mothers, from entering the workforce. Policymakers and economists are already seeing signs that the lack of child care is creating a drag on women’s employment during the current crisis. Fewer working parents means a smaller tax base, reduced household income, and less money spent on goods and services—all the tools needed to help the economy recover.

As states decide whether to continue to ease their coronavirus restrictions or return to earlier lockdown levels, and as families decide whether to take cautious steps toward resuming their pre-pandemic lives, the demand for child care is only going to rise, particularly as schools and summer camps remain closed and public health experts caution against grandparent care. Policymakers need to take bold action to ensure that child care is accessible and affordable, and high-quality research must help target the policy response.

Most immediately, the industry needs an injection of cash to keep the doors open and caregivers on the payrolls. Many child care advocates have requested $50 billion in flexible funding in the next congressional coronavirus relief aid package. Looking further out, policymakers and researchers will need to turn their attention to the structural challenges discussed above that could limit parents’ options as they seek safe and affordable child care for their children. Otherwise, child care could remain out of reach for many families returning to work, and the economic recovery will stall before it even begins.