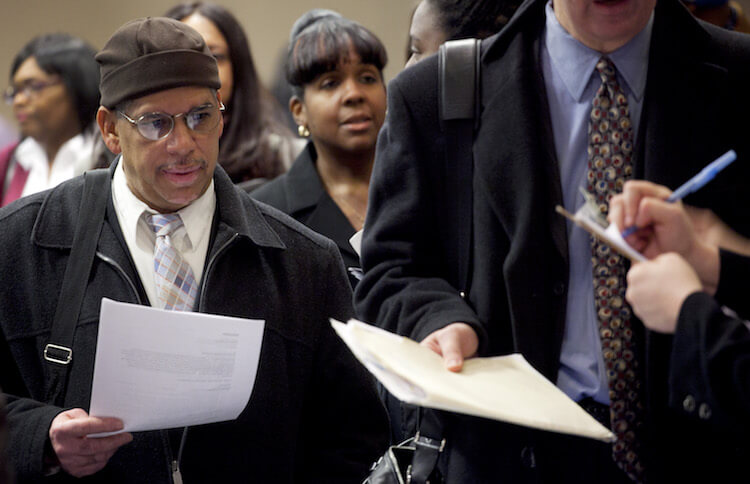

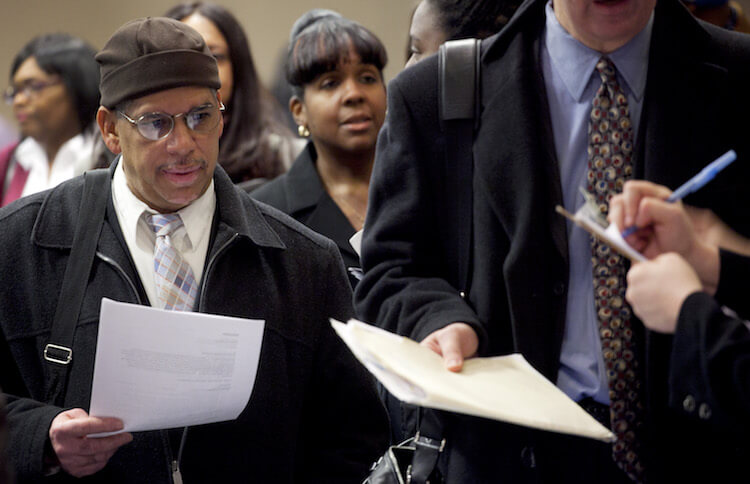

The U.S. labor market is a far less dynamic place than it was 30 years ago. Workers today are less likely to get a job while unemployed, move into unemployment, switch jobs, or move across state lines. You’d think just the opposite would be true given some of the discussion about our rapidly changing digital economy, but the data show what the data show. Even still, the reason—or reasons—for the decline in fluidity aren’t known.

A new working paper—by economists Raven Molloy, Christopher L. Smith, and Riccardo Trezzi of the Federal Reserve and Abigail Wozniak of the University of Notre Dame—takes a closer look at the decline in labor market fluidity and tries to find the causes. While the authors find nothing close to a smoking gun, they point to interesting avenues of future research.

The new paper, part of the Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, starts by laying out the trends in fluidity. Labor market fluidity can mean a number of things, including the rate at which workers move into and out of unemployment, switch jobs, and move across state lines. Molloy and her co-authors create a composite measure that combines these kinds of fluidities and find that overall fluidity in the U.S. labor market has fallen between 10 percent and 15 percent since the early 1980s. But for some of the individual flows, the decline has been as large as one-third.

Why has that happened? Let’s look first at demographics. The U.S. population has changed quite a bit since the early 1980s as more women have entered the labor market and the labor force has gotten older, among other trends. These demographic changes could be responsible for less fluidity as, for example, older workers are less likely to switch jobs. The authors find, however, that while demographics can explain a decent amount of the decline in fluidity, it can’t explain the “bulk of the decline.” A full accounting needs to look at other potential causes.

Molloy and her co-authors look at two groups of potential causes of the decline: benign causes and “less benign causes.” Because while the decline in movement within the labor market may seem troubling on its face, it’s not necessarily a bad thing. Declining fluidity might be a sign that workers are better matched with employers. Or perhaps workers don’t have to switch jobs as much as in the past because they can get larger raises by staying with their current firms. In other words, workers can climb the job ladder inside their current firm instead of jumping to a rung at another firm. The authors find no evidence, however, that the return to tenure has increased and that the gain from switching jobs has declined. But they do think much more investigation needs to be done in this area.

Another thought is that the rise of labor market regulations or other regulations in the economy might explain the decline in fluidity. But the economists cite research by Nathan Goldschlag and Alex Tabarrok of George Mason University that finds federal regulation has “little to no effect” on economic dynamism. Nor is there much evidence that land-use regulations have depressed across-state moves. While the authors do find some speculative evidence that declines in fluidity are related to declines in social trust, the results aren’t particularly strong, so much more research is needed on this particular question.

The authors acknowledge that the paper “has raised at least as many questions as it has answered,” but that’s not a bad thing. After their analysis, it seems more likely than not that the decline in labor market fluidity is harmful for U.S. workers. As such, spurring more research in this area is critical, because if we want to restore some fluidity, we need to figure out where the leak is.