The Productivity Puzzle: How Can We Speed Up the Growth of the Economy?

First, I need to stop flashing to the dystopian future which Bronwyn here has made me imagine. It is one in which drones overfly my house with chemical sensors constantly sniffing to see if I am cooking Kung Pao Pastrami–without having bought the required intellectual property license from Mission Chinese…

Deep breath…

Three big things have been going on with respect to productivity growth here in the United States over the past half century.

First came the productivity growth slowdown proper: If you had, forty-five years ago, asked a then appallingly young Martin Baily how prosperous the U.S. would be in 2025, he would then have bet that GDP per capita in 2025 would $125,000 in 2009-value dollars. The productivity slowdown that began after 1973 pushed that estimate down to $80,000 2009-value dollars of per capita GDP as of 2025. That is the forecast that Martin would have made–did make–throughout the 1980s and well into the 1990s.

Second came the information age growth spurt of 1995-2004: It looked like a return to the pre-1973 old normal in productivity growth driven by the technological revolution in information and communication technology. We hoped that it was a permanent shift. It turned out to be a one-time blip: first up, then down.

Third came 2008. After 2008, we are no longer expecting $80,000 of 2009-value dollars of per capita GDP in 2025. We are expecting only $63,000. This is a second big jump down, one very closely tied to what happened in 2008, and one of remarkably large magnitude given that come 2025 it will have had less than two decades to cumulate and compound.

These are three–four if you want to distinguish the bounce-up in 1995 from the bounce-down in 2004–different phenomena. They need to be analyzed separately and distinctly.

Consider 2008: We ought to have had a substantial recovery back to the pre-2008 trend after the 2008-2009 crisis. We did not. (Bob Barro will talk a bunch about that anomalous surprise later on.) I merely want to stress now that our failure to see a true and proper recovery back toward if not to the pre-financial crisis trend is not because our economy has become sclerotic. It is not because the economy has lost its ability to reallocate resources to more productive uses as a result of market price signals. Consider the period 2005-2008. The economy reallocated resources fine from 2005-2008 away from housing and into exports, investment, and other categories. It did so financial markets changed their views of the housing sector. As their views of the housing sector changed, they sent different price signals to the real economy. And businesses responded to incentives on a truly remarkable and massive level in an astonishingly smooth way. Housing construction sat down. Business investment and exports stood up. And it all happened without a recession.

Then with what happened in 2008 came the big problem. The financial crisis created a low-pressure high-unemployment economy. After 2008 we hit the zero lower bound on interest rates. Optimism about how effective Federal Reserve quantitative easing and forward guidance polices could be turned out to be wrong.

Then we hit the economy on the head with the fiscal-austerity brick—mostly at the state and local level, but at the federal level as well. We hit it on the head over and over again. With interest rates at zero, the Federal Reserve finds no way to signal exports and business investment that they really should be doing more, and should be taking up the slack from fiscal austerity that was caused by hitting the economy on the head with the fiscal-austerity brick over and over again.

Moreover, we did nothing to restructure housing finance to assist peoples cared and panicked after the housing crash and living in their sisters’ basements from forming households of their own, and moving out.

And productivity growth collapsed and has stayed collapsed.

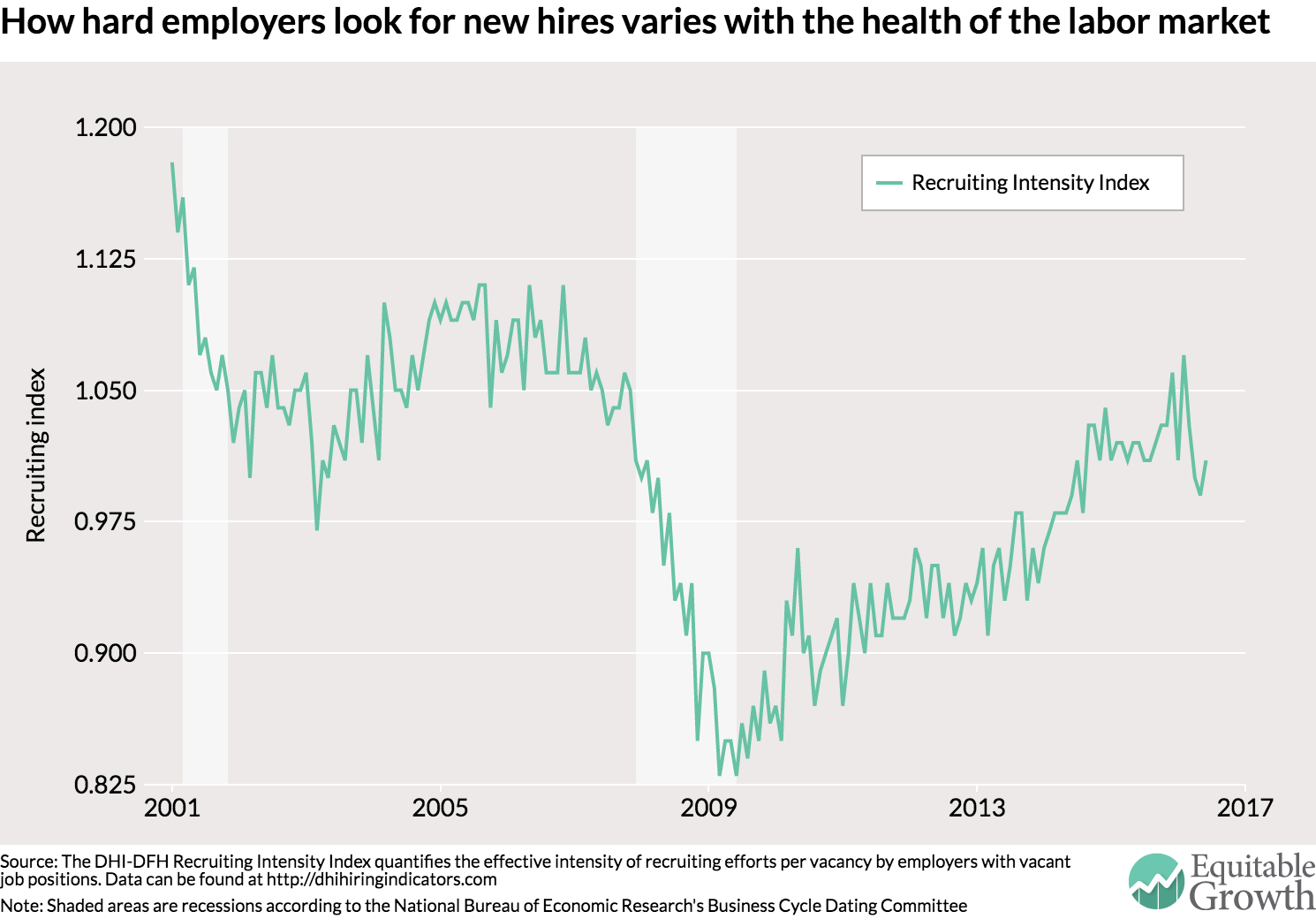

Why? I find myself very impressed with analyses like those of Steve Davis and Till von Wächter, of Gabe Chodorow-Reich and Johannes Weiland, and of many others. They say that it really matters for the process of creative destruction and reallocation whether it takes places in a high- or a low-pressure economy. Caught up in a mass layoff–something that is clearly in no way a signal of your skill level, productivity, or work ethic–when unemployment is low? You lose maybe 5% of your income over the next 20 years. Caught up in a mass layoff when unemployment is high? Your loss is more like 20% of your income over the next 20 years. “Employment flexibility” has very different consequences for long-run productivity growth depending on whether that flexibility leads you to move to a higher-productivity job or to unemployment or out of the labor force altogether. These macro-micro linkages are very clear in the labor literature. They seem barely noticed in the productivity literature.

Can we still recover from this post-2008 disaster?

First, I think we need to stop calling it the “Great Recession”. It will soon be the “Longer Depression”–longer than the Great Depression. It already is in Europe. Can we recover?:

- Back in 2009 I would have said: yes, we will recover easily

- Right here in 2012 Larry Summers and I said we could recover straightforwardly–but only with the right policies.

- Now? There are still people like Gerry Friedman who are very optimistic, who say that we could, and that it would be if not easy at least straightforward. I am not arguing with Gerry Friedman until November 15th. I will argue with him then.

Aside from striving for a high-pressure economy and hoping that Gerry Friedman is right–which Martin did recommend–what can we do?

There is no reason why reversing the poorly-understood factors that generated the first 1973 slowdown and that turned 1995-2004 into a temporary blip rather than a permanent shift should be the highest priority when we seek for policies to boost productivity. We should, instead, look for low-hanging fruit. What is the low-hanging fruit here?

I would focus on our value-subtracting industries:

- In finance we now pay some 8% of GDP—2% of asset value per year on an asset base equal to 4 times annual GDP. We used to 3% of GDP —1% and change of asset value a year for assets equal to 2.5 annual GDP. It does not seem to me that our corporate control or our allocation of investment is any better now than it was then. Certainly people now are trading against themselves more, and thus exerting a lot more price pressure against themselves. They are making the princes of Wall Street rich. Is there any increase in properly-measured real useful financial services that we are buying for this extra 5% of GDP? Paul Volcker does not think so. And I agree.

-

In health care administration we now pay another excess 5% of GDP. Our doctors, nurses, and pharmacists do wonderful things. But as Princeton’s Uwe Reinhart likes to say, you do the accounting and our health care administrators are about one-eighth as productive as German administrators. Why? Because they’re all working against each other. Half are trying to get insurance companies to pay bills. The other half are trying to find reasons why this particular set of bills should not be paid by the insurance company. Do any of you understand your health insurance EOB—Explanations of Benefits? If so, I congratulate you! Or, rather, I do not congratulate you: I there’s something psychologically wrong with you if you do understand them.

-

Mass incarceration—add up the effects on human capital and find another 2% of GDP that other countries do not pay that we are spending for, as best as I can see, no net value whatsoever.

-

The bet that we have made over and over again over the past 35 years that what the economy really needs is lower taxes on the rich. Elite conspicuous consumption is, by definition, not a source of social welfare–it is utility for the rich extracted by spite from the rest. It shows up in GDP as a plus. It does not show up as a plus in any even half-plausible societal well-being calculation.

-

NIMBYism. At this conference we have talked a little bit about occupational NIMBYism. It may be a big factor—I am not convinced, but I also am not unconvinced. But there is more. As Bronwyn said yesterday, anyone who lives in San Francisco or D.C. or Boston has got to be very impressed with residential and land-use NIMBYism as a major factor. But our judgment that land-use NIMBYism is an important factor may just be the myopia of where we Route 128 and Silicon Valley people have to live.

In my remaining time, I wish to echo what Bronwyn was saying: We need to more attention to the government’s regulation and management of research and development. We have a world that is increasingly non-Smithian, in terms of what we make and where value comes from. Yet our government seems increasingly confined to four roles: a military, a social insurance company, a protector of property rights—especially of stringent and quite probably counterproductive at the margin intellectual property rights—and an enforcer of contracts. It seems, increasingly, on autopilot with respect to other things. That cannot be healthy at all.

INTERRUPTION: “You didn’t use the words ‘public investment’ once.”

I thought you would. (Laughter)

I did include an allusion to Larry Summers’s and my paper that we gave in this space back in 2012. I hereby incorporate that entire paper by reference in my revised and extended remarks.

Extra Slides: