Brad DeLong: Worthy reads on equitable growth, April 12–18, 2019

Worthy reads from Equitable Growth:

- From 1.5 years ago, a primer on what tax distribution tables are good for, from Greg Leiserson, “If U.S. tax reform delivers equitable growth, a distribution table will show it,” in which he writes: “Distribution tables—estimates of who wins and who loses from changes in tax law—are central to any debate about tax reform. Such analyses frequently show the plans put forward by Republican politicians to be severely regressive, delivering large income gains for high-income families and little for the overwhelming majority of families. The blueprint for tax reform released by House Republicans in 2016, for example, would increase after-tax incomes for the top 1 percent of families by 13 percent in the first year after enactment but would increase incomes for the bottom 95 percent of families by less than half of 1 percent.”

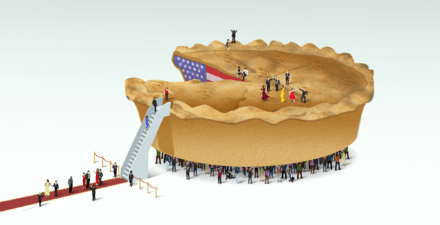

- Policymakers and economists do not really know how they would collect and enforce a net-worth tax—but we did not really know how we would collect and enforce a broad income tax either until Milton Friedman came up with payroll withholding. In some ways, the administrative burdens of a net-worth tax will be a lot easier since it is designed to catch only the upper tail. Read Greg Leiserson, Will McGrew, and Raksha Kopparam’s “Net worth taxes: What they are and how they work,” in which they write: “The wealthiest 1 percent of households owns about 40 percent of all wealth … Taxes on wealth are a natural policy instrument to address wealth inequality and could raise substantial revenue, while shoring up structural weaknesses in the current income tax system.”

- Remember: The Trump-McConnell-Ryan tax cut did absolutely nothing to boost investment in America, and thus has no supply-side positive effects on economic growth. And it is another upward jump in inequality. Read Greg Leiserson’s slide show, “U.S. Inequality and Recent Tax Changes,” in which Leiserson argues that the recently enacted Tax Cuts and Jobs Act will likely increase disparities in economic well-being, after-tax income, and pretax income.

- Three worthy reads on taxes after April 15 is enough. Let’s switch to another topic. One of the larger and more encouraging reviews of assessments of early-childhood interventions is Will McGrew’s “Investments in early childhood education improve outcomes for program participants—and perhaps other children too.”

Worthy reads not from Equitable Growth:

- It is power and surveillance rather than worker displacement that is the principal issue on the table with respect to automation for the next decade, and probably for the next two decades. Read Brishen Rogers, “Beyond Automation: The Law & Political Economy of Workplace Technological Change,” in which he writes: “Automation is not a major threat to workers today, and it will not likely be a major threat anytime soon. Companies are, however, using new information technologies to exercise power over workers in other ways … using algorithms to monitor, direct, or schedule workers, in the process reducing workers’ wages or autonomy. Companies are also using new technologies to “fissure” employment … If the major threat facing workers is employer domination rather than job loss, then exotic reforms such as a universal basic income are less urgent.”

- It’s not “the market or the state.” Rather, it is almost always “the market and the state.” A state that can enforce property rights is highly likely to be able to do a lot more useful things. A state that cannot do many useful things—one that is incompetent or corrupt—is highly likely to be unable to enforce the property rights that underpin markets either. Read Timothy Besley and Torsten Persson, “The Origins of State Capacity: Property Rights, Taxation, and Politics,” in which they write: “Legal and fiscal capacity are typically complements … Common interest public goods, such as fighting external wars, as well as political stability and inclusive political institutions, are conducive to building state capacity of both forms. Our preliminary empirical results uncover a number of correlations in cross-country data which are consistent with the theory.”

- Being poor—and, more so, being poorer than you had expected you would be and having to retrench—stresses you out and makes you unhappy. David G. Blanchflower and Andrew E. Clark decompose the children-make-you-unhappy fact in Europe into a “poverty” and an “other” component, and what they report makes a lot of sense: Children in a well-functioning family setting are a source of profound happiness, and poverty in particular and stress in general are sources of profound unhappiness. Read David G. Blanchflower and Andrew E. Clark, “Children, Unhappiness and Family Finances: Evidence from One Million Europeans,” in which they write: “The common finding of a zero or negative correlation between the presence of children and parental well-being continues to generate research interest … One million observations on Europeans from 10 years of Eurobarometer surveys … Children are expensive, and controlling for financial difficulties turns almost all of our estimated child coefficients positive … Marital status matters. Kids do not raise happiness for singles, the divorced, separated, or widowed.”

- Read the latest from Jared Bernstein at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities: “Ch-ch-ch-changes!” He writes: “GS fiscal analyst Alec Phillips … [is] worth a close look … One of the more important policy-driven determinants of near-term U.S. growth is under debate right now: setting discretionary spending levels for 2020/21 … Even were Congress to agree to keep the levels of discretionary spending stable over the next few years, the impact will be a fading of fiscal stimulus on real GDP growth … When it comes to fiscal impulse, it’s not the level that matters. It’s the change. The last deal—the one that determined spending in 2018/19—went both well above the caps but, more important from an impulse perspective, went well above prior agreements … That’s one reason to expect 2020 growth to be closer to 2 percent than 3 percent.