Analogies for AI policymaking

Overview

As a suite of technologies under the label of artificial intelligence increasingly take center stage, policymakers recognize the need to develop deep technical expertise about the deployment of evolving technologies in distinct contexts. But specific technical knowledge in the hands of a few will remain insufficient. All policymakers need to develop intuitions and an arsenal of heuristics to make decisions about automated systems across policy domains.

In this policy brief, we offer a series of analogies as a shorthand for policymakers who inevitably will need a range of short-term responses to AI and related automated systems. In doing so, we also emphasize that AI is more than just large language models; it includes smaller, simpler models that impact the public every day and systems that make use of AI as one of numerous components. These analogies are no substitute for an extensive understanding of specific tools and deployment contexts, but they offer an initial set of mental models to avoid over-heated first reactions based on hype or skepticism.

Analogies have developed a bad reputation in tech policy as it can be tricky to thread the needle of simplifying a complicated topic. They can make a policymaker or politician look woefully ill-informed, as was the case when Sen. Ted Stevens (R-AK) referred to the Internet as “a series of tubes” in 2006 and was widely ridiculed as being out-of-touch.1 This analogy, however, can be quite helpful. There are cables in tubes that form the physical backbone of the Internet. 2 Paying attention to the literal tubes matters enormously for infrastructure investment (to build more tubes) and for national security (to recognize who has jurisdiction over the tubes), but can be misleading when thinking in terms of content moderation (how does information actually flow?) or privacy (how is information appropriately safeguarded?).

Analogies remain central to policymaking. 3 The law relies on comparisons between websites and libraries or the public square, for example, while politicians may liken the internet to the highway system. 4 Over-indexing to one analogy is misleading, but so too is avoiding explicit frameworks.

Before diving into specific analogies, one stands out as particularly misleading. While we encourage a plurality of mental models, the most common analogy for AI has proven particularly detrimental: that a computer system is like human intelligence. The category of “intelligence,” and the associated metaphor that computers can “learn,” may have proven to be a generative research question in the lab, leading researchers aiming to create an intelligent machine to target logic and games (such as chess) and the capability of answering questions about generalized knowledge (as ChatGPT does), each time moving forward on the technical problems of AI.

Time and time again, however, the concept of intelligence is conflated with humanness, relegating some humans to a status of less than human. In practice, narrow definitions of “intelligence” have repeatedly aligned with or reinforced misogynistic and racist hierarchies. 5 Such definitions privilege some types of work and thus lead to the devaluing and automation of service and care work. 6 At its worst, discussions of “artificial general intelligence” have given a new framework and seemingly more palatable language to the dangerous ideas that human value is easily measured and assessed.

Artificial intelligence tools may pantomime human behavior, but evaluating them primarily on the uncertain yardstick of intelligence misses what the tools actually can do. The metaphor of intelligence encourages users to ignore the specific contexts in which AI is constructed and therefore capable of being effective. The headline-grabbing concept of intelligence has proven both normatively and descriptively dangerous when it leads to AI being both misused and misunderstood.

So, let’s turn now to some useful analogies for AI.

AI is like a hammer

Artificial intelligence is applied across many different domains, from tenant screening and cancer detection to content promotion and text generation. How can the same types of systems be used in so many different ways? Computer scientists use abstraction to translate problems in the real world into basic reusable computational forms. In the case of AI, this approach can allow information about people—including their background, health information, finances, demographic information, and more—as well as content, text, images, or other things in the world to be represented as data.

It is worth pausing on this initial step of essentially trying to put all relevant information into a big spreadsheet where all the context—the people, health information, meaningful content, or other reality—is abstracted away. Everything will look commensurable. AI systems are now like a hammer that can be applied to any data to make predictions, recommendations, or generate content. This is the impressive power of AI.

Yet abstracting away reality comes with real world risks. 7 Any data not represented correctly or fully in the spreadsheet will be misunderstood by AI, and AI can be applied in settings or based on data where the results don’t make sense. For better or worse, people are likely to apply AI across many domains. We fear AI is a powerful hammer, even when not everything is a nail.

AI is like the math you already know

Even policymakers who do not work with complex statistical assessments or econometric models have developed intuitions for the basic mathematical concepts. Relying on foundational mathematical frameworks offers a placeholder for the more elaborate work of AI-based systems.

AI is like a line of best fit

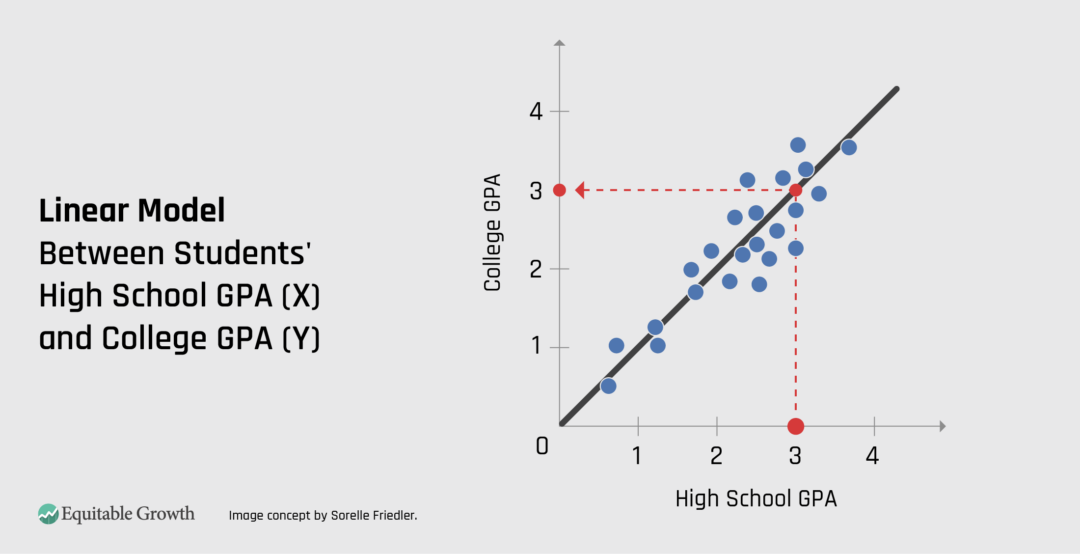

It may seem elementary, but one useful placeholder for the complex mathematics behind AI systems is the line of best fit, or trend line, from high school mathematics. Just as a line of best fit can be used to model a linear relationship between variables X and Y, AI systems aim to model relationships between variables and make predictions based on collected data—even when you could come to misguided conclusions based on those correlations.

Suppose, for example, that one used a line of best fit to create a linear model (function) between data collected about students’ high school Grade Point Average (X) and college GPA (Y). Given a new student’s high school GPA, we could use the linear model to predict their college GPA. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

Of course that prediction might be wrong, and AI models generally include more variables to help improve the predictions; they take more than one input and make predictions based on patterns that are more complex than a line. In practice, these lines of best fit are made from the idiosyncratic collection of incomplete and potentially incorrect data available, which of course may not fully capture the phenomena of interest. As the saying goes, “garbage in, garbage out.”

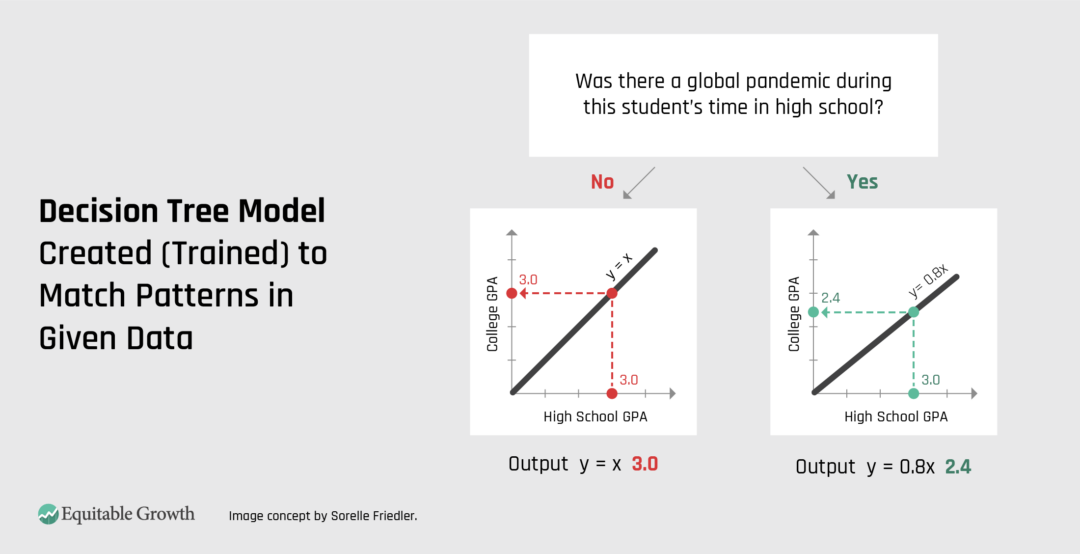

AI is like a big flowchart

One example of a more complex AI system is a decision tree. These are a form of flowcharts that can be created (trained) to match patterns in given data. Just like flowcharts, decision trees can take inputs of various types and make branching decisions based on the data. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

So, when looking at high school and college GPA data, along with other information about students, we might find that contextual information—such as whether there was a global pandemic while they were in high school—is useful in predicting a student’s college GPA. Maybe the first part of the flowchart checks whether there was a pandemic, and if “yes,” the flowchart points to one box while “no” points to a different next step in the process. The resulting output could still predict a student’s college GPA.

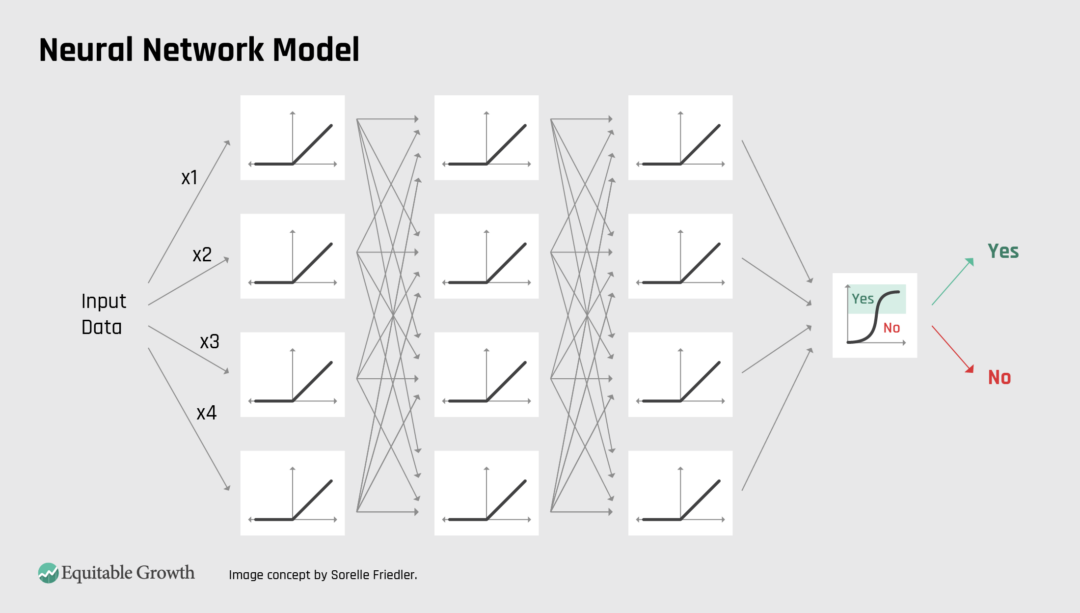

Neural networks that power many of the largest and currently best performing AI systems can also be thought of most easily as giant flowcharts. In neural networks, instead of a simple yes or no question in each box of the flowchart, there’s a mathematical function (such as a line of best fit) that provides an output value that’s sent to the next box of the flowchart as input. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

The complexity of neural networks comes from their size (flowcharts with billions of boxes and arrows) and because it’s hard to determine the right architecture (what boxes the flowchart needs and how it should be connected) and the right weights (how output values are scaled before being used as input into the next flowchart box). But after these choices are set, neural networks are really just big flowcharts that lead a given input through a series of mathematical expressions on the way to an output value.

AI is like a frequency table

When we think of modern AI, we often think of large language models, even though AI technology is much more general than these LLMs. In fact, all types of AI are built on the same basic mathematical ideas, from simple decision systems to more complex neural networks used for generative AI. But when considering LLMs, it’s useful to use one more mathematical analogy: the frequency table.

Frequency tables are just counts. For example, we might count the number of times each word appears in this paragraph (“word” appears 7 times). We could turn these counts into estimated probabilities that the word “word” appears by dividing by the number of total words (“word” would be 7/115). We could then use these probabilities to guess what word comes next; simply guess the word with the highest probability (or highest count in the frequency table). Of course, this won’t make great predictions. But if we counted multiple words in a row—phrases and sentences in this article, instead of words in this paragraph—then we’d get closer to something that looked like natural language.

If we expanded this example to all the text available on the internet we could get our hands on, as current LLMs do, then these predictions would become much more convincing. Still, it’s important to remember that what’s going on behind the scenes can simply be thought of as counting phrases and generating the most likely next phrase as output.

AI is like a curved mirror on society

AI is like a curved mirror in that it reflects the data it is given, even though it doesn’t exactly replicate that data.8 As we saw with the line of best fit and other mathematical analogies, AI is trained using pattern-matching schemes that then predict outcomes to replicate those patterns. It will take data and replicate patterns to determine whether the inputs are correct, whether the pattern makes sense, or whether the replication of that historical data and pattern is desired. When used in societal contexts, especially to assist in decision-making about people (think of the analogy above of AI’s use as a hammer), it can lead to inappropriate or even disastrous consequences.

AI is like redlining

Across sectors, it has become clear that AI systems are like redlining; they make decisions directly or indirectly based on protected characteristics, including race, and in practice further segregate people and solidify discrimination across multiple types of discrimination. AI systems are used to evaluate home buyers for mortgage approval and have been more likely to lead to a rejection of Black applicants than White applicants with similar financial standings, despite years of claims by financial institutions that the use of algorithms to screen applicants will lead to less discriminatory outcomes. 9

Similarly, hiring screening tools were found to inappropriately penalize women software engineers.10 Health care risk assessment tools were found to incorrectly mark Black patients at lower risk and less need of help. 11 And automated test proctoring and AI cheating detector systems were found to incorrectly identify disabled and international students as cheaters. 12

Understanding that AI systems are like a line of best fit, finding and replicating patterns in the given data, helps to make sense of these trends. Most software engineers have been men, so attempts by an AI system to replicate previous hiring patterns will lead to discrimination against women. Black patients historically have had less money spent on their care, so the use of the amount spent by a hospital to predict future risk will continue to treat Black patients poorly. And AI systems deal poorly with outliers, so students with disabilities and international students who don’t match the visual or linguistic patterns on which an AI cheating detector was trained will be incorrectly flagged as cheaters.

AI is like the Web remixed

When we consider generative AI—chatbots, image generators, voice synthesizers, and the like—it can seem uncanny how well some modern systems work. Yet these generative AI tools also are relying on the same mathematical underpinnings, engineered into a big neural network (flowchart). The trick is that they use a lot of data, remixed via AI to match your desired request. These systems can’t generate content entirely unlike any they’ve seen before, but with enough data remixed, the content can seem new. Unfortunately, a lot of content on the web is violent, racist, sexual, or otherwise undesired in many contexts. Without care, AI systems trained on such content will generate more of it.

It’s hard to conceive of the full extent of the data used to train these large AI systems; it is essentially as much online data as the companies creating the systems could collect. The data includes text from publicly accessible websites, transcriptions of YouTube videos, text from books, social media images and videos, and essentially anything that is available on the open or closed web. 13

Unlike the social media era, it’s not obvious that the walled gardens of the Big Tech online platforms will represent a critical advantage. What is needed is a willingness to bend the rules to get access to large data and the semiconductor chips and money to train these models. 14 Big AI systems now use trillions of words and are projected to cost trillions of dollars for training in the near future, with much of that cost going to buy specialized chips and to pay for the cost of data centers running for months to train a single model.

AI is like a factory that raises labor, infrastructure, and energy concerns

AI systems will lead to dramatic changes in labor force participation, the nature of work, and the workplace. Technical improvements alone do not drive these changes, but instead, novel technologies provide organizations with an opportunity to restructure work, as has been the case throughout history with the introduction of new technologies to the workplace. 15

Projecting what these changes will bring in terms of job loss or changes to the nature of work remains largely unsettled. Too many estimates of job losses serve as advertisements for AI services, often commissioned by AI companies themselves. Yet more grounded research increasingly points to the use of AI within the workplace and also to its surveillance capacities and harms. 16 These job changes are not preordained—workers are already pushing back against assumptions about how AI will be deployed and making AI use a core part of contract negotiations. 17

In order to work well, AI (and especially large language models) requires the labor of many workers and a vast infrastructure of data centers. Part of the illusion of AI is that it hides the people. Yet people are required to hand-create content, such as responses to chatbot prompts, and to label content. This includes the work of indicating whether a prompt response is satisfying or not to a human reader, whether a cat (or more often violence, especially sexual violence) is visible in an image, and so on. To be clear, workers in these jobs often labor under extremely exploitative conditions.18

Notably, however, workers and the problems of labor standards are not co-located with these data centers. AI systems require city-sized data centers for their creation and use, with high-speed internet infrastructure (Sen. Stevens’ “series of tubes”) between data centers and system users entering prompts. Within these data centers, the heart of the operation is state-of-the-art GPUs. These specialized chips allow for fast matrix operations, which are used to train neural networks efficiently. So many specialized chips are required that Nvidia Corporation (a chip manufacturer) is now a trillion dollar company. 19

While a substantial number of data-center jobs do not accrue to local communities, environmental impacts do. Data centers training and responding to queries for AI models use remarkable amounts of electricity, with projections that usage could spike to increase U.S. energy usage by between 5 percent and 20 percent by 2030. 20 Electricity bills are already rising in response.21 And concerns about the environmental health impacts of these AI factories are also increasing. 22

Water usage also is a problem, both for training and handling incoming queries from services such as ChatGPT, especially in local communities where water resources may already be tight.23 Yet companies have attempted to block these local communities from even knowing how much water they’re taking from the local water table. 24 In short, policymakers increasingly recognize that AI requires not just abstract thought but also a great deal of energy, water, and other critical resources. 25

Conclusion

We are starkly aware of a confidence asymmetry in AI policy—the gap between the assured claims from creators of AI and similarly automated systems and the uncertainty of state, local, and federal policymakers. This discrepancy is hindering effective and decisive policymaking.

In this paper, we offer a series of heuristics, not as a replacement for technical expertise, but to remind policymakers that AI systems are understandable within the context of specific policy choices. We urge policymakers to move with confidence by recognizing that questions about AI fall within existing policy domains, from industrial competitiveness and labor rights to nondiscrimination and consumer protection.

About the authors

Sorelle Friedler is the Shibulal Family Professor of Computer Science at Haverford College and a nonresident senior fellow at the Brookings Institution. She served as the assistant director for data and democracy in the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy under the Biden-Harris administration. Her research focuses on the fairness and interpretability of machine learning algorithms, with applications from criminal justice to materials discovery. Friedler is a co-founder of the ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency. She holds a Ph.D. in computer science from the University of Maryland, College Park, and a B.A. from Swarthmore College.

Marc Aidinoff is currently a postdoctoral researcher at the Institute for Advanced Study, a research associate at the Cornell Digital Due Process Clinic, and an incoming assistant professor of the history of technology at Harvard University. Aidinoff recently served as chief of staff in the Biden-Harris White House Office of Science and Technology Policy, where he helped lead a team of policymakers on key initiatives. Aidinoff holds a Ph.D. from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and B.A. from Harvard College.

Did you find this content informative and engaging?

Get updates and stay in tune with U.S. economic inequality and growth!

End Notes

1. Evan Dashevsky, “A Remembrance and Defense of Ted Stevens’ ‘Series of Tubes,’” PC Magazine, June 5, 2014, available at https://www.pcmag.com/news/a-remembrance-and-defense-of-ted-stevens-series-of-tubes

2. Nicole Starosielsko, The Undersea Network (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015), available at https://www.dukeupress.edu/the-undersea-network

3. Ellen P. Goodman, “Regulatory Analogies, LLMs, and Generative AI,” Critcal AI 2(1)(2024), available at https://read.dukeupress.edu/critical-ai/article-abstract/doi/10.1215/2834703X-11205238/390855/Regulatory-Analogies-LLMs-and-Generative-AI?redirectedFrom=fulltext; Marc Aidinoff and David I. Kaiser, “We’ve Been Here Before: Historical Precedents for Managing Artificial Intelligence.” In Kathleen Hall Jamieson, William Kearney, and Anne-Marie Mazza, eds., Realizing the Promise and Minimizing the Perils of AI for Science and the Scientific Community (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2024).

4. Sally Wyatt, “Metaphors in critical Internet and digital media studies,” New Media & Society 23(2) (2021): 406–416, available at https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1461444820929324; Kristen Jakobsen Osenga, “The Internet is Not a Super Highway: Using Metaphors to Communicate Information and Communications Policy,” Journal of Information Policy 3 (2013): 30–54, available at https://scholarship.richmond.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=&httpsredir=1&article=1047&context=law-faculty-publications.

5. Stephen Cave, “The Problem wth Intellifence: its Value-Laden History and the Future of AI,” AIES ’20: Proceedings of the AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society (2020): 29-35, available at https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3375627.3375813.

6. Virginia Eubanks, Automating inequality: How high-tech tools profile, police, and punish the poor (New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press, 2017); Sherry Turkle,“Who Do We Become When We Talk to Machines?” (Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2024), available at https://doi.org/10.21428/e4baedd9.caa10d84.

7. Andrew D. Selbst and others, “Fairness and Abstrction in Sociotechnical Systems,” FAT* ’19: Proceedings of the Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (2019): 59–68, available at https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3287560.3287598.

8. Shannon Vallor, The AI Mirror: How to Reclaim Our Humanity in an Age of Machine Thinking (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2024), available at https://global.oup.com/academic/product/the-ai-mirror-9780197759066?cc=us&lang=en&.

9. Emmanuel Martinez and Laren Kirchner, “The Secret Bias Hidden in Mortgage-Approval Algorithms,” The Markup, August 25, 2021, available at https://themarkup.org/denied/2021/08/25/the-secret-bias-hidden-in-mortgage-approval-algorithms.

10. Jeffrey Dastin, “Insight – Amazon scraps secret AI recruiting tool that showed bias against women,” Reuters, October 10, 2018, available at https://www.reuters.com/article/world/insight-amazon-scraps-secret-ai-recruiting-tool-that-showed-bias-against-women-idUSKCN1MK0AG/.

11. Ziad Obermeyer and others, “Dissecting racial bias in an algorithm used to manage the health of populations,” Science 366(6654)(2019): 447–453, available at https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.aax2342.

12. Lydia X.Z. Brown and others, “Ableism and Disability Discrimination in New Surveillance Technologies,” (Washington: The Center for Democracy and Technology, 2022), available at https://cdt.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/2022-05-23-CDT-Ableism-and-Disability-Discrimination-in-New-Surveillance-Technologies-report-final-redu.pdf; Tara García Mathewson, “AI Detection Tools Falsely Accuse International Students of Cheating,” The Markup, August 14, 2023, available at https://themarkup.org/machine-learning/2023/08/14/ai-detection-tools-falsely-accuse-international-students-of-cheating.

13. Cade Metz and others, “How Tech Giants Cut Corners to Harvest Data for A.I.,” The New York Times, updated April 8, 2024, available at https://www.nytimes.com/2024/04/06/technology/tech-giants-harvest-data-artificial-intelligence.html.

14. Will Knight, “Fast Forward,” Wired, February 22, 2024, available at https://link.wired.com/public/34436953.

15. David F. Noble, Forces of Production (New York, NY: Penguin Random House, 2013), available at https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/122338/forces-of-production-by-david-f-noble/; Stephen R. Barley, “Technology as an Occasion for Structuring: Evidence from Observations of CT Scanners and the Sociology of Radiology Departments,” Administrative Science Quarterly 31 (1) (1986): 78–108, available at https://ics.uci.edu/~corps/phaseii/Barley-CTScanners-ASQ.pdf.

16. Alexander Hertel-Fernandez, “Estimating the prevalence of automated management and surveillance technologies at work and their impact on workers’ well-being” (Washington, DC: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2024), available at https://equitablegrowth.org/research-paper/estimating-the-prevalence-of-automated-management-and-surveillance-technologies-at-work-and-their-impact-on-workers-well-being/.

17. Molly Kinder, “Hollywood writers went on strike to protect their livelihoods from generative AI. Their remarkable victory matters to all workers” (Washington: The Brookings Institution, 2024), available at https://www.brookings.edu/articles/hollywood-writers-went-on-strike-to-protect-their-livelihoods-from-generative-ai-their-remarkable-victory-matters-for-all-workers/.

18. Mary L. Gray and Siddharth Suri, Ghost work: How to stop Silicon Valley from building a new global underclass (New York, NY: Harper Business, 2019).

19. Derek Saul, “Nvidia Tops $2 Trillion Market Value for First Time Ever,” Forbes, February 23, 2024, available at https://www.forbes.com/sites/dereksaul/2024/02/23/nvidia-tops-2-trillion-market-value-for-first-time-ever/.

20. David Gelles, “A.I.’s Insatiable Appetite for Energy,” The New York Times, July 11, 2024, available at https://www.nytimes.com/2024/07/11/climate/artificial-intelligence-energy-usage.html.

21. Evan Halper and Caroline O’Donovan, “As data centers for AI strain the power grid, bills rise for everyday consumers,” The Washington Post, updated November 1, 2024, available at https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2024/11/01/ai-data-centers-electricity-bills-google-amazon/.

22. Yeulin Han and others, “The Unpaid Toll: Quantifying the Health Impact of AI” (Riverside, CA: University of California, Riverside, 2024), available at https://arxiv.org/pdf/2412.06288.

23. Pranshu Verma and Shelly Tan, “A bottle of water per email: the hidden environmental costs of using AI chatbots,” The Washington Post, September 18, 2024, available at https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2024/09/18/energy-ai-use-electricity-water-data-centers/; Abu Baker Siddik and others, “The environmental footprint of data centers in the United States,” Environmental Research Letters 16 (6) (2021) available at https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/abfba1.

24. Andrew Selsky, “Oregon city drops fight to keep Google water use private,” Associated Press, December 15, 2022, available at https://apnews.com/article/technology-business-oregon-the-dalles-climate-and-environment-f63f313b0ebde0d60aeb3dd58f51991c.

25. The White House, “Statement by President Biden on the Executive Order on Advancing U.S. Leadership in Artificial intelligence Infrastructure,” January 14, 2025, available at https://bidenwhitehouse.archives.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2025/01/14/statement-by-president-biden-on-the-executive-order-on-advancing-u-s-leadership-in-artificial-intelligence-infrastructure/.