Aligning U.S. labor law with worker preferences for labor representation

This essay is part of Vision 2020: Evidence for a stronger economy, a compilation of 21 essays presenting innovative, evidence-based, and concrete ideas to shape the 2020 policy debate. The authors in the new book include preeminent economists, political scientists, and sociologists who use cutting-edge research methods to answer some of the thorniest economic questions facing policymakers today.

To read more about the Vision 2020 book and download the full collection of essays, click here.

Overview

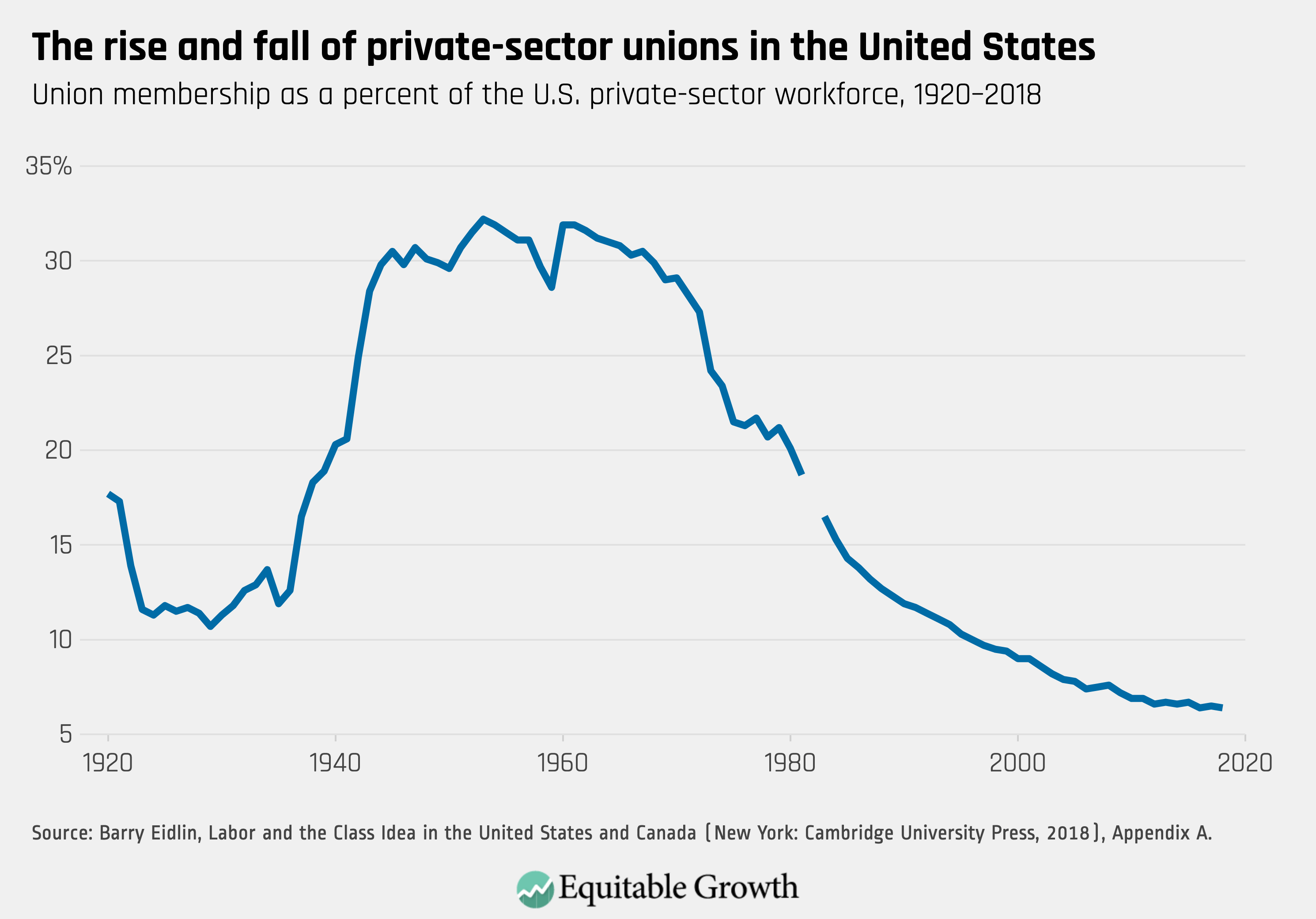

Just 6 percent of private-sector workers belong to a union in the United States, down from a peak of nearly a third in the early 1950s.1 Yet this steep decline in membership does not reflect a lack of worker demand for unions. If anything, workers’ interest in joining unions has increased over this period. In 2017, nearly half of all nonunion workers expressed interest in joining a union if one were available at their jobs.2 U.S. laws governing labor organizing and collective bargaining clearly do not reflect what most workers want.

Indeed, workers across the country are strongly supportive of some aspects of traditional unions, especially collective bargaining. They also value features of labor organizations that are either prohibited by existing federal and state labor laws or are not widely available, such as industry- or statewide collective bargaining and union-administered portable health and retirement benefits. These kinds of worker preferences for labor union representation have been suppressed in the United States for most of the 20th century up to today.

In this essay, I briefly examine the ossification of U.S. labor law over this time period, alongside the steady decline in union membership since the early 1960s. I then summarize new academic research that probes workers’ preferences for labor representation and organization that could inform reforms to federal labor law.3 I conclude by describing a range of possible federal legislation that could help bring labor law in line with the preferences espoused by majorities of U.S. workers—reforms that give workers greater access to representation and voice, broaden access to collective bargaining rights, build the provision of social benefits and training into unionization, and expand the scope of collective bargaining.

The ossification of U.S. labor law—and its heavy toll

Several trends are immediately apparent in the rise and fall of private-sector union membership in the U.S. labor force from 1920 to present day. First, membership remained relatively low until the mid-1930s. Amid the Great Depression, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed into law a sweeping bill intended to provide a comprehensive federal right for private-sector workers to organize unions and collectively bargain with their employers. Coupled with a later surge in wartime manufacturing, the National Labor Relations Act of 1935 boosted union membership to around a third of the private-sector workforce.

Yet, as important as the National Labor Relations Act was for the U.S. labor movement, the law still imposed substantial limits on union growth.4 It excluded large portions of workers from its reach, including the disproportionately nonwhite agricultural and domestic-workers labor force, as well as public-sector employees and any worker with supervisory or managerial duties, however limited. The law and subsequent amendments and court cases also sharply curbed union rights to picket, boycott, and strike against recalcitrant employers, thus weakening workers’ most important economic leverage. What’s more, penalties for employers who violated workers’ rights during union drives have remained low and poorly enforced, creating strong incentives for businesses to flout federal law.5

Most crucially, the law established a firm-based model of organizing and bargaining—as opposed to one where workers in an entire industry or region could bargain with broad swaths of employers. Firm-based bargaining may have worked well in an economy dominated by massive factories employing tens of thousands of workers. But today, when many employers contract or franchise out most of their workers, it makes unionization virtually impossible in many sectors.6 (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

These cracks in federal labor law—alongside the increasing brazenness of employers in opposing union drives—greatly contributed to the sharp decline in union membership since the 1960s and 1970s. Today, union membership in the private sector is now lower than it was before the passage of the National Labor Relations Act—and the fall in membership has exacted a significant toll on U.S. workers and the economy as a whole. Decades of research demonstrates that unions boost both unionized and nonunionized workers’ wages and benefits.7 Stronger unions also compress top-end pay, contributing to lower levels of income inequality.8 Aside from their effects on pay, unions give workers greater voice in the workplace, and this leads to safer and more equitable working conditions.9

Unions are important outside of the workplace, too. Stronger unions foster civic skills and political participation among workers and then channel that mobilization into representing the interests of low- and middle-income workers and their families.10 A number of studies indicate that economic policies are more aligned with the preferences of less-affluent citizens where union membership is higher.11

What workers want from labor representation

U.S. workers have not been clamoring for the demise of the labor movement. If anything, support for unions has actually increased over the past five decades. About a third of nonunion workers said that they would join a union if they could in 1977 and again in 1995, and this proportion grew to nearly half of all nonunion employees in a 2017 poll.12 Looking more broadly, more than 60 percent of workers in 2018 said that they approved of unions, compared to only 30 percent who disapproved.13

While these results indicate strong worker support for unions, they do not say much about the specific representation that workers would want from labor organizations. To answer that question, I have been working with Thomas Kochan and William Kimball at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Sloan School of Management to understand how workers think about workplace representation and the kinds of labor law reforms that would best match workers’ preferences. To that end, we have conducted large-scale, nationally representative surveys of workers, asking respondents to indicate how likely they would be to join and financially support various labor organizations. We varied how these organizations were structured, which permitted us to identify how much respondents valued individual characteristics of unions.

The characteristics we described in the survey included some common features of traditional U.S. unions, but also features of new organizations operating outside of conventional labor law (sometimes called “alt-labor” groups) and components of unions from other countries currently absent from the United States.

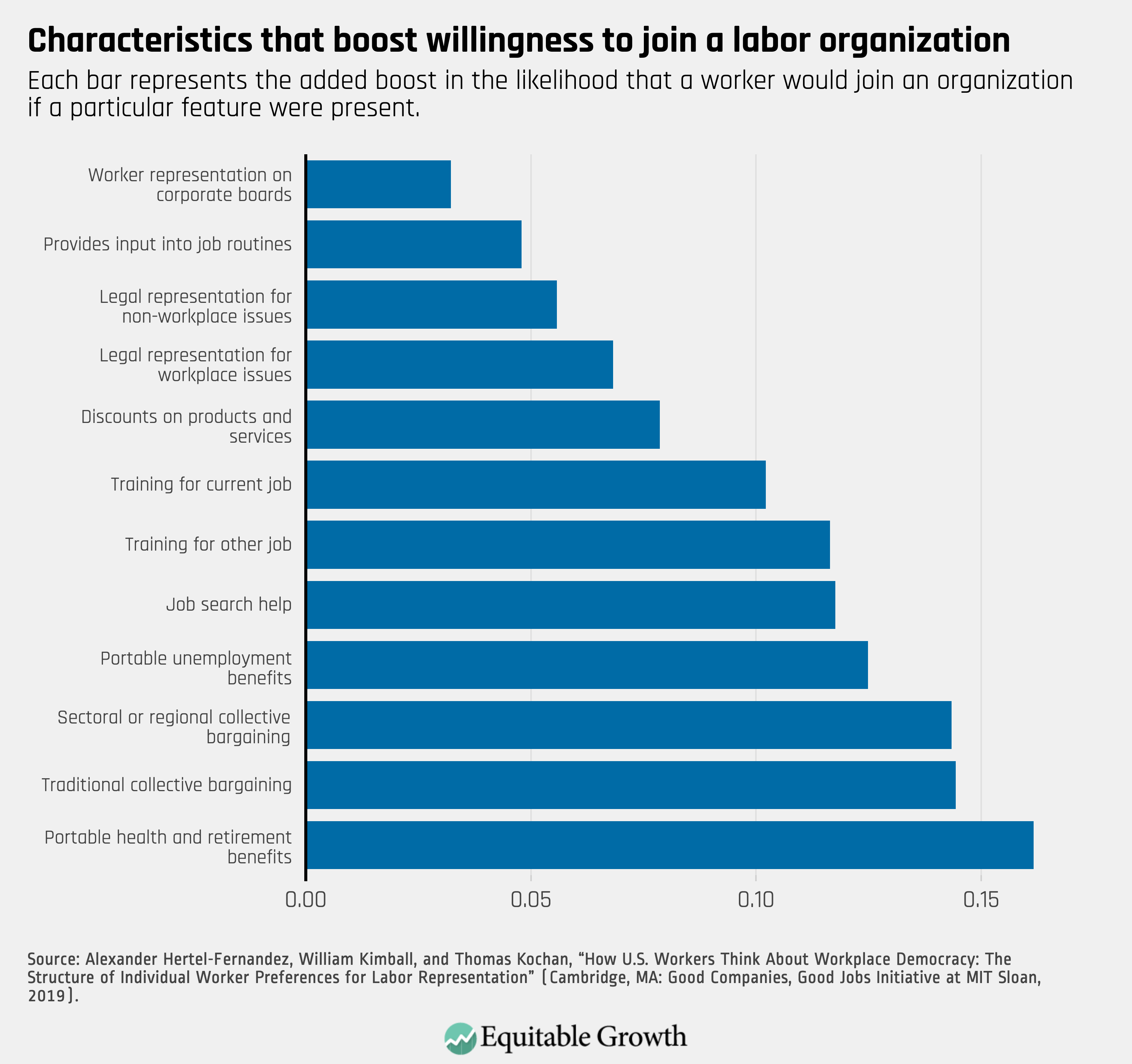

Which features of labor organizations were most—and least—important to workers? The most important features of hypothetical labor organizations to workers as they were considering whether they would join an organization include the following 12 characteristics in Figure 2. The presence of all of these features made workers more likely to say that they would join and support a labor organization. But some of these characteristics were clearly more popular than others. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

Several broad conclusions emerge from our findings. First, some features of traditional unions are still very popular with workers, especially collective bargaining at the firm or establishment level. But workers also voiced considerable enthusiasm for other potential features of labor organizations that are uncommon or even barred under current U.S. workplace law. Workers found the idea of sectoral or regional bargaining—much more common in Western Europe than in the United States—about as appealing as traditional collective bargaining. Expanding the scope of labor bargaining beyond the individual shop floor to whole industries or states would go far in rebuilding labor power in the United States, giving unions the opportunity to match the national scale of capital.

Another set of features that workers found very appealing involved portable social benefits administered through unions. Workers were substantially more likely to say they wanted to join unions that offered health insurance, retirement benefits, jobless benefits, and training and job search help that they could take with them from job to job. While some unions in the United States offer all those services, most do not. The provision of social benefits and training programs through unions could be an effective way for unions to attract new members, engage existing members more deeply, and raise revenue independent of member dues.

In fact, research indicates that the Nordic countries have managed to retain very high rates of union membership precisely because labor organizations in those countries are responsible for administering unemployment insurance and retraining programs.14 Similar findings from research I have conducted with public-sector unions in the United States also bolster this conclusion—providing highly valued benefits, such as training and professional development, to union members can foster increases in union interest and participation.15

The final bundle of attributes that attracted worker interest related to greater input in management decisions at the shop-floor level (determining how workers do their day-to-day jobs) and at the firmwide level (determining how businesses structure their operations). Unions in the United States have frequently shied away from these activities, even where they are legal.16 Our results buttress the idea that workers would be supportive of unions that did much more to gain voice on workplace issues, both small and large alike.

National reforms for building greater worker representation and voice

In all, our findings reveal a substantial gap between the labor organizations that workers say that they want and the representation they actually receive in the workplace. Not only do most workers who say they want traditional unions fail to receive any union representation at all, but current labor law also bars unions from offering many of the benefits and services that workers say they most value.

New federal legislation offers the most promise in overhauling labor law in the United States. There are several areas where policymakers ought to pursue change. Here are four proposals.

Giving workers greater access to representation and voice

At a basic level, Congress ought to make it easier for workers to form and join traditional unions. This means expediting union elections, giving union organizers greater rights to communicate with workers and share information about unions, and, above all, ensuring that employers have strong incentives not to violate existing worker protections. It also means strengthening workers’ rights to strike, boycott, and picket employers—without these tools, workers are outmatched against the economic and political strength of business.

More ambitiously, Congress might consider requiring regular union elections across all workplaces. Polling I have conducted indicates that only about 1 in 10 nonunion workers say they would know how to form a union at their job if they wanted to.17 Automatic, regularly scheduled union elections would thus go far in granting workers the functional right to form a union, regardless of whether there are union organizers at a worksite or if union leaders deem a workplace a strategic target.18 In a similar vein, Congress could mandate that all employers permit some minimal level of worker representation and voice—perhaps through joint management-worker committees—that could turn into, or complement, full-blown unions with collective bargaining rights if workers expressed sufficient interest.

Broadening access to collective bargaining rights

Given the importance of collective bargaining to U.S. workers, Congress ought to close the exclusions that exist in the National Labor Relations Act—specifically those that shut out many disproportionately minority workers from the benefits of such bargaining. All domestic workers and agricultural and public-sector employees should have the right to bargain with their employers, as should workers who are low-level or intermediate supervisors or managers.

Congress also should ensure that employers cannot simply turn workers into independent contractors to avoid unionization drives. Independent contractors and other self-employed individuals working for businesses that exercise substantial control over working conditions and pay should be permitted to organize and bargain with employers, just like conventional employees. Similarly, labor law should permit bargaining between workers and their immediate employers, as well as other businesses with substantial control over working conditions, as in franchise and contracting relationships. And Congress should ensure that employers bargain in good faith with newly recognized unions, rather than dragging out negotiations to end union drives.

Building the provision of social benefits and training into unions

Congress might create more opportunities for unions to provide the sort of social benefits and training opportunities that workers indicated they value very highly in my research. Unions are currently limited in their ability to offer health insurance and retirement plans as benefits in the organizing process, but they should be permitted to do so.

Congress also ought to free unions up to offer portable health and retirement plans to workers across entire industries. Union-administered plans could compete with employers and other private alternatives, raise nondues revenue for the union, and generate stronger incentives for workers to enroll as dues-paying members. Unions should have the legal right to manage these funds independently of employers—something they cannot do under current law.19

One especially promising approach to labor-administered social benefits is for Congress to permit states to run unemployment insurance benefits through unions, as is common in Northern European countries. Not only would union-run jobless funds give workers good reasons to join unions, but they could also be paired with high-quality training and job skills programs tailored to the needs of specific sectors and employers.

Expanding the scope of collective bargaining

On the most sweeping level, Congress could move the National Labor Relations Act beyond the traditional, firm-based model for organizing and bargaining by giving unions greater scope for representing workers across entire sectors or regions. While there are a number of different models that Congress might pursue, at a minimum lawmakers should set ground rules about how union and employer representatives would be defined and the rights and responsibilities of union, employer, and government representatives in bargaining and contract administration and enforcement.20

At the same time, moves toward broader levels of collective bargaining need to be accompanied by greater voice for workers at the shop-floor level. Accordingly, Congress might consider expanding the reach of unions to help address workers’ grievances in their day-to-day jobs. That could mean, for instance, combining sectoral or regional bargaining with mandatory worker committees as described above. Those committees could deal with shop-floor grievances and firm-specific contract negotiations, while sectoral or regional labor representatives negotiate broader wage and benefit standards.

Download FileAligning U.S. labor law with worker preferences for labor representation

Conclusion

As these reforms suggest, there is enormous scope for improving the representation and voice that workers possess on their jobs. Moving forward on these priorities will not only help better align labor law with worker preferences but also help to accomplish many of the other goals described in this set of policy essays. A reinvigorated U.S. labor movement holds the promise of directly boosting stagnant pay and benefits for workers, improving working conditions and safety, closing yawning gaps in compensation between business executives and the workers they employ, and curbing abuses of employer power in the U.S. labor market. More broadly, history suggests that policies aimed at broadly shared prosperity and growth are only possible when supported by vibrant unions.21 For all these reasons, an overhaul of U.S. labor law ought to be a top—and early priority—for the Congress and the president in 2021.

—Alexander Hertel-Fernandez is an assistant professor of international and public affairs at Columbia University.

End Notes

1. Barry Eidlin, Labor and the Class Idea in the United States and Canada (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2018), Appendix A.

2. Thomas A. Kochan and others, “Worker Voice in America: Is There a Gap Between What Workers Expect and What They Experience?” Industrial and Labor Relations Review 72 (1) (2019): 3–38.

3. This memo draws from Alexander Hertel-Fernandez, William Kimball, and Thomas Kochan, “How U.S. Workers Think About Workplace Democracy: The Structure of Individual Worker Preferences for Labor Representation” (Cambridge, MA: Good Companies, Good Jobs Initiative at MIT Sloan, 2019), available at https://gcgj.mit.edu/how-us-workers-think-about-workplace-democracy-structure-individual-worker-preferences-labor.

4. For general discussions, see Cynthia Estlund, “The Ossification of American Labor Law,” Columbia Law Review 102 (6) (2002); Kate Andrias, “The New Labor Law,” Yale Law Journal 126 (2) (2016).

5. Morris M. Kleiner and David Weil, “Evaluating the Effectiveness of National Labor Relations Act Remedies: Analysis and Comparison with Other Workplace Penalty Policies.” Working Paper No. 16626 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2010).

6. On changes in corporate structure, see David Weil, The Fissured Workplace (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2014).

7. See, canonically, Richard B. Freeman and James L. Medoff, What Do Unions Do? (New York: Basic Books, 1984); more recently, see Josh Bivens and others, “How today’s unions help working people” (Washington: Economic Policy Institute, 2017).

8. Henry S. Farber and others, “Unions and Inequality Over the Twentieth Century: New Evidence from Survey Data.” Working Paper No. 24587 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2018); Bruce Western and Jake Rosenfeld, “Unions, Norms, and the Rise in U.S. Wage Inequality,” American Sociological Review 76 (4) (2011): 513–37.

9. David Weil, “Are Mandated Health and Safety Committees Substitutes for or Supplements to Labor Unions?” Industrial and Labor Relations Review 52 (3) (1999): 339–60.

10. For a summary, see James Feigenbaum, Alexander Hertel-Fernandez, and Vanessa Williamson, “From the Bargaining Table to the Ballot Box: Political Effects of Right to Work Laws.” Working Paper No. 24259 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2019).

11. Presentation by Daniel Stegmueller, Michael Becher, and Konstantin Käppner, “Labor Unions and Unequal Representation,” Universite de Geneve, April 13-14, 2018, available at https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/b6cb/09ba8ea6eeea82da1ddc3ead47a819625c07.pdf.

12. Kochan and others, “Worker Voice in America,” p.20.

13. Lydia Saad, “Labor Union Approval Steady at 15-Year High,” Gallup News, August 30, 2018, available at https://news.gallup.com/poll/241679/labor-union-approval-steady-year-high.aspx.

14. Bruce Western, Between Class and Market: Postwar Unionization in the Capitalist Democracies (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1997).

15. Alexander Hertel-Fernandez and Ethan Porter, “Bread and Butter or Bread and Roses? Experimental Evidence on Why Public Sector Employees Support Unions.” Unpublished Working Paper (2019), available at https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/ahertel/files/alexethan_aug2018.pdf.

16. Thomas A. Kochan, Collective Bargaining and Industrial Relations: From Theory to Policy and Practice (Homewood, IL: R. D. Irwin, 1980).

17. Item reported in Hertel-Fernandez, Kimball, and Kochan, “How U.S. Workers Think About Workplace Democracy.”

18. For a fuller elaboration, see, for instance, Benjamin I. Sachs, “Enabling Employee Choice: A Structural Approach to the Rules of Union Organizing,” Harvard Law Review 123 (2010): 655–728.

19. Michael A. McCarthy, Dismantling Solidarity: Capitalist Politics and American Pensions Since the New Deal (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2017).

20. Kate Andrias and Brishen Rogers, “Rebuilding Worker Voice in Today’s Economy” (New York: The Roosevelt Institute, 2018).

21. Martin Gilens, Affluence and Influence: Economic Inequality and Political Power in America (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2012); Jacob S. Hacker and Paul Pierson, American Amnesia: How the War on Government Led Us to Forget What Made America Prosper (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2016).