Tariffs pose real risks to the U.S. labor market

Uncertainty around trade policy makes it difficult to discuss the current state of the U.S. labor market. Businesses, workers, and policymakers at all levels make decisions based on both what they know about economic conditions today and what they expect to happen in the future. But policy announcements have moved much faster than data collection over the past several weeks, leaving few ways to use the good information gathered over the first few months of 2025 to understand where the labor market might be headed.

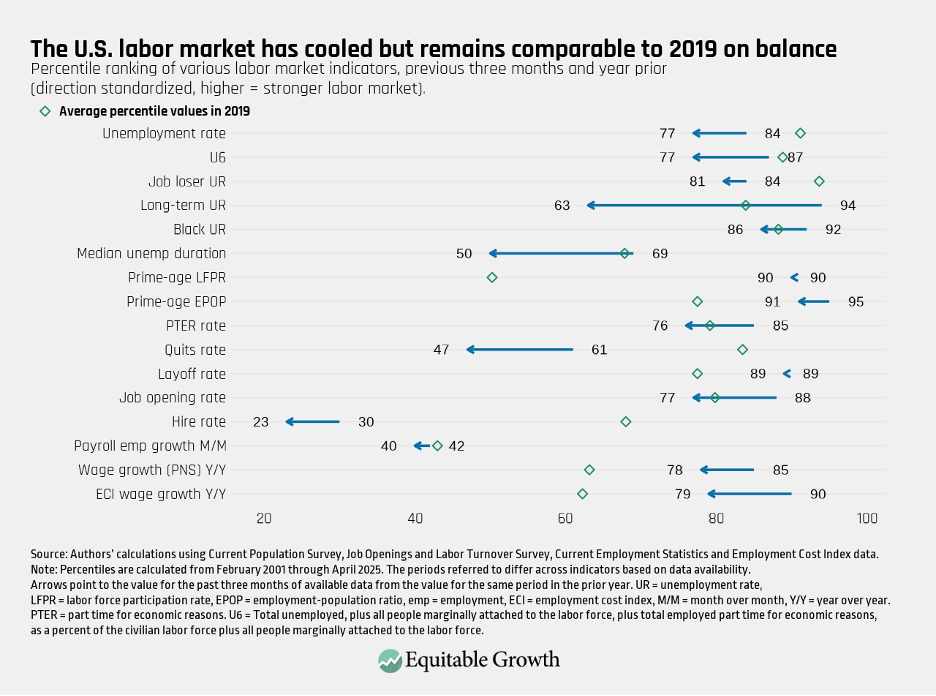

Fortunately, the available data suggest that the labor market remains solid, a sentiment echoed by Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell in his statement following last week’s Federal Open Market Committee meeting. Despite clear cooling over the past year, the early 2025 labor market still looks comparable to the 2019 labor market—when it was the strongest it had been since the late 1990s and early 2000s—across a range of indicators. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

Some measures, including the prime-age employment-to-population ratio and various measures of wage growth, remain consistently stronger in 2025 than they were in 2019. These measures are particularly important because they address directly how many people are working in a way that is not distorted by the aging of the U.S. population and what those workers who are working are taking home in wages—the most important things to know about how the labor market is functioning. Other indicators, such as the unemployment rate, hiring rate, and quits rate, are clearly weaker now than in 2019. Overall, though, a labor market with low unemployment by broader historical standards and growing real wages is a good one.

While the available data depict a labor market that was strong prior to the Trump administration’s April 2 tariff announcement, it is not clear whether that strength will endure in the face of the higher input costs, higher prices, and slower growth that the large tariffs would likely cause. Uncertainty about which tariffs will ultimately be levied is itself a headwind, as businesses that don’t know their future costs have a hard time making decisions about investment and hiring.

Although it is almost a fool’s errand to speculate about what exactly the tariff regime that emerges over the coming months will look like, it does seem extremely likely that it will have meaningful effects on U.S. labor market dynamics. Exploring how the unemployment rate could respond to various possible scenarios (without making any statement about the likelihood of any particular scenario) is therefore a useful exercise.

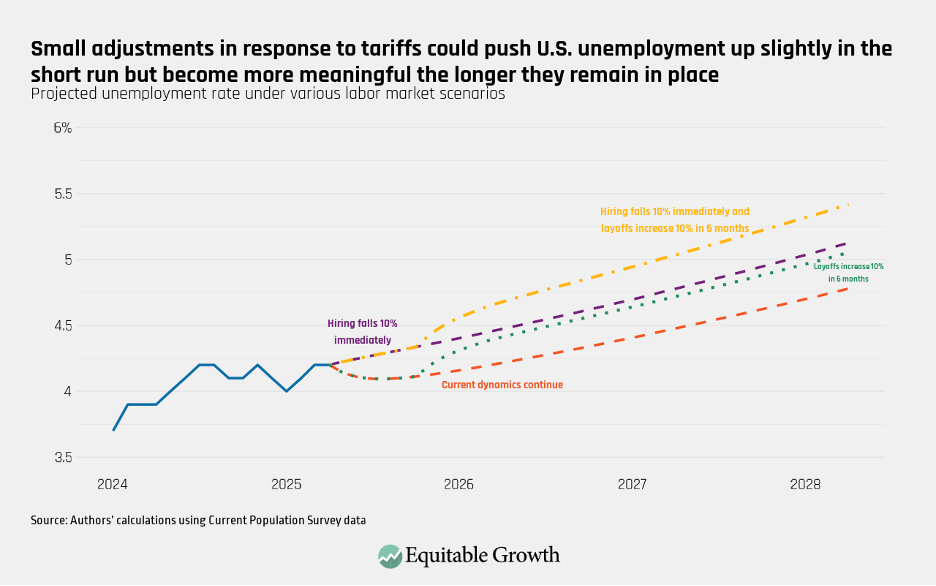

To set a baseline, applying a simple “bathtub model” of how workers are transitioning into and out of unemployment suggests that if current labor market dynamics were to continue, the unemployment rate would dip slightly over the next few months before returning to its current level of 4.2 percent in April 2026 and then rising modestly in each of the following 2 years, to 4.5 percent in April 2027 and 4.8 percent in April 2028. For comparison, these levels are within the range of values reported in the Federal Reserve’s final pre-tariff-announcement Summary of Economic Projections for 2026 and 2027.

Perhaps the most immediate labor market concern related to tariffs is that hiring could slow while uncertainty lingers about what the Trump administration’s trade policies will ultimately be. Unfavorable resolution of that uncertainty could also spark layoffs if tariffs reduce the viability of some businesses.

Figure 2 below presents simulations of the unemployment rate going forward if modest versions of these concerns play out individually, as well as if they both occur. Specifically, it shows what would happen if transitions from unemployment to employment (corresponding roughly to hiring) decline by 10 percent immediately; if transitions from employment to unemployment (corresponding roughly to layoffs) increase by 10 percent starting in 6 months; and if both of those things happen, as well as if current dynamics continue. Each scenario assumes other labor market dynamics (such as transitions between unemployment and being out of the labor force) continue to follow their recent trajectories. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

As Figure 2 shows, over the next year, each of these scenarios would increase unemployment slightly. If only hiring slows, then the unemployment rate would be 0.26 percentage points above baseline in April 2026. If only layoffs increase, then it would be 0.2 percentage points higher next April. If both happen, it would be 0.46 percentage points higher. The longer these adjustments remain in effect, the more substantial their impact. By April 2028, the unemployment rate would be 0.64 percentage points higher if hiring persistently falls by 10 percent immediately and layoffs persistently increase by 10 percent starting in 6 months.

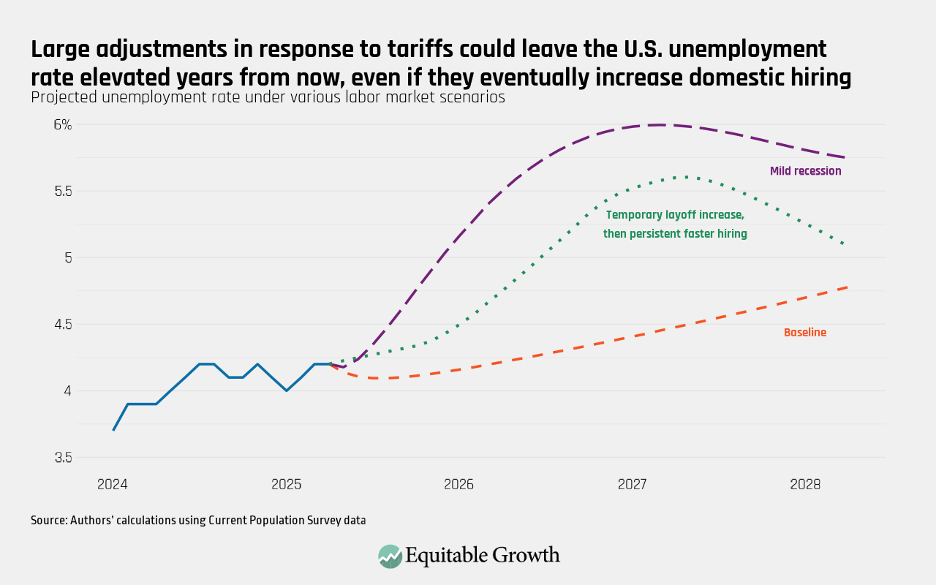

More substantial labor market adjustments, such as those shown below in Figure 3, are also well within the realm of possibility. Uncertainty-induced slowdowns in hiring could themselves lead to layoffs by reducing aggregate demand. Higher tariffs could lead more businesses to shut down. Disrupted relationships with overseas suppliers could take time to adjust to, slowing growth in the interim. Any or all of these dynamics could lead the economy to spiral into a recession. Even a fairly mild recession, with labor market dynamics analogous to the short recession in 2001, would drive the unemployment rate up to 6 percent by early 2027, more than 1.5 percentage points higher than the baseline scenario in which current labor market dynamics continue. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

Critically, there is no guarantee that a potential recession would merely be mild. The supply-side disruptions associated with substantial tariffs and the direct origins of a potential recession in discretionary and reversible policy choices would be without recent precedent, making it difficult to know how initial labor market responses might compound or be alleviated over time.

Some advocates for the aggressive use of tariffs argue that the short-term pain associated with adjusting to them will be outweighed by the longer-term gains associated with returning production of currently imported goods to the United States. The green line in Figure 3 illustrates a simple version of what this might look like. Specifically, it shows how the U.S. unemployment rate would respond if:

- Hiring from unemployment drops by 10 percent immediately, remains at that level for two years, and then starts increasing toward levels in line with business cycle peaks, getting halfway there by the end of the third year

- Separations to unemployment continue their recent trend for the next six months, then gradually increase (from the current low rate) to the long-run, pre-pandemic average rate over the following year, then decline back toward the current (low) rate, making it halfway back over the subsequent 18 months

- Other labor market dynamics continue to follow their recent trajectories

In a sense, this scenario is optimistic—arguably overly so—because transitions from employment to unemployment would remain below the long-run average rate (calculated across all points in the business cycle) while hiring from unemployment falls only modestly before approaching rates seen in the strongest U.S. labor markets. But despite this fairly favorable formulation, the unemployment rate would remain 0.3 percentage points above baseline in April 2028, and the trajectory between now and then is not that different from the trajectory associated with a mild recession (seen in purple in Figure 3).

This is an important point. The short-term pain that tariff advocates want to look past could very well be a mild (or not so mild) recession with the attendant long-term consequences for the millions of U.S. workers who could lose their jobs.

These specific scenarios might or might not come to pass, and it is impossible to say how likely they are. More or less extreme adjustments could also occur, depending on the ultimate path of U.S. trade policies and other developments in the U.S. and global economy.

These scenarios do, however, serve to ground thinking about the possible consequences of tariffs in concrete magnitudes associated with specific changes in the U.S. labor market. In so doing, they make one important point clear: While the U.S. labor market is still on solid ground, there is a very real risk of reversion to the kind of labor market conditions that leave people who want to work on the sidelines and allow real wages to stagnate.