Weekend reading: Public investments in care infrastructure edition

This is a post we publish each Friday with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth published this week and the second is relevant and interesting articles we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

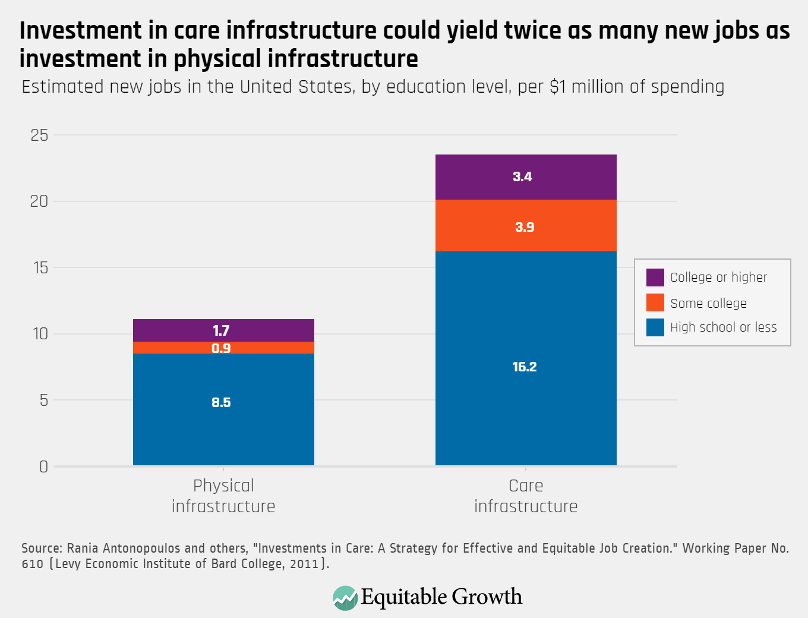

Many Americans do not have the caregiving support they need in order to physically return to an office or workplace once the coronavirus pandemic wanes. This was an issue long before the onset of the pandemic and subsequent recession, but the past year only deepened the existing cracks in our nation’s care infrastructure. As policymakers consider President Joe Biden’s American Jobs Plan and forthcoming American Families Plan—his multipart investment proposal for boosting infrastructure and creating good jobs—Equitable Growth released a factsheet on U.S. care infrastructure and what the research says about its impact on the U.S. economy. It highlights recent studies on the state of the care economy, how undervalued caregiving is in the United States, and the impact that public investment in care infrastructure can have on economic growth, labor force participation (particularly among women and workers of color), and worker well-being. This research shows that policymakers must consider investments in both care and physical infrastructure in order to jumpstart the economic recovery from the coronavirus recession and support workers who are currently being forced to choose between receiving a paycheck and caring for loved ones or themselves.

There was a time in recent U.S. history in which care was part of infrastructure: the World War II era. Sam Abbott details the Lanham Act, which was passed in response to women’s increased labor force participation amid the war effort of the early to mid-1940s. This law was not, by definition, a child care bill, but nonetheless created government-funded child care centers in more than 650 communities with defense industries across the United States in order to support mothers on the factory lines and fathers on the front lines of battle. Regardless of income, families could send their children to Lanham Act centers for $11 per day (adjusting for inflation). These centers closed down in 1946, but research on the few years they were open reveals both short- and long-term benefits for women’s attachment to the labor force and for their children’s education and employment outcomes years later. This has important implications now, Abbott explains, as policymakers consider investments in both physical and care infrastructure to ensure an equitable post-pandemic economy.

Recently, Equitable Growth relaunched our Research on Tap series, with a virtual event focused on investing in an equitable future co-hosted by the Groundwork Collaborative. The event kicked off with a conversation between Cecilia Rouse, the chair of the White House Council of Economic Advisers, and reporter Tracy Jan from The Washington Post, followed by a discussion on the need for structural changes among a panel of economic and social policy experts. The panel included Jhumpa Bhattacharya, vice president of programs and strategy at the Insight Center for Community Economic Development; Joelle Gamble, a special assistant to the president for economic policy on the White House National Economic Council; and Saule Omarova, a Cornell University law professor; and was moderated by Equitable Growth’s Policy Director Amanda Fischer. The event centered on the idea that markets alone cannot address the large structural challenges facing the country, including climate change, systemic racism and discrimination, and the lack of a 21st century care infrastructure. Instead, government must work together with the private sector to find solutions to these complex issues. Read our recap of the event to find out more about the policy ideas and reforms discussed that would ensure a stronger, more equitable future economy than the one with which the United States entered the pandemic.

In the latest installment of Equitable Growth in Conversation, Alix Gould-Werth speaks with Mark Rank, the Herbert S. Hadley professor of social welfare at Washington University in St. Louis, where he studies issues of poverty, inequality, and social justice in the United States. Their conversation touches upon different aspects of poverty in the United States, from how to usefully measure it and the actual causes of it, to poverty myths and their consequences. One important finding of Rank’s research that comes up is that the nearly 60 percent of Americans between the ages of 20 and 75 will experience at least 1 year in poverty, and three-quarters of Americans will experience either poverty or near-poverty in their lifetimes. Rank and Gould-Werth also discuss the intersections of poverty with race, inequality, the macroeconomy, and policymaking in the United States. Their conversation is a fascinating preview of next week’s Equitable Growth virtual event featuring Rank, Equitable Growth Presents: Dispelling Poverty Myths and Expanding Income Support.

Climate change is an incredibly complex policy issue, one that does not have a simple solution. But a policy workshop last year looked at the promises and challenges of carbon pricing as a path forward for reducing carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gas pollution in the United States. Gernot Wagner details the discussions at the conference, including how to price carbon, how to spend the revenues that may accrue from this policy, ways to foster innovation in this sector, and aligning carbon pricing policies with other measures that regulate emissions and fuel use. He also explains the political hurdles that could stand in the way of carbon pricing regulations, reviews the states and regions that have already been successful in implementing carbon pricing policies, and summarizes key recommendations that came out of the policy workshop for the Biden administration.

Links from around the web

There is a mountain of evidence that early childhood education and child care programs are beneficial not only for working parents and their children but also for the broader economy. So why is this industry so convoluted, unaffordable, and inaccessible to so many families? Vox’s Anne Helen Petersen proposes a straightforward solution: Make caring for children a good job with a livable wage, and make child care free and accessible for families. In 2019, the average early childhood worker was paid $11.65 per hour, or $24,230 per year—hardly enough to pay the bills, let alone save up or afford an emergency expense—yet the cost of sending a child to day care is increasingly out of reach for low- and middle-income families. This, Petersen writes, is the hallmark of a broken system. The first step toward fixing it involves changing the broader public’s thinking around caregiving work to that of a public good, much like we think of sanitation or libraries: essential to a functioning society, with no limits—financial, educational, geographic, or otherwise—on who can access it. Petersen explains how policymakers can go about this, and also looks at why it hasn’t been done thus far.

The American Rescue Plan’s extension and expansion of the child allowance is expected to cut child poverty in half—a significant achievement, considering that poverty leads to worse educational, health, and employment outcomes for children later in life. New research also looks at how poverty affects brain development among babies and young children, finding that those raised in poverty have subtle brain differences than their better-off peers, writes Alla Katsnelson in The New York Times’ The Upshot. The study examines whether reducing poverty itself can promote healthy brain development, studying the impact of providing families with cash payments that are comparable in size to those in the American Rescue Plan on future outcomes for children. Though it’s unclear what the policy implications will be, if any can be discerned at all, it could be an important insight into the role poverty plays in both individual lives and in future economic circumstances.

Though unionization efforts at an Amazon.com Inc. warehouse failed last week, the experience was illuminating, writes The New York Times’ Paul Krugman, highlighting the “continuing effectiveness of the tactics employers have repeatedly used to defeat organizing efforts.” But workers and labor advocates should not give up, Krugman continues. The United States needs unions in order to counteract expanding economic inequality and wage stagnation in this country—history itself shows the role unions play in ensuring an equitable economy for U.S. workers. Policy decisions in the 1980s reduced the size and scope of union membership, to disastrous effect for workers and their families, with more severe impacts than globalization and automation in lowering wages in the United States. Krugman explains how restoring the power and strength of unions would go a long way to boosting wages and reducing wage disparities among the U.S. workforce—and would work to level the political playing field as well.

The field of economics has a diversity problem—this is an undeniable fact. Indeed, this week, top policymakers at the Federal Reserve acknowledged and lamented that Black and Hispanic people are severely underrepresented among economists, reducing the effectiveness of policy decisions by limiting the perspectives that contribute. AP’s Christopher Rugaber covers the webinar, sponsored by the 12 regional Fed banks, in which top officials and experts, alongside leading economists and press, addressed the issue of diversity in economics. The Fed itself has an issue with diversity, with most leading policymakers being White males with a business background—an issue that was highlighted by a recent Brookings Institution report.

Friday figure

Figure is from Equitable Growth’s “Factsheet: What does the research say about care infrastructure?”