Weekend reading: Racial and gender inequalities in the coronavirus recession edition

This is a post we publish each Friday with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth published this week and the second is relevant and interesting articles we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

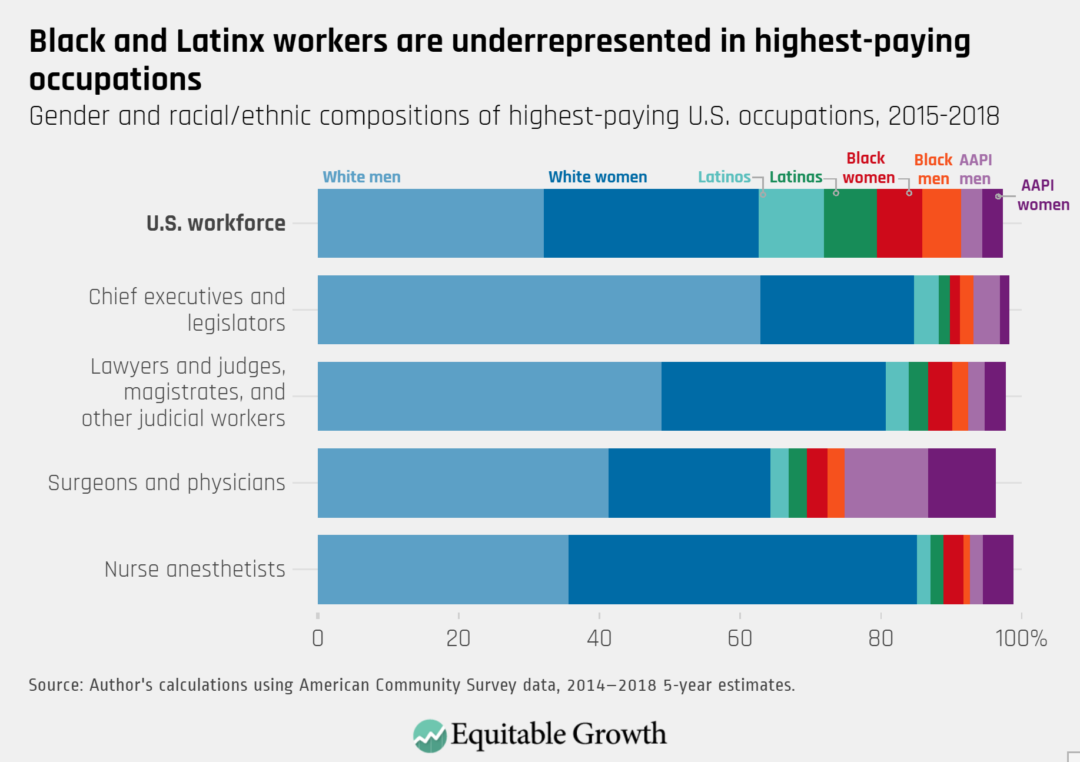

Occupational segregation—the overrepresentation or underrepresentation of demographic groups in certain industries and jobs—hurts the entire U.S. economy by entrenching racial and gender wage gaps, lowering earnings for all workers, and preventing workers from entering their preferred professions. This trend is rampant in the U.S. labor force, write Kate Bahn and Carmen Sanchez Cumming, crowding certain groups of workers into some jobs and limiting their access to other, better, or higher-paying positions. For instance, White men still make up the majority of those in top-paying jobs, such as CEOs, while women, and women of color in particular, tend to make up a higher proportion of workers in lower-wage, more insecure jobs and jobs in the service sector. This job stratification along the lines of race, ethnicity, and gender tend to lead to devaluation of certain types of jobs and industries, which exacerbates wealth and income divides and puts women and workers of color at higher risk of hardship during recessions. Bahn and Sanchez Cumming put together four graphics to showcase occupational segregation in the workforce by race and gender, as well as a factsheet with more information on this trend and its impact on recessions and other troubling trends such as income and wealth inequality.

Bahn and Sanchez Cumming also relate occupational segregation to the most recent Jobs Report, using unemployment data released yesterday to show how these pre-existing inequalities are getting worse during the coronavirus recession. The data, released by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, indicate that Black and Latinx workers continue to be worse-off in terms of job losses during the economic downturn caused by the pandemic. Despite overall unemployment falling between May 2020 and June 2020, a higher percentage of women, Black, Latinx, and low-wage workers are unemployed, compared to their White, male, and better-off counterparts. As Bahn and Sanchez Cumming show, occupational segregation plays an outsize role in funneling these more vulnerable workers into the jobs and sectors that have been hardest hit in the recession, such as service, retail, and care positions.

Likewise, as women tend to do more of the unpaid care work in households, the health crisis caused by the coronavirus pandemic is falling more heavily on women’s shoulders. Kate Bahn, Jennifer Cohen, and Yana van der Meulen Rodgers expand on this insight in their column on feminist economics, the pandemic, and the fight for racial justice. The co-authors explain how the coronavirus crisis has highlighted the foundational role of care in U.S. society, both within families and households, as well as across communities, while also showcasing how undervalued this work has been and how it has become gendered and racialized. They then describe why any future comprehensive response to the pandemic must recognize how integral care work is to a society and economy that prioritizes human well-being.

Also essential to any future coronavirus recession-related legislation are automatic stabilizers, or programs that wind up and ramp down automatically depending on certain economic indicators, such as the unemployment rate. Greg Leiserson examines the critical role these policies—proposed in Equitable Growth and The Hamilton Project’s 2019 publication Recession Ready—can play to speed up the recovery now and aid in future recessions. Leiserson first defines how economists measure recessions and mark the onset of downturns, how public policy plays a role during recessions, and why the coronavirus recession is different from past recessions and thus deserves a different approach. He then runs through what policymakers have already done to address the coronavirus crises on both public health and economic fronts, and why the uncertainties surrounding this recession, its length, and its impact make automatic stabilizers a particularly smart policy for lawmakers to enact.

Last week, Equitable Growth held a webinar on structural change and economic recovery as part of our Vision 2020 initiative to discuss transformative ideas for 2020 U.S. economic policy debate. Panelists discussed ideas from canceling all federal student loan debt to eliminating banks as the “middleman” for anti-recession federal aid. Read about more of the proposals and watch recordings of the two panels here.

Links from around the web

Despite the monthly joblessness rate declines in May and June, unemployment in the United States still stands above the previous peak of 10 percent, during the Great Recession of 2007–2009. The jobs crisis is far from over, writes Anneken Tappe for CNN Business. Millions of jobs have been shed from the economy in a mere 4 months and even after 2 months of solid growth, the unemployment rate is still shockingly high, especially considering that it was near a 50-year high of 3.5 percent in February. The pain from this recession has not been spread evenly throughout the economy, and even as the aggregate numbers appear to be improving, Tappe continues, the U.S. labor market is still facing tough times ahead.

The student loan crisis is perpetuating inequality in Black and Latinx communities that exacerbates the racial wealth divide and holds back Americans of color in the middle of the pandemic and economic crisis, writes Erik Ortiz for NBC News. Looking at a new report released by the Student Borrower Protection Center, which studied borrower data from regional Federal Reserve banks and city governments in New York City, Washington, D.C., Philadelphia, and San Francisco, Ortiz explains the results showing those in majority Black and Latinx neighborhoods are more reliant on loans and take on more debt. These communities are more likely to take out loans because they don’t have the same levels of intergenerational wealth as their White peers do, and they disproportionately struggle to pay back their loans because they tend to be pushed into lower-paying jobs, thanks in part to occupational segregation. These lower-paying jobs make it harder for workers of color to build wealth, and thus the cycle continues.

Long-term trends in the U.S. economy that favor profits over people and drive the decline in union membership and power have caused a level of inequality and disparity between those at the top of the wealth and income ladders and the rest of us that is on full display in the coronavirus recession. “COVID-19 has brought into sharp relief the contrast between the experiences of the higher-income Americans who receive deliveries and the lower-income Americans who fulfill them, between those who can work safely from home and those who must expose themselves to risk, often with inadequate protection, between those who have the power to safeguard their health and their living standards and those who do not,” write Lawrence H. Summers and Anna Stansbury for The Washington Post. These trends have exacerbated the racial and gender income and wealth divides in our economy. Now, more than ever, workers need more power and higher wages. Summers and Stansbury briefly run through how we got to this point and then push for several approaches policymakers can take to increase worker power.

Amid the coronavirus recession, working parents are like candles being burned from both ends. Those lucky to still have jobs and be able to work from home are also having simultaneously to care for their children, run an impromptu homeschool, and/or babysit. As if this wasn’t tough enough, as the U.S. economy reopens and workers are expected back in the office, many public schools are facing new restrictions for health reasons that will leave children at home rather than at school for much of the time. Where does this leave working parents? It seems, writes Deb Perelman in The New York Times, as though you’re “allowed” either a kid or a job, not both. Perelman runs through various arguments (very valid, in some cases) against fully reopening schools and then explains why all the proposed solutions are untenable for most working parents using her family’s experience over the past four months as an example.

Friday figure

Figure is from Equitable Growth’s “Four graphs on U.S. occupational segregation by race, ethnicity, and gender” by Kate Bahn and Carmen Sanchez Cumming.