Weekend reading: The structural changes needed to fight the coronavirus recession edition

This is a post we publish each Friday with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth published this week and the second is relevant and interesting articles we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

Rising economic inequality left the U.S. economy and society particularly vulnerable in the face of the public health and economic crises caused by the coronavirus pandemic and ensuing recession, write Heather Boushey and Somin Park. After reviewing vulnerabilities that reinforce and deepen inequality in the United States, Boushey and Park suggest several broad policy ideas that lawmakers can consider now to better prepare to combat the sudden recession and the economic recovery, from addressing fragilities in our markets and leaving behind the idea that markets can do the work of government, to keeping income flowing to people and businesses and ensuring workers who are still employed can stay employed. And, while data collection may seem like a distant concern in times like these, Boushey and Park explain why getting accurate statistics that show how everyone across the U.S. economy is faring is a vital step in identifying entrenched structural weaknesses and enacting policies to repair and reverse them. Unless these vulnerabilities are addressed, the United States will emerge from yet another recession with unsustainable inequalities in income and wealth that further inhibit our ability to recover from crises.

One way to try to mitigate the effects of the coronavirus recession is to bolster small businesses in the United States, writes Amanda Fischer, a step that will have the added benefit of reducing economic inequality down the road. While the recently enacted Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security, or CARES, Act did provide for hundreds of billions of dollars for struggling small businesses, reports from the White House this past week indicate that this funding has already dried up. More must be done to support small businesses, and it must be easier for them to gain access to this support, Fischer argues, looking at lessons learned from the implementation of the CARES Act, as well as the big business supports within the bill, to develop a set of proposals for how policymakers can move forward.

Policymakers can also use fiscal policy to fight both the public health threat caused by COVID-19, the disease the new coronavirus spreads, and the economic downturn. Guest columnist Olivier Blanchard presented three fiscal policy ideas in a recent online conference for more than 100 economists organized by Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman of the University of California, Berkeley to discuss the coronavirus pandemic and recession. Blanchard summarizes his three recommended tasks ahead for fiscal policymakers, and shows why potentially incurring more debt should not be more of a concern for developed economies than doing whatever it takes to get the disease under control.

The coronavirus recession is exposing just how badly gig economy workers and independent contractors are treated under U.S. labor law, write Corey Husak and Carmen Sanchez Cumming. These workers make up 7 percent of the U.S. workforce, yet they do not receive most, if not all, of the basic benefits that make up the labor safety net, from employer-provided healthcare to the ability to join a union. They also tend to be on the front lines of the current crisis, as home care aides or delivery workers, or facing high levels of unemployment, as ride-hailing drivers, artists, or salon employees. While the CARES Act took the unprecedented step to include these workers temporarily in the eligibility pool for Unemployment Insurance, many states still are not accepting claims submitted by self-employed workers largely as a result of the overwhelming burden many unemployment offices are currently facing. Husak and Sanchez Cumming detail three policies lawmakers should consider to support these left-behind workers as they navigate the coronavirus recession and public health crisis.

The coronavirus pandemic highlights the enormous racial gaps in who is affected, from both a public health and an economic standpoint across the United States, writes Austin Clemens, as well as the necessity for disaggregating data by race and ethnicity. Marginalized populations are not only more exposed to the coronavirus because they are more likely to be working in “essential” industries that must remain open during the crisis, they also are more likely to have underlying health conditions such as asthma due to a long history of policy failures that disproportionately affect vulnerable communities. Adopting colorblind policies that fail to address the fact that certain people are more exposed to COVID-19, the disease spread by the coronavirus, will only reinforce the structural racism that made those people vulnerable to begin with. And while having disaggregated data will not alone tackle these issues, Clemens argues, gathering these data will help policymakers target their responses more appropriately.

Links from around the web

Headlines increasingly call out the racial disparities in who is getting infected by the new coronavirus and who is dying from COVID-19 in the United States, with political leaders increasingly lament these disparities. But will they actually do something about the structural and historical racism at the root of the issue? In an in-depth look in The New Yorker at the effect of the coronavirus on black communities, Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor reviews the history of U.S. policies that cause African Americans to have worse health outcomes, socioeconomic standing, employment options, and housing opportunities, as well as the Trump administration’s inadequate response to the coronavirus pandemic and how it has impacted marginalized populations more than their better-off peers. If policymakers truly want to address the disparities faced by black communities in the United States—with regard to coronavirus and COVID-19, as well as future public health crises that are bound to arise—then Taylor says that systemic and structural changes, not superficial fixes, are needed to level the playing field.

Hardly any grocery store workers—who are deemed emergency workers and are still going into work every day amid the coronavirus pandemic—have access to adequate paid sick leave if they contract COVID-19. According to a new study, only 55 percent of workers at large U.S. stores get paid sick time, and just 8 percent could take the recommended two weeks off to self-quarantine after exposure the new coronavirus, reports Emily Peck for the Huffington Post. This not only puts these workers and their families at risk, but also threatens public health. Despite Congress including paid sick leave provisions in the second coronavirus legislative package passed in March, loopholes and exclusions for large companies mean that just 25 percent of workers across the U.S. economy actually gained access to paid leave.

New research from Columbia University says the coronavirus public health and economic crises will cause a sharp increase in the U.S. poverty rate, which likely will exacerbate existing racial inequalities and will disproportionately affect children. Poverty levels could easily reach 15.4 percent, writes Jason DeParle for The New York Times’ The Upshot, even if the economy recovers immediately—which is highly unlikely. And while the model that the Columbia researchers crafted doesn’t fully take into account the potential antipoverty effects of measures within the CARES Act, its predictions suggest “a coming poverty epoch, rather than an episode.”

Millennials are facing their second “once in a lifetime” economic downturn at a crucial moment in many of their careers, and this all but guarantees that many will end up worse-off than their parents, writes Annie Lowrey for The Atlantic. Millennials entered the workforce during the Great Recession of 2007–2009 and, as such, are more vulnerable to economic hardships than their parents ever were. Previous generations were better prepared to weather recessions because of the financial cushions they had the opportunity to build. But millennials have smaller savings accounts, fewer investments, lower home-ownership rates, higher levels of student loan debt, and they earn less money. And while recessions are never good for any age group or type of worker, millennials are now entering the phases of their careers where they should be starting to earn their peak salaries—and are, for the second time, being battered by a severe economic downturn.

Friday figure

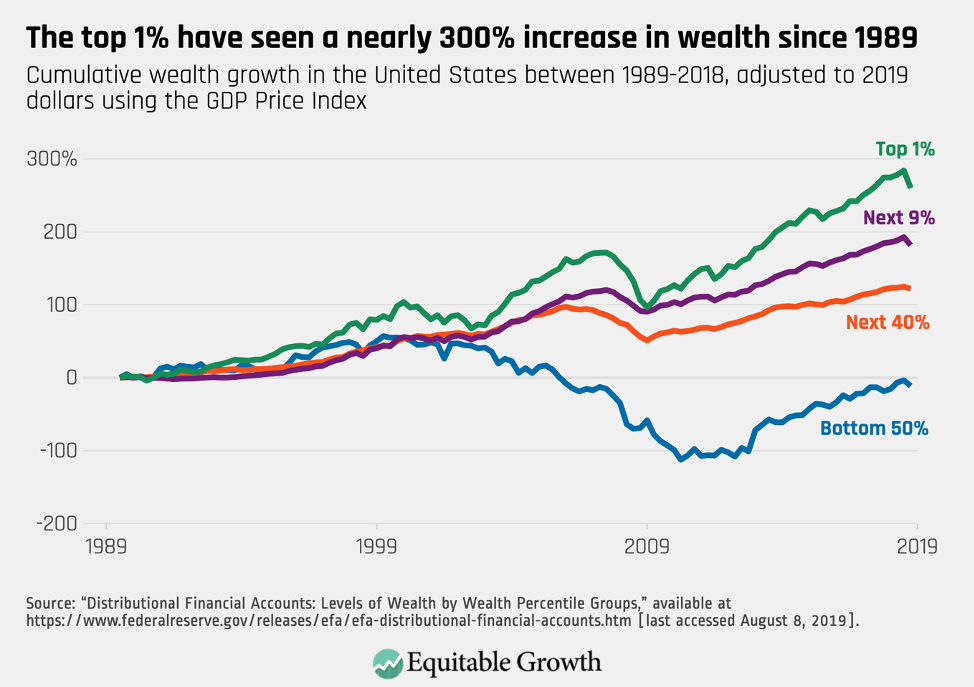

Figure is from Equitable Growth’s “Rescuing small businesses to fight the coronavirus recession and prevent further economic inequality in the United States” by Amanda Fischer.