Weekend reading: Helping the hardest-hit during the coronavirus outbreak edition

This is a post we publish each Friday with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth published this week and the second is relevant and interesting articles we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

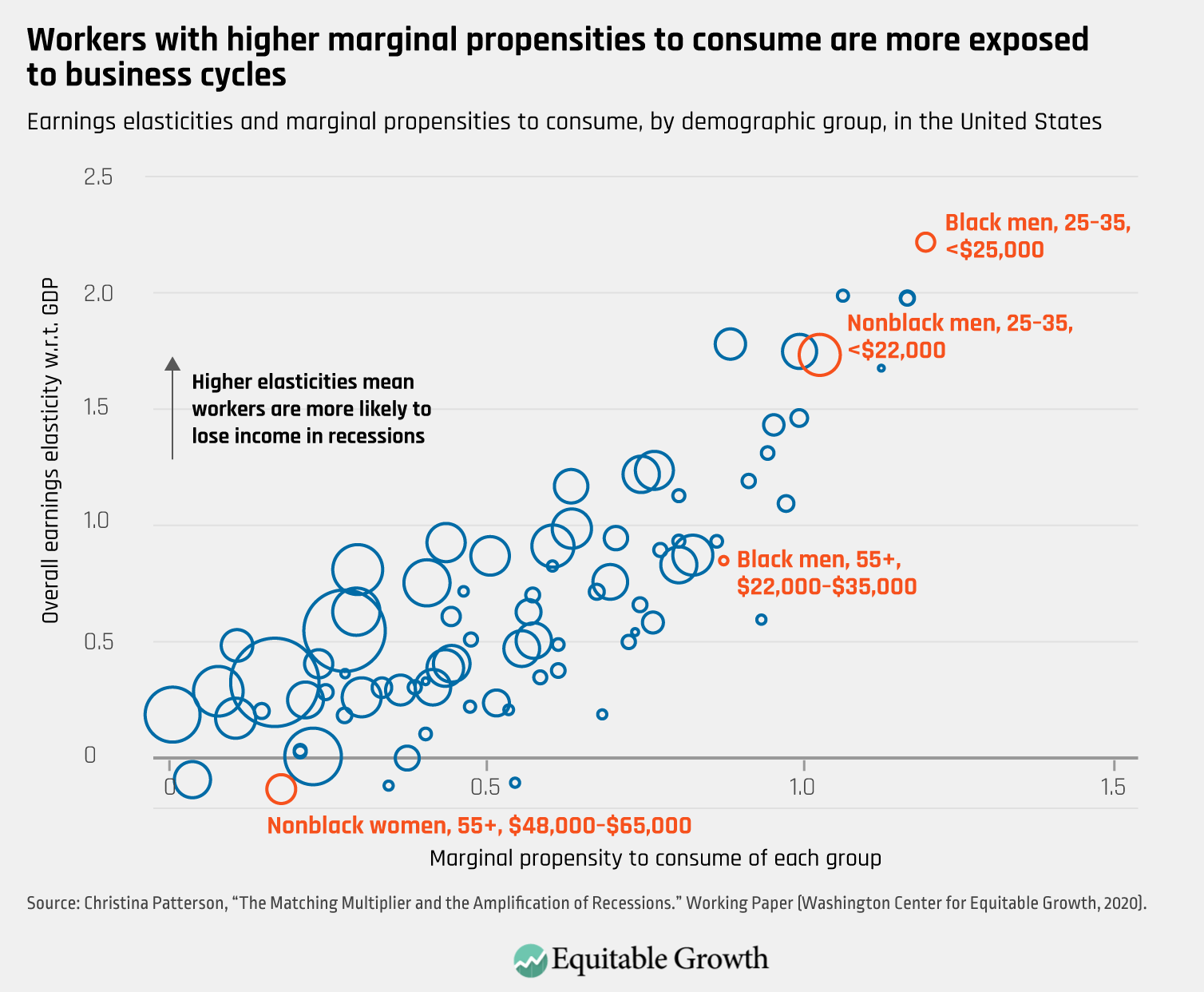

New research shows that those workers whose earnings are hit hardest during recessions are also those whose consumption is most sensitive to drops in income. When these mostly young and low-income workers are laid off, they drastically cut their consumption and spending, which makes economic recovery harder and slower to achieve. Christina Patterson explains her research about the effects of recessions on workers’ marginal propensities to consume, which looks at how much consumption falls for each unit of lost income. She also shows how certain industries and occupations tend to have higher proportions of workers with high MPCs—and these are exactly the ones that have already been impacted by the coronavirus recession. The struggles these sectors and their workers face can amplify recessions by decreasing overall demand and consumption across the economy. In light of this, Patterson argues that lawmakers should prioritize those workers with high MPCs when distributing stimulus money from the $2.2 trillion coronavirus relief package in the coming weeks and months.

As scientists around the world look for a cure for COVID-19, the disease caused by the new coronavirus, economists and social scientists are also studying the effects of the pandemic. Studies are looking into a range of subjects, from the public health ramifications of COVID-19, to the economic costs of the outbreak and social distancing, to whether quarantines and lockdowns are effective in preventing the spread of the disease. Equitable Growth highlights 10 new workings papers to give an overview of the diverse research being done on this pandemic and where we go from here.

Three important questions regarding U.S. financial stabilization policies must be answered in today’s financial and economic reality, writes J. Nellie Liang of The Brookings Institution, in a summary of her remarks in a video conference on the coronavirus recession organized by Equitable Growth Steering Committee member Emmanuel Saez and Equitable Growth grantee Gabriel Zucman at the University of California, Berkeley. Where do these policies fit into the overall set of policy responses? What has been done so far? And what still needs to be done? Liang answers each of these in turn, showing how financial stabilization policies work with public health responses and fiscal policy to address crises by reducing the cost of borrowing and ensuring the flow of credit to households and businesses. Liang argues that more needs to be done to help small and mid-size businesses stay afloat during the coronavirus recession, to address the consequences when people and businesses will defer their mortgage payments, and to ensure that banks can weather the recession and emerge from it quickly.

Every month, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics releases data on hiring, firing, and other labor market flows from the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey, better known as JOLTS. This week, the February 2020 data were released. This report doesn’t get as much attention as the monthly Employment Situation Report, but it contains useful information about the state of the U.S. labor market. Kate Bahn and Carmen Sanchez Cumming put together four graphs using data from the report, which show that prior to the unexpected economic crisis resulting from the coronavirus pandemic, low unemployment and a steady quit rate signaled a strong labor market.

Links from around the web

While many white-collar workers have made the move to telecommuting, many lower-income workers are still leaving the safety of their homes to take public transit, go to work, and provide needed services for the rest of us—and The New York Times has the smartphone data to prove it. Jennifer Valentino-DeVries, Denise Lu, and Gabriel J.X. Dance analyze that data and confirm that while people across income groups are moving around less than they did before, wealthier people are able to do so less often than their worse-off peers. Additionally, they write, “in nearly every state, they began doing so days before the poor, giving them a head start on social distancing as the virus spread.” They found these trends across the nation, including in the 25 largest metropolitan areas.

While the well-off are also more able to order grocery deliveries to avoid physically going to the supermarket, most of the 42 million Americans who are part of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program are unable to use food stamps to order their groceries online. They are being forced to risk their health by going to the store in person to be able to put food on the table for their families, reports Liz Crampton for Politico. Only six states currently allow those in the program to purchase food online, as difficulties can arise with regards to elements such as verification and payment of delivery fees. Considering the almost inevitable jump in applications to join the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program in the near future as a result of the coronavirus recession, Crampton writes, lawmakers and activists are rushing to find workarounds. Even so, the situation provides yet another example of how low-income families are at higher risk during the pandemic than their wealthier counterparts.

For those parents who are able to work from home, the separation between work life and family life has been almost entirely eliminated. In the face of this new reality, writes Samantha Schmidt for The Washington Post, fatherhood has become more visible than ever. While fathers now have more involvement in their children’s lives and childrearing more broadly than preceding generations, mothers still take on more home life responsibilities than fathers, even when both parents work full time and even when mothers earn more than fathers. Maybe, posits Schmidt, this pandemic will shed more light on fathers as caregivers and the disparities in couples with regards to caregiving and chores.

The coronavirus outbreak is wreaking havoc on U.S. economic and social life as we know it, but maybe we can turn that into a good thing, opines The New York Times’ Editorial Board. While the pandemic has united us in some ways, it has also exposed the chasms that separate us and the strain that has been placed on our democracy and society over the past half-century due to growing inequality. And though Congress has taken some action to fight the effects of the new coronavirus, there is much more to do—and unfortunately, it is unclear whether there is enough political willpower to do so. Our country has historically emerged from its darkest periods stronger and more unified, the Editorial Board writes, and this crisis can provide an opportunity for us to build a more just, more free, and more resilient United States.

Friday figure

Figure is from Equitable Growth’s “The most exposed workers in the coronavirus recession are also key consumers: Making sure they get help is key to fighting the recession” by Christina Patterson.