Wealthier individuals receive higher returns to wealth

Wealth inequality has soared in the United States over the past three decades. Today, the top 1 percent own about 40 percent of the nation’s wealth, levels last seen during the Roaring Twenties. A growing body of research now suggests that those at the top not only own much more wealth, but also register higher rates of return from their wealth. Although there are conflicting findings on why the wealthy earn higher returns, these studies open the door to an important line of research that could give us insight into wealth inequality in the United States.

A recent working paper using Norwegian data shows that higher returns for wealthier individuals are persistent over time for the same individual and across generations—and not just because they are compensated for risk-taking. The paper (funded in part by Equitable Growth) by economists Andreas Fagereng of Statistics Norway, Luigi Guiso of the Einaudi Institute for Economics and Finance, Davide Malacrino of the International Monetary Fund, and Equitable Growth grantee Luigi Pistaferri of Stanford University studies individual returns to wealth over the entire wealth distribution, both within and across generations.

The authors use 12 years of tax records on the wealth and capital income of all taxpayers in Norway from 2004 to 2015. These exhaustive tax records are available in Norway because of a wealth tax that requires assets to be reported—often done by employers, banks, or other third parties, thereby reducing errors that arise from self-reporting. The authors also are able to match parents with their children, and thus look at intergenerational patterns in returns to wealth.

Individuals earn substantially different returns on their wealth. The four co-authors find 3.8 percent average returns on overall wealth (financial assets plus housing minus debt) with a standard deviation of 8.6 percent. The difference between the average return at the 10th percentile and 90th percentile of overall wealth is about 18 percentage points. Given that Norwegians in the bottom 20 percent of their nation’s wealth distribution have negative wealth—they have more debts than assets—the authors measure returns as a share of gross wealth to ensure that people with debt costs exceeding their asset incomes are counted as having negative returns.

Why do the wealthy get higher returns from their wealth? In part, it’s because they invest a higher share of their assets in the stock market and other risky assets, and therefore are rewarded for their risk tolerance with higher average returns. Wealthier investors also benefit from the scale of their wealth, for example, by using checking accounts that pay higher rates for larger deposits and buying financial advice that leads to higher returns—what the authors call “economies of scale in wealth management.”

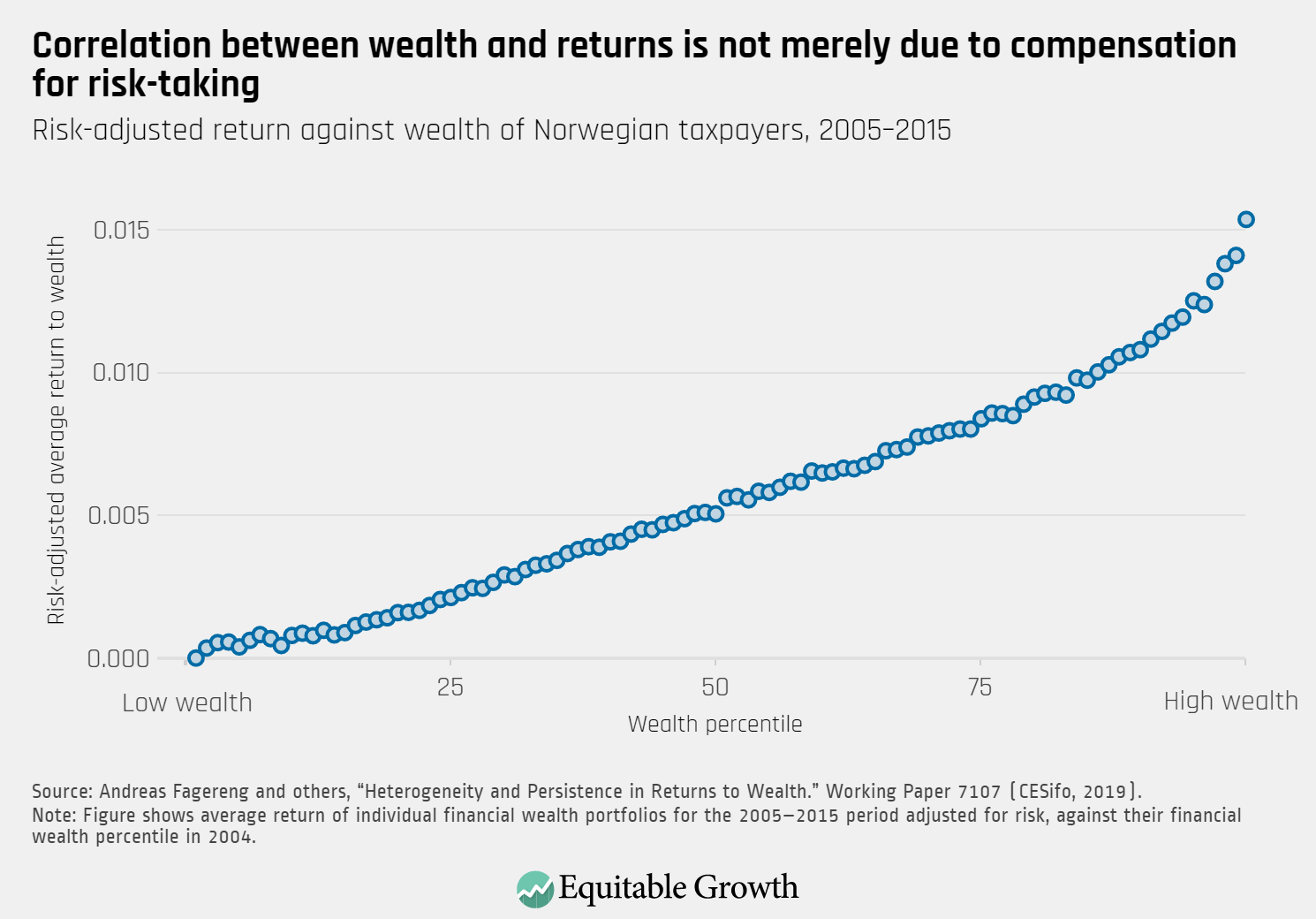

Yet the authors also find that risk compensation and scale, while important, are not enough to fully account for the variation in returns, or, in economic parlance, “return heterogeneity.” Bank deposit accounts are safe assets that bear essentially no risk. If return heterogeneity were explained by compensation for risk-taking, then there should be no variation in the returns that people get from deposit accounts holding the same amount of wealth. The authors find, however, that there is sizable heterogeneity: People with more education tend to deposit at high-return banks. Persistent variation in returns is therefore also explained, in part, by differences in financial sophistication and differences in ability to access and use superior information about investment opportunities. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

Returns to wealth persist across time when looking at the same individuals, but do they also persist across generations? The intergenerational transmission of wealth is well-documented: It is widely understood that the children of wealthy families are likely to have a lot of wealth as adults. The authors find that, like wealth, returns to wealth are correlated intergenerationally, though there are important differences in how returns to wealth accrue across generations.

At the top of the wealth distribution, the intergenerational correlation is higher, while at the top of the returns-to-wealth distribution, the intergenerational correlation is lower. So, a child of Amazon.com Inc. CEO Jeff Bezos will hypothetically own an extremely high level of wealth later in life, but will not generate returns from that wealth as high as did Bezos himself. In economic terms, those returns for Bezos’ child “revert to the mean.”

Some of the intergenerational correlation in returns to wealth is explained by scale dependence in wealth (higher levels of wealth getting higher returns), but correlation can also come from children imitating their parents’ investment strategies or inheriting traits related to risk preferences or talent in investing. Returns also are correlated when parents and children share a private business or they live close to each other and so earn similar returns on housing.

Compared to the United States, income is much more evenly distributed in Norway, but wealth is similarly concentrated. Another study by Laurent Bach at ESSEC Business School and his co-authors using Swedish administrative data also finds substantial heterogeneity in returns to wealth and a correlation between returns and level of wealth. These authors, however, find that the higher returns earned by the wealthy are compensation for taking higher systematic risk, not the result of exceptional investment skill or privileged access to information.

Even if the reasons behind the variation in returns to wealth have not yet been fully explained, these studies improve our understanding of how returns to wealth differ across the wealth spectrum. On the policy front, return heterogeneity could mean that a wealth tax would be more efficient than a capital income tax. Replacing a capital income tax with a wealth tax reduces the burden on high-return investors and thus may motivate more wealth accumulation. But a wealth tax might also widen the disparities in rates of return.

An ancillary benefit of a wealth tax in the United States would be the collection of more accurate data to estimate and track the wealth of the wealthiest Americans—just as the Norwegian wealth tax enabled Fagereng and his co-authors to do their data-driven research. Their findings are an important contribution to the empirical literature on the variation in returns to wealth, which can help policymakers understand the trends and dynamics of the extreme concentration in wealth and design policies that ensure that wealth disparities aren’t deepening generation after generation.