Competitive Edge: Structural presumption in U.S. merger control policy would strengthen modern antitrust enforcement

Antitrust and competition issues are receiving renewed interest, and for good reason. So far, the discussion has occurred at a high level of generality. To address important specific antitrust enforcement and competition issues, the Washington Center for Equitable Growth has launched this blog, which we call “Competitive Edge.” This series features leading experts in antitrust enforcement on a broad range of topics: potential areas for antitrust enforcement, concerns about existing doctrine, practical realities enforcers face, proposals for reform, and broader policies to promote competition. John Kwoka has authored this month’s contribution.

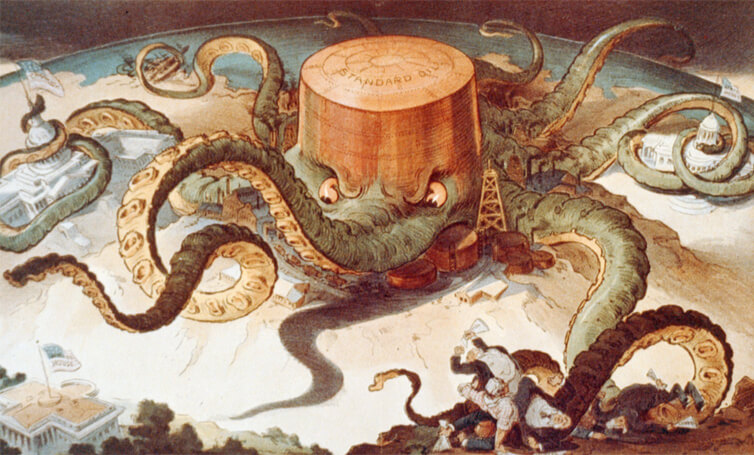

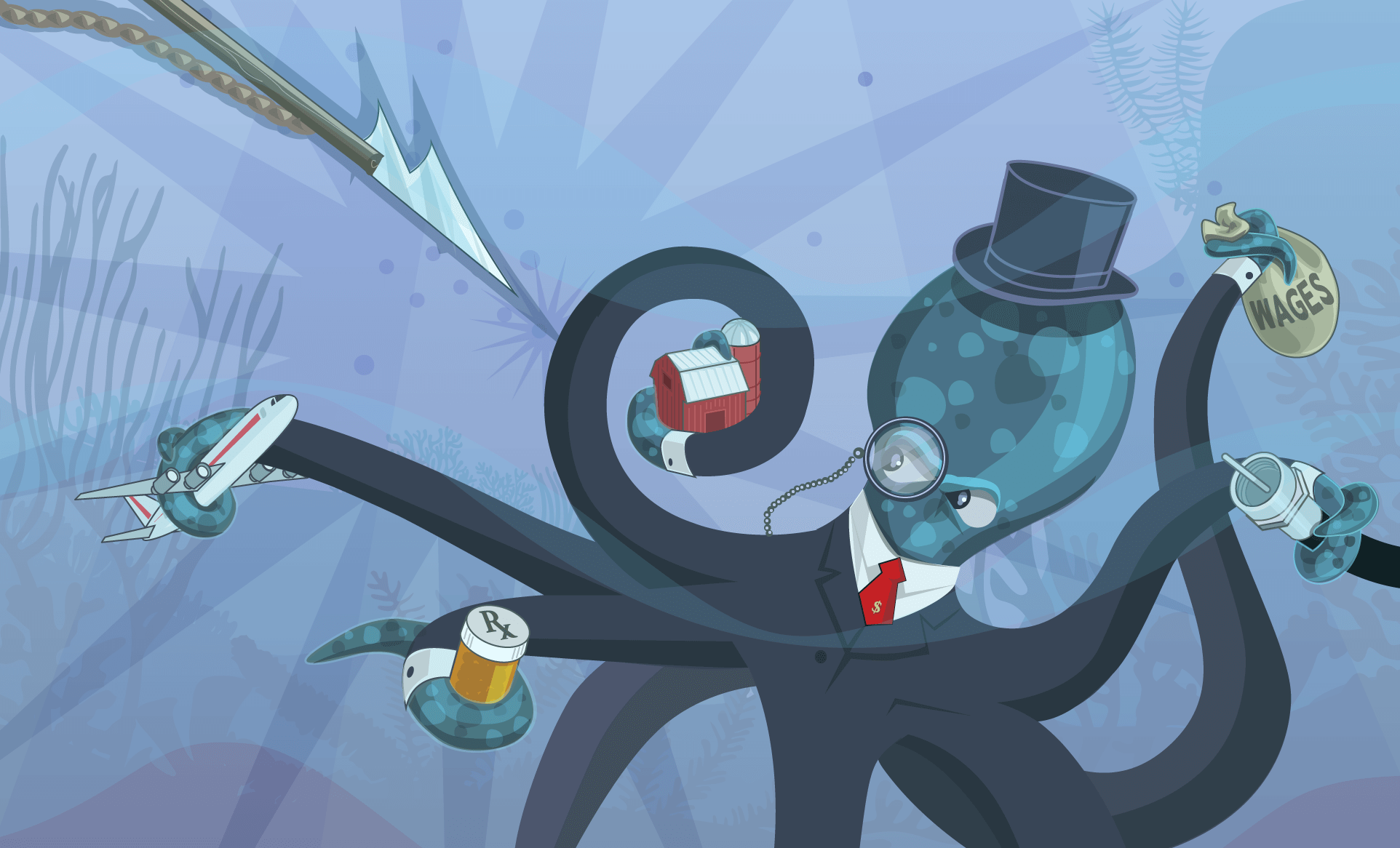

The octopus image, above, updates an iconic editorial cartoon first published in 1904 in the magazine Puck to portray the Standard Oil monopoly. Please note the harpoon. Our goal for Competitive Edge is to promote the development of sharp and effective tools to increase competition in the United States economy.

In remarkably short order, the discussion about competition in the U.S. economy seems to have arrived at the substantial consensus that a problem exists. True, there are some economists and policymakers who still want more evidence, and others for whom no amount of evidence is likely to suffice. But the reality that stares consumers in the face every day is diminishing choice in airlines, brewing, cable TV, dog food, eyeglasses, financial services, grocery stores, hospitals, and, yes, “the entire alphabet of U.S. industries.” This impression is corroborated by economywide data documenting the rising levels of market concentration, the reduced rates of entry of firms into the economy and the overall decline in the number of firms, and the above-normal rates of profit, especially for leading companies. And these forces, in turn, have been associated not only with higher prices and reduced choice of goods and services, but also with longer-term adverse effects on innovation and productivity, worker wages and income equality, and other social objectives.

The time has come to move on to the question of how to fix this problem of diminished competition. My own analysis, in “Reviving Merger Control: A Comprehensive Plan for Reforming Policy and Practice,” has identified several distinct weaknesses of merger control and proposes 10 changes in policy and practice that would help remedy it. Among these, one stands out as uniquely important because it would simultaneously make merger control more effective and more efficient. It would make it more effective by preventing a higher fraction of anticompetitive mergers and more efficient by relieving the antitrust agencies of some of their current burden of proof.

What is this seemingly magical policy potion? It is nothing more than restoring the 50-year-old legal doctrine known as the structural presumption. The structural presumption says simply that large mergers in highly concentrated markets are so likely to be anticompetitive that they can be presumed anticompetive unless proven otherwise. This proposition effectively shifts the burden to companies proposing to merge, so that they have to demonstrate why their merger is the rare exception to the general rule and will not harm competition. This contrasts with the current process, where the antitrust agency bears the full burden of predicting exactly how each merger—no matter how obviously problematic—will harm competition in order to act against it.

Reviving the old tool of structural presumption to strengthen modern merger control

The structural presumption doctrine was advanced by the U.S. Supreme Court in its 1963 decision in United States v. Philadelphia National Bank. In that ruling, the court noted that merger analysis is a difficult exercise in prediction and urged “simplify[ing] the test of illegality” in certain cases by “dispensing … with elaborate proof.” Specifically, the court stated that “a merger which produces a firm controlling an undue percentage share of the relevant market, and results in a significant increase in the concentration of firms … is so inherently likely to lessen competition substantially that it must be enjoined in the absence of evidence clearly showing that the merger is not likely to have such anticompetitive effect.” This doctrine reflected economic research at the time that showed a statistical relationship between high market concentration and prices or profit margins. It was intended to ease the process of merger control in those cases where competitive harm was fully predictable, without requiring the same detailed analysis as otherwise might be necessary.

A clearer statement of policy could hardly be imagined. What remained was to set out the applicable thresholds of share and concentration, and to identify the possible factors that might offset the presumption. These should, in principle, be found in the Horizontal Merger Guidelines issued jointly by the the Antitrust Division of the U.S. Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission. Reality differs. The share and concentration thresholds for mergers in those guidelines do not constitute a true presumption but rather, simply varying degrees of scrutiny. In addition, the relevant thresholds have twice been relaxed, exempting ever more mergers from the highest level of scrutiny—and, in any event, mergers exceeding the stated thresholds are often approved.

This last point—the deviation of practice from policy—is clear from Federal Trade Commission data on the number of merger investigations and the number of challenges made by that agency from 1996 through 2011. These data show that for mergers in markets with more than four remaining significant competitors—which, the FTC suggested, might be one with at least a 10 percent share—the FTC has challenged an ever-smaller fraction over time. The agency challenged more than one-third of mergers with five to eight such firms in the period 1996 to 2003, but only one-sixth in 2004 to 2007, and then literally none—zero—starting in 2008.

While the agency continued to challenge mergers in the very highest category of concentration, all mergers—every single one in this medium-to-high-concentration group—were nonetheless approved. This evidence leaves little doubt that weakened antitrust policy has contributed directly to rising concentration.

Of course, some commentators would argue that this narrowing of enforcement has been desirable because it has avoided making the mistake of challenging beneficial mergers. But as noted, economic research has long documented the effect of high market concentration on prices. In addition, there is now even more compelling evidence that mergers in these high-to-moderately-high concentration markets are, in fact, generally anticompetitive. This evidence comes from so-called merger retrospectives—careful economic studies of the actual price outcomes of specific mergers. I have matched the price outcomes of about 40 of these studied mergers to their market concentration. While this is only a small fraction of all such mergers, the evidence tells two strikingly different stories.

First, it shows that of these mergers with four or fewer remaining firms, prices did, in fact, rise in all cases. This provides support for the FTC’s strong—but not quite perfect—enforcement record against mergers in the highest concentration range. But the data also show that all mergers with five remaining competitors proved to be anticompetitive. The same is true for 80 percent of those with six remaining competitors and even for 50 percent of those with seven remaining competitors. Mergers, in short, prove to be anticompetitive in a significantly wider array of cases than the narrower set most recently targeted by the FTC.

The key and crucial discrepancy between enforcement and effects arises for mergers in high-to-moderately-high concentration markets, where there remain five, six, or even seven significant competitors. Here, enforcement has ceased despite clear evidence of competitive harm. To be sure, the failure of enforcement in this range is due to several factors, not all of which are within the control of the agency. The annual budgets of the two antitrust agencies are demonstrably inadequate for their mission. The judiciary is demanding ever greater proof of predicted anticompetitive outcomes. Ideological forces outside the agency have fostered an anti-antitrust view. Regardless of all the causes, however, antitrust policy has narrowed its mission and left a range of demonstrably anticompetitive mergers free to proceed.

A solution hiding in plain sight

Fortunately, a key initiative that would help to solve this problem is hiding in plain sight, suggested by the same data just used to identify the failure of merger enforcement. It is nothing more than the approach urged by the U.S. Supreme Court more than a half-century ago. After all, if all or nearly all mergers with fewer than some number of remaining significant competitors are known to be anticompetitive, that bright line standard—the structural presumption—could be used to prohibit them, absent some compelling reason, precisely as the Supreme Court urged. The evidence just reviewed makes clear that this would not result in excessive enforcement but rather would correct recent underenforcement.

Since the structural presumption originated with the court, it breaks no new legal ground. Nonetheless, new legislation to codify the presumption would strengthen the hands of the Antitrust Division of the Justice Department and the FTC in their use of the doctrine. In addition, more economic research into the best measures and thresholds of concentration would be important. And there are some practical hurdles to overcome. Specific “antitrust markets” would need to be defined. Characteristics of a “significant competitor” might need to be further specified. Potentially offsetting factors would need to be identified—and sharply circumscribed. And the courts would have to learn, or relearn, this doctrine.

A further advantage of structural presumption is that it would restore vitality to merger analysis concerning coordination among firms. Agencies have struggled with such cases due to the difficulty of proving that a particular merger crosses some line of predictable anticompetitive effects. But the very essence of the structural presumption is that beyond some small number of firms, coordination is, in fact, fully predictable, and therefore antitrust action is fully justified. This presumption would provide the crucial necessary tool for the agencies to bring and prevail in such cases.

So, based on the best current evidence, it would seem that an appropriately designed structural approach that shifts the burden for mergers with as many as five or six remaining competitors would be both effective and efficient. Such a policy would be effective since it would appear to make few errors, and whatever errors it might make would likely be offset by correcting the errors of inadequate current policy. It would be efficient since it would spare the antitrust agencies the burden they currently face of developing detailed, case-specific analyses of the mechanism for coordination and the dollar value of harms, buttressed by evidence from documents, data, and economic models. While all those might be necessary and feasible in some cases, recent antitrust cases show how the complexity of this process can result in bad court decisions. Moreover, avoidance of this burden would free up the agencies’ resources and allow them to bring more cases where enforcement has languished.

Merger analysis in recent times has benefitted from cutting-edge advances in economic models and methods, such things as unilateral effects and upward pricing pressure, diversion ratios and critical loss assessment, and others. But for the next—and necessary—step toward strengthening merger control, antitrust should look backward, back to the method provided by the U.S. Supreme Court for proceeding against mergers where case-specific evidence is difficult to assemble but the anticompetitive effects are nonetheless clear. Modern merger control can significantly improve enforcement by reviving the use of the structural presumption.

—John Kwoka is the Neal F. Finnegan Distinguished Professor of Economics at Northeastern University.