Vir illustris Martin Feldstein starts by saying: downward nominal price stickiness is such a thing that we do not have to worry about deflationary spirals in consumer prices. I agree. But I do not understand where his argument ends up:

…But is this a real problem?… Fortunately, we have relatively little experience with deflation to test the downward-spiral theory…. [Perhaps] they are concerned about the loss of credibility implied by setting an inflation target of 2% and then failing to come close to it…. [Perhaps] are actually more concerned about real growth and employment, and are using low inflation rates as an excuse…. [Perhaps they] want to keep interest rates low in order to reduce the budget cost of large government debts. None of this might matter were it not for the fact that extremely low interest rates have fueled increased risk-taking by borrowers and yield-hungry lenders. The result has been a massive mispricing of financial assets. And that has created a growing risk of serious adverse effects on the real economy when monetary policy normalizes and asset prices correct.

I certainly agree that deflation in consumer prices is not a thing, in our modern age at least–that what we have to worry about is deflation in asset prices. I said so back in 1999: http://www.brookings.edu/~/media/projects/bpea/spring-1999/1999a_bpea_delong.pdf.

But the rest of Feldstein’s argument–that it is important to raise interest rates now because their is a “massive misplacing of financial assets” with “increased risk-taking by borrowers and yield-hungry lenders” simply does not seem to compute at all. People like the estimable Gabriel Chodorow-Reich who have looked for that increased risk-taking have found little of it: http://www.brookings.edu/~/media/projects/bpea/spring-2014/2014a_chodorowreich.pdf. Real companies with real earnings and real businesses are not selling out outsized valuations. Equity earnings yields are–still–not notably high. The Standard and Poor’s yield is above its average over the past twenty years:

The assets that seem to be overpriced are those that offer nominal safety in reserve currencies issued by independent central banks with low inflation targets–and those are, overwhelmingly, the liabilities of governments and not of private sector entities. Goldman Sachs and its clients simply cannot issue a AAA bond these days.

Restoring the configuration of asset prices to anything like normal would, therefore, seem to me to not call for an increase in safe short-term interest rates above their current values, which correspond to a reasonable interest-rate feedback rule. Restoring the configuration of asset prices to anything like normal seems to me to call for:

- Raising the inflation target to 4%/year to greatly diminish the risk of again running into the zero lower bound.

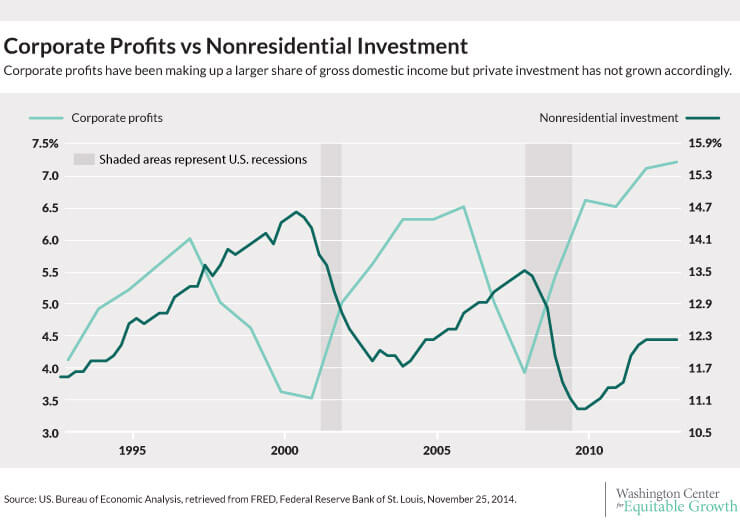

- Having governments create more of the safe nominal reserve-currency assets for which financial markets have such huge demand–which means for the governments to issue debt and spend on infrastructure.

And maintaining fiscal policy at its present configuration while raising short-term safe interest rates seems to me definitely not the way to get there…