Women’s History Month: U.S. women’s labor force participation

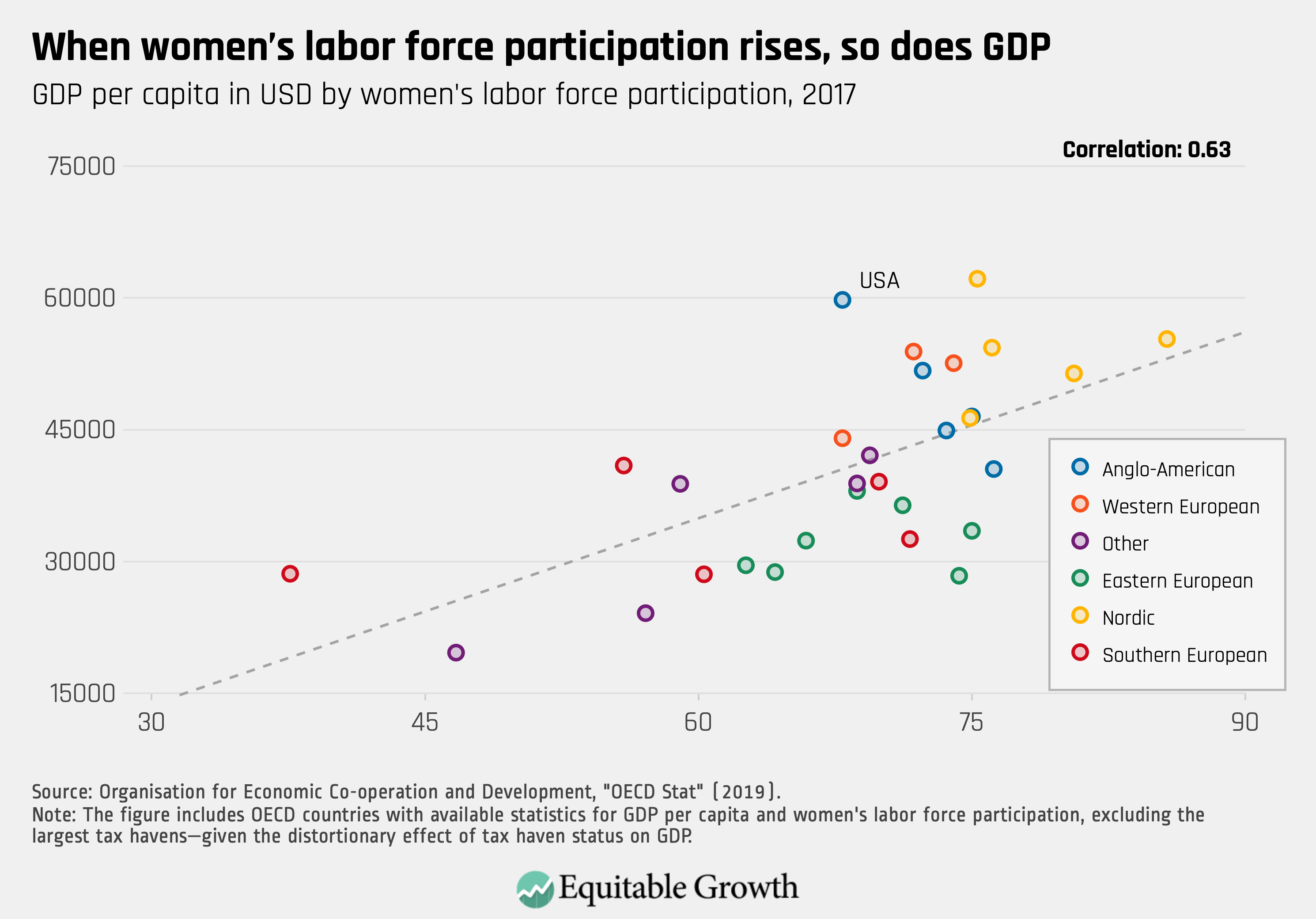

It’s Women’s History Month in the United States. What better time to discuss a key economic dynamic that both reflects and contributes to women’s changing role in American society than their advances in the workplace? Specifically, how has women’s labor force participation rate—the percentage of women engaged in the formal labor market by being employed or looking for work—changed over time? It’s an important issue. When women join the labor force, economies tend to grow more. Indeed, there is a significant relationship between a country’s per capita Gross Domestic Product and women’s labor force participation rate. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

For women in the United States, labor force participation rates have not followed a straight path. It has been a complicated narrative, deeply affected by women’s family roles, by discrimination, by the changing economy, by technological change, and by their own choices. And it is a continuing story, with surprising twists that economists continue to explore.

In a sense, this story begins with its first twist, in the 18th and 19th centuries. To be clear, this is a twist for us today, not for those who experienced it. From our modern perspective, we might assume that significant participation by women in the workforce was practically nonexistent until it began rising gradually in the 20th century. We would be wrong. A number of economists, and especially Claudia Goldin of Harvard University, have shown that women in the 18th and 19th centuries played a considerably more important role in the economy than we might have thought. They were critical to their families’ economic well-being and their local economies, not in their rearing of children or taking care of household responsibilities but by their active participation in growing and making the products that families bartered or sold for a living.

But eventually, as the production of goods became mechanized and moved outside of the home, women’s role in the market economy receded, and their labor force participation dropped substantially to its nadir near the end of the 19th century. Gradually, beginning after 1890 and very much into the 20th century, women had a growing place in the workforce. This path—declining from a high point in previous centuries, prior to the manufacturing economy, and then rising as the economy and society change over time—graphs as a U-shaped curve. One of Goldin’s most significant contributions was to show that the U-shaped curve applied to the development of economies worldwide, though, as Boston College economist Claudia Olivetti has shown, the dip is less significant for economies that began significant development after 1950. (For an illustration of the global nature of this phenomenon, see this graph created by the IZA Institute of Labor Economics.)

Goldin cites four periods after the nadir of women’s participation in the labor market, the first three of which she terms evolutionary and the final one revolutionary. In the first of these phases, from the late 19th century to the 1920s, it was primarily poor, uneducated single women who entered the workforce, often as piece workers in manufacturing or as employees in other people’s homes. Married women largely stayed home, and the single women who worked generally exited the workforce upon marriage. In the 1910s, we see more women working in teaching and in clerical positions, which began a period of major growth.

From the 1930s to the 1950s, Goldin’s second phase, married women entered the workforce in significant numbers, their rate rising from 10 percent to 25 percent. She notes that while 8 percent of employed women in 1890 were married, that figure rose to 26 percent in 1930 and 47 percent by 1950. These increases were the result of the rise of offices requiring clerical workers and new information technologies, along with tremendous growth in the number of women attending high school in the early 20th century. It’s worth noting that women’s workforce participation was negatively affected by their husbands’ income. The higher his income, the less she would “need” to work outside the home. But that began to change during this period.

In the next phase, according to Goldin, women’s labor force participation, driven by married women, rose substantially. And it continued to become more common for married women to continue working even as their husbands’ income rose. One reason that married women worked more was the growing availability of scheduled part-time employment. In addition, societal barriers, and in some case legal barriers, to married women continuing to work were dropping.

Finally came what Goldin calls “the quiet revolution,” the period from the late 1970s up to the very early 21st century. In this era, women’s overall labor force participation rate rose but not by all that much. What did happen, however, was that the percentage of women of childbearing age with a child under the age of 1 in the workplace rose dramatically, from 20 percent to 62 percent. What Goldin refers to as the revolution are these changes: Young women in their late teens during the 1970s altered their “horizons” (their career expectations) so that they anticipated long, continuous careers that would not be cut short by marriage and children. This development, in turn, encouraged them to invest more in their education, with increasing numbers going to college and beyond, thus preparing them for careers that gave them status closer to men in the workplace.

At the same time, women began postponing marriage and childbearing. This was almost certainly, as shown by Goldin and by the University of Michigan’s Martha Bailey and her co-authors, due in part to the introduction and growing popularity of the birth control pill, the reliable contraceptive that gave women more control over the timing of childbearing. The pill had the effects of both increasing female labor force participation and narrowing gender pay inequality. And women began to see their lives and their identities differently, with their professional selves becoming as important as their families.

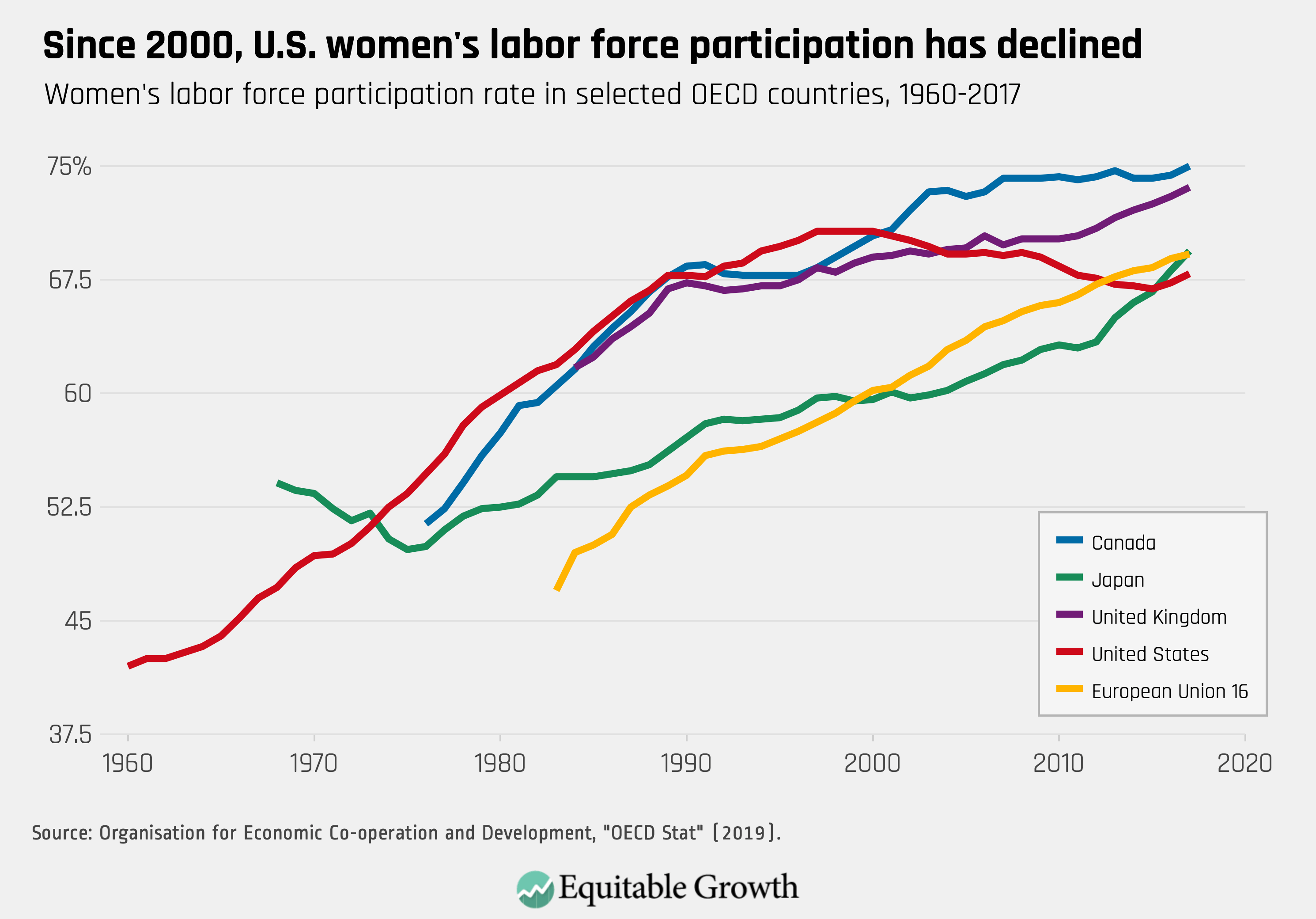

And then something else happened. Beginning around 2000, the advances in women’s labor force participation stopped. The rate flattened and then began to decline. To be sure, the decline is relatively small, a few percentage points, but it is real and it is unique among developed countries, according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

We still don’t know the reasons for this reversal, but we have some clues. Sandra Black of the University of Texas at Austin and her co-authors note that men’s labor force participation rate has been declining for several decades. Until 2000, this caused a significant, though not nearly complete, convergence between women’s and men’s labor force participation rates. Since 2000, however, the relative decline for women has actually outpaced that of men. Between 2000 and 2016, prime-age women’s labor force participation fell by 4.2 percent, from 78 percent to 74 percent. During the same period, prime-age men’s labor force participation fell by 3.7 percent, from 91 percent to 88 percent. The decline in men’s labor force participation is a trend generally attributed to poor labor market opportunities, particularly for low-skilled men. A question, therefore, is whether women’s rate began to decline for the same reason. Some evidence points in that direction, but the story is not necessarily a simple demand-side tale.

As previously noted, this decline in women’s labor force participation is not replicated in other OECD economies, where the rate continues to rise. Black and her co-authors point out that while the U.S. labor market is among the most flexible in its ability to accommodate changes in technology and other factors that change the nature of work, it is also among the least supportive in providing unemployment, job-search, and training benefits that could help both men and women adjust to change.

Those researchers also point to the potential positive impact of implementing paid family leave and expanded access to childcare on prime-age women’s labor participation rates. It is clear from recent research by Olivetti and Barbara Petrongolo of the London School of Economics that national family policies can have a significant positive impact on women’s labor force participation. The researchers examined family policy across high-income Western European countries, Canada, and the United States. What they found was that investments in childcare and early childhood learning had significant impacts on women’s labor force participation. They also found a positive impact, though less pronounced, for maternity leave policies of up to 50 weeks. Interestingly, separate research finds that family policies that benefit only women can undermine their potential impact, as they might affect employers’ attitudes toward female employees.

Unfortunately, what the OECD has also reported is that as of 2012, the United States ranked 33rd of 36 countries in investing in early childhood care and education, relative to overall income. This country is also the only developed country without a national paid leave program.

Another promising area for legislation to support women’s ability to participate in the workforce is scheduling stability. Over the past decade, researchers have documented instability and unpredictability in the schedules of retail workers, and they are increasingly showing that providing greater stability and predictability for schedules can not only improve employer profits and strengthen the economy but also improve the health of their workers.

It seems clear that a change in direction for U.S. policies related to childcare and early education, along with a strong national paid leave policy for family leave could help to reverse the downward trend of U.S. women’s labor force participation and put it back on the same path that most other developed countries are on. We have seen that while the 20th century saw a restoration of women’s strong participation in the workforce, the 21st century has seen a disturbing reversal. Policymakers can do something about this, and it would benefit families and the nation’s economy.