Will labor’s surging popularity result in new union members in the United States?

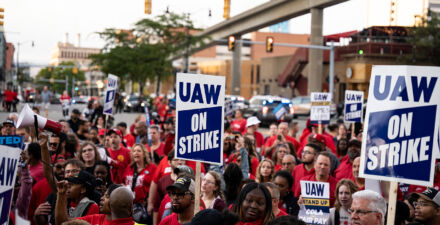

Mass strikes across U.S. industries, successful organizing drives in multiple sectors of the economy, and a U.S. president who declares himself proud to be labeled “the most pro-union president in history” all point to a historic resurgence for organized labor in the United States. Even longtime foes of unions have begun to rethink past positions in the wake of evidence showing labor unions’ growing popularity among Americans.

Yet organized labor’s rise isn’t apparent in the number of unionized U.S. workers, which continues to decline. In 2023, the unionization rate fell to just 10 percent, a historic low, and just half of what it was in the early 1980s. The core issue driving these low membership rates is the difficulty of organizing at scale in the private sector, where just 1 in 20 workers belongs to a union. There is no ready solution to this obstacle, absent a highly unlikely reimagining of the National Labor Relations Act, the federal law governing labor relations in much of the U.S. private sector.

As we approach Labor Day, though, the good news for organized labor is that there is a large section of the workforce that isn’t governed by the NLRA—and one that has proven easier to organize: the public sector. Just less than one-third of workers in the public sector belongs to a union today, and new evidence suggests that number should remain stable—or even could increase substantially—helping to reverse labor’s slipping share of the overall U.S. workforce.

Earlier this year, I, along with my colleagues Patrick Denice of Western University and Jennifer Laird of Lehman College, surveyed 4,000 full-time public-sector workers. We asked them a range of questions about their attitudes toward labor unions, their experiences in unions (among the members in our sample), and their interest in joining unions (among the nonmembers).

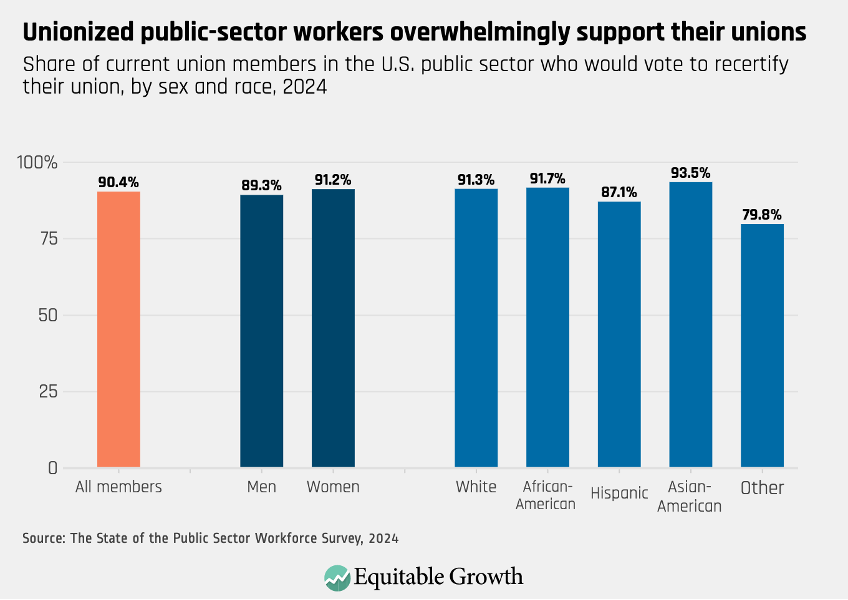

The first encouraging sign for labor union organizers from our survey is overwhelming support for unions among the ranks of the organized. Among the members in our survey, 94 percent reported that unions were essential or important. When asked if they would vote to recertify their union, 9 in 10 current members said yes. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

This is critical information in the wake of the 2018 U.S. Supreme Court case, Janus vs. AFSCME. This ruling effectively made the entire public sector “right to work,” which allows workers to opt out of paying dues but still retain the benefits of collective bargaining in unionized workplaces. The concern for unions is that right-to-work laws incentivize workers to free ride—to enjoy the benefits of union representation without bearing any of the costs—weakening a union’s power. Overwhelming support for their unions should help alleviate unions’ concern about public-sector workers dropping their memberships in the post-Janus landscape.

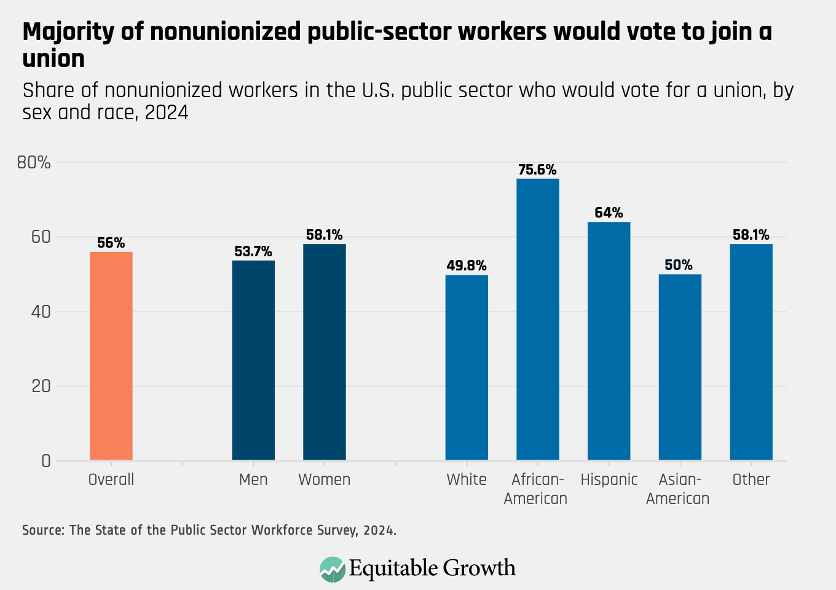

Among unorganized workers in our sample, more than two-thirds said that unions were either “essential” or “important,” while less than one-third said unions were something they could do without. Yet expressing general support for unions is not the same as wanting to join one. Taking a cue from past surveys of predominantly private-sector nonunion workers, we asked public-sector nonunion workers whether they would vote for a union if given the opportunity. In no prior survey has this “unmet demand” for representation exceeded 50 percent—until ours.

We find that 56 percent of unorganized workers said they would join a union. And, echoing recent research that finds African American men and women in the public sector disproportionately benefit from union membership, the desire to join a union is highest among women and African Americans. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

Past surveys of predominately private-sector nonunion workers also find a sizeable number of workers eager for union representation, albeit a smaller fraction than in our survey. And yet this unmet demand has not translated to private-sector union growth. So, why should we expect anything different in the public sector?

First, despite much higher public-sector unionization levels than private-sector membership rates in the United States, the number of U.S. public-sector unionized workers remains considerably lower than in peer nations. In Canada, for example, three-quarters of the public sector belongs to a union; in the United Kingdom, nearly half do. The United States, at about one-third, can clearly grow more, at least in the comparative context.

Second, our data suggest the unmet demand for union representation is not concentrated in states hostile to public-sector collective bargaining. Unlike in the private sector, there is no federal law governing public-sector labor relations. Instead, states have enormous leeway in granting or restricting collective bargaining among government employees, resulting in a patchwork of labor relations. They range from states such as South Carolina, where collective bargaining between public-sector workers and the state is prohibited, to New York, where it is required.

Our data indicate that the unmet demand is actually higher in states with the most pro-union legal frameworks. These findings are surprising. We expected a smaller share of the public-sector nonunion workforce to desire union representation than among private-sector workers, and we expected demand to be concentrated in states where the barriers to entry were formidable. Instead, we found the opposite.

Finding so much unmet demand for unionization in pro-union states should buoy organizers eager to find ripe targets for union representation. Combined with the high levels of support for their unions among existing public-sector union members, these results suggest there is a pathway for unions to stem further erosion in membership—they just need to know where to look.

Did you find this content informative and engaging?

Get updates and stay in tune with U.S. economic inequality and growth!