What kind of labor organizations do U.S. workers want?

Looking at trends in union membership over the past 30 years, you might assume that U.S. workers have soured on the labor movement. But given a politically hostile environment toward unions and an increasingly fissured workplace that has broken down traditional employment relationships and norms around workplace fairness, it’s not surprising that private-sector membership in unions steadily declined from nearly one-quarter of all workers in 1973 to barely 6 percent in 2018.

Yet when my colleagues William Kimball and Thomas Kochan at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Sloan School of Management and their co-authors asked nonunion workers in 2017 what they think about unions, it turns out that nearly one-half of them—48 percent—would vote to form a union at their job if given the opportunity to do so. That figure was up from about one-third of respondents in surveys from 1977 and 1995.

Clearly, a large portion of the U.S. workforce wants some form of union representation on the job. But under current labor laws, which were written for a previous era of employment and industrial organization, and with variable enforcement practices based on political climate, it seems very unlikely that the vast majority of those workers will ever have the opportunity to vote for a union. The outdated legal structure governing U.S. labor unions is increasingly mismatched to our economy, with the result that workers wishing to exert their rights to organize face greater barriers, perhaps unmatched since the enactment of the National Labor Relations Act in 1935.

With the ability to form and maintain effective unions becoming more theory than reality for tens of millions of U.S. workers, labor policy experts, union leaders, and politicians (including some 2020 Democratic candidates) are proposing a complete overhaul of labor law. This raises an important question: If we were creating unions from scratch, what kind of system would workers want? What would they want unions to look like?

In ongoing research with my colleagues Kimball and Kochan, we are trying to answer that question. We have fielded surveys of U.S. workers to probe the features of hypothetical labor organizations that they find most appealing. Drawing on conjoint analysis, a survey method originally developed for marketing research, we presented more than 4,000 workers with pairs of labor organizations containing a variety of dues, features, benefits, and services. We then asked respondents to indicate their likelihood of joining each labor organization, as well as the maximum amount in dues they would be willing to pay.

Some of the features we tested in our surveys correspond to traditional union functions, such as collective bargaining and mandatory dues for all members. Other features are present in the U.S. labor movement but are not widespread—among them, systems of portable health insurance and retirement benefits that workers can take from job to job. And still other features we tested are not present in the United States, including union representation on corporate boards of directors (known as co-determination) or unions that collectively bargain on behalf of an entire industry or state rather than simply for workers at a single business (known as sectoral or regional bargaining).

In all, we varied nine different attributes of the labor organizations we presented to survey respondents. So, for example, one organization we presented to workers might have the following characteristics:

- Be open to all current workers at the business or organization, regardless of job

- Engage in collective bargaining on compensation, hours, and working conditions on behalf of all workers in the industry within a region

- Provide health and retirement benefits

- Have mandatory dues only for workers who receive benefits from the organization

- Offer workers opportunities to work with management to recommend improvements in how workers carry out their responsibilities

- Offer legal representation to workers with common nonworkplace legal problems

- Represent workers in a joint committee with top management to decide how the organization should operate

- Never use the threat of strikes

- Campaign for pro-worker politicians

While the other organization would be described as follows:

- Be limited to workers in a particular occupation at their workplace, but allow them to stay as members when they leave their job

- Engage in collective bargaining only for dues-paying members at that workplace

- Offer training to keep skills up to date

- Have mandatory dues for all

- Not get involved in how workers do their work

- Offer legal representation only for workplace rights issues

- Have a position on the board of directors

- Include the threat of strikes in its arsenal

- Advocate on behalf of worker-related public policies but not candidates

The number of respondents and the conjoint design of our survey enabled us to determine which specific qualities workers would value most (and least) in a union and how much they would be willing to pay in dues for such organizations.

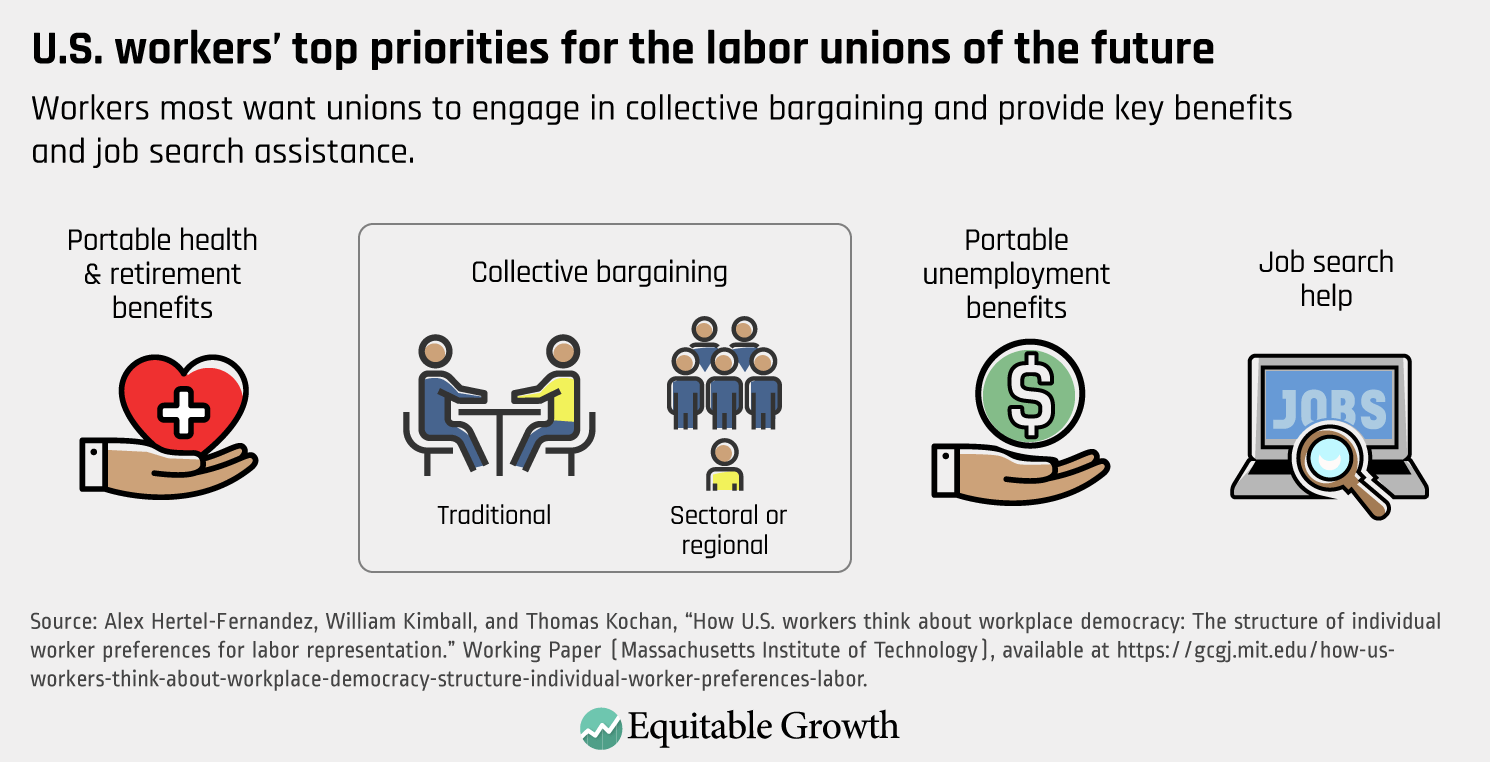

The most striking finding from our research was just how consistent workers of different ages, with different skills, from different industries, and in different occupations were in their preference for a common set of labor organizations. Workers were most likely to say that they would join and pay dues to labor organizations that offered some form of collective bargaining and that offered them portable health insurance, retirement, and unemployment benefits across jobs, training for current and future positions, legal representation for common workplace and nonworkplace issues, and input into management decisions about how they did their jobs and how their company operates. The most potent of these were collective bargaining and providing health, retirement, and unemployment benefits. Collective bargaining was such a high priority that both the firm-based negotiations that occur under current U.S. law and sectoral bargaining, which does not, were among workers’ top five selections. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

Some of the attributes workers want are things that unions generally do now. Collective bargaining, for example, is obviously a mainstay of today’s unions. But while some unions manage health plans and retirement benefits across employers, such arrangements are not widespread. Moreover, unions do not currently have a role in administering jobless benefits (as is the case in some Western European countries). And formal participation in deciding how a company is managed is neither required nor protected by the National Labor Relations Act, limiting U.S. unions’ leverage in this area.

Policymakers wishing to modernize U.S. labor laws for the 21st century economy and workforce should ensure that unions can offer the benefits and services workers want and need. Compared to their counterparts in other rich democracies, U.S. labor unions are substantially constrained in what they can offer to workers—members and nonmembers alike. Our research suggests that labor law reforms can and should help unions give workers the representation they want in the workplace, both by specifically permitting unions to engage in certain activities and by opening the way to new kinds of representation. At a minimum, the U.S. Congress and the states should make it easier for workers to form and join unions. More ambitiously, Congress should amend the National Labor Relations Act to encourage the more expansive collective bargaining, social benefits provision, and input to management that workers indicate they find appealing.

The steep, long-term decline in union membership both reflects and contributes to the attenuation of worker bargaining power in the U.S. economy. It is without a doubt a factor in the rising income inequality since the 1980s. Many workers want to belong to a union, but for most of them, changes in the economy, the inadequacies of current labor laws, and the growing power of employers thwart that desire. Rewriting the law can play an important role in revitalizing U.S. workers’ ability to join and form unions. My colleagues and I will continue our research on what workers want in the unions of the future in the hope that we can not only learn more about what matters to workers but also ensure that policymakers have the evidence on which to base potential reforms.

—Alexander Hertel-Fernandez is an assistant professor of international and public affairs at Columbia University.