Weekend reading: What the 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances reveals about racial and economic inequality edition

This is a post we publish each Friday with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth published this week and the second is relevant and interesting articles we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

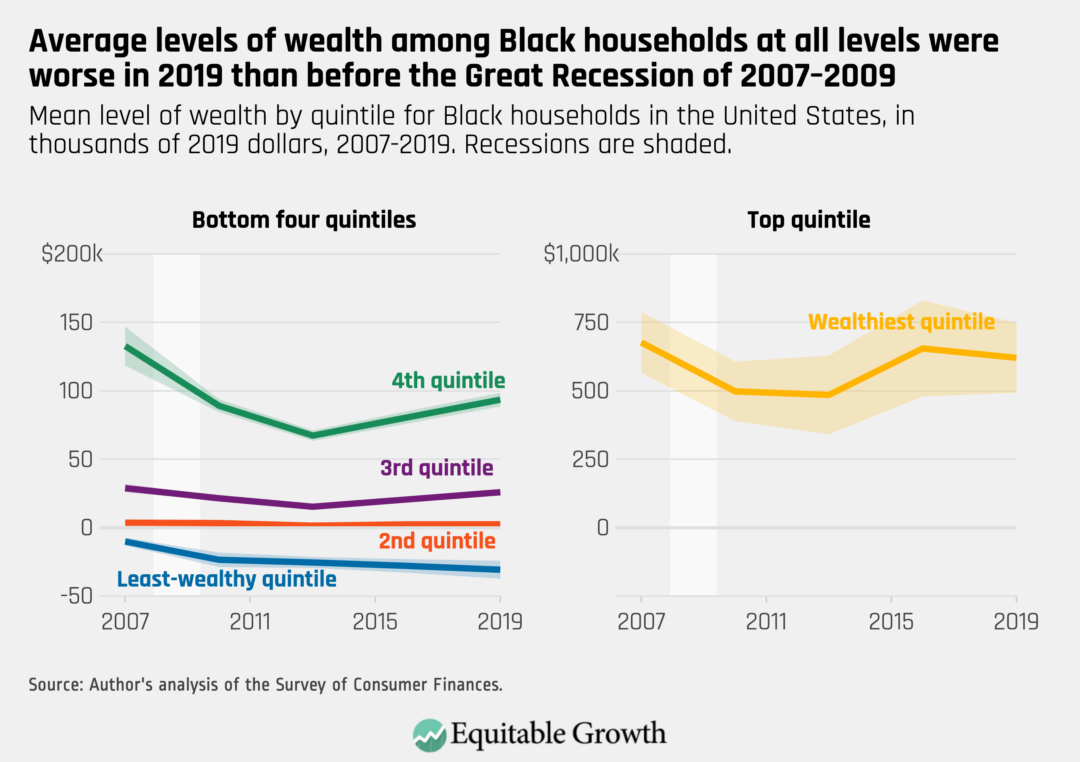

The Federal Reserve last week released its 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances, a triennial dataset on U.S. households’ financial situation. Austin Clemens analyzes the data and finds that over the more than 10 years of economic growth since the previous economic downturn, U.S. households barely recovered their prerecession levels of nonhousing wealth, and many are less likely now to own a home that could be leveraged as a financial asset. Clemens disaggregates the data by race, income, and educational level to show that Whiter, wealthier, and more educated households were much more able to recover their wealth than Black, Hispanic, lower-income, and less educated households. In fact, he writes, White households, on average, had 15 percent more wealth in 2019 than they did in 2007, while Black households had 14 percent less wealth and Hispanic households had 28 percent less wealth in 2019 than in 2007. This means that as the U.S. economy entered the coronavirus recession earlier this year, most families were in a worse position than they were at the start of the Great Recession to weather the economic storm. Clemens urges policymakers to act, and quickly, to avoid repeating the mistakes that led the last recovery to be sluggish and deepen existing inequalities.

One way of building wealth in the United States—outside of homeownership—is through savings for retirement. David Mitchell and John Sabelhaus review the 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances to specifically determine trends in retirement savings since the Great Recession of 2007–2009. They find that many U.S. households don’t have retirement savings, and, looking at a survey from May 2020, see that many of those who do have drawn on it this year to help them remain afloat during the coronavirus recession. After breaking down the data further by race and income, Mitchell and Sabelhaus reveal that almost two-thirds of Hispanic households and half of Black households don’t own a retirement savings account, compared to one-fourth of White families and fewer than one-tenth of high-income households. In fact, those families in the top 10 percent of the income spectrum have more in retirement savings than the bottom 90 percent combined. Mitchell and Sabelhaus offer several policy solutions to close the racial and economic divides in retirement savings coverage, including several ideas that have already been proposed by some policymakers.

The coronavirus recession drives home anew the importance and benefits of a strong Unemployment Insurance system across the United States to protect and support workers during economic crises. Alexander Hertel-Fernandez and Alix Gould-Werth explore the links between labor organizations and Unemployment Insurance in propping up workers’ voices and reducing disparities in applying to and receiving unemployment benefits. They find that labor organizations make it easier for workers to use unemployment benefits, narrowing racial and educational divides in UI applications and receipt. Hertel-Fernandez and Gould-Werth also show that workers who had better access to the UI system during this recession felt more comfortable engaging in workplace collective action, such as strikes for better working conditions or pay. The co-authors close with three important implications for public policy of this so-called virtuous cycle, in which greater access to unemployment benefits “supports workplace collective action, including forming labor unions, which, in turn, support greater access to unemployment benefits.”

Hertel-Fernandez and Gould-Werth also participated in the latest installment of Equitable Growth’s In Conversation series, in which they further discuss a wide range of topics related to Unemployment Insurance. They touch upon themes such as the current weaknesses of the UI system in the United States and five specific policy reforms to strengthen it, fiscal constriction’s role in hampering UI programs and access to unemployment benefits, the role of academics (and academics’ understanding of the lived experience of unemployed workers) in designing a better way of delivering Unemployment Insurance to those in need, and more.

Earlier this week, the U.S. Census Bureau released new data on the effects of the coronavirus recession on workers and households for the period between September 16 and September 28. Austin Clemens, Kate Bahn, Raksha Kopparam, and Carmen Sanchez Cumming put together a series of five graphics that highlight key trends in the data.

Links from around the web

Before the coronavirus swept through the U.S. economy and society, low- and middle-income earners were finally starting to see their wages rise, writes The Washington Post’s Tory Newmyer, who looks at the Census Bureau’s 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances. Yet despite average wealth slowly increasing alongside rising wages, the divide between the haves and the have-nots continued to grow wider after the Great Recession of 2007–2009. In fact, Newmyer continues, the top 1 percent owns around one-third of all wealth in the United States—close to a three-decade high for that group—while the bottom 90 percent of income-earners saw their wealth decline over the past 30 years. Newmyer looks at the effect of generational transfers of wealth, namely via inheritances, on the racial wealth divide, as well as the booming stock market, finding disparities in both of these areas by race and income.

In small tourist towns, the coronavirus recession is threatening local economies in unprecedented ways. Vox’s Terry Nguyen visits the city of Anaheim, California, which is home to Disneyland and whose economy revolves around the theme park’s success. But, as the park has been closed indefinitely to prevent the spread of the coronavirus and COVID-19, the disease it causes, small businesses in Anaheim have been hit hard and the city’s revenue has plummeted, leaving many to wonder whether any businesses will survive long enough to serve the millions of people who will return once the pandemic wanes and the park reopens. In the wake of Disney’s recent announcement that it will lay off 28,000 employees across its parks and in other corporate divisions, Nguyen writes, the fate of the city of Anaheim is tied to the fate of Disneyland. But, somewhat surprisingly, not all tourist towns are in the same dire position. Nguyen turns to Telluride, Colorado, and Sevierville, Tennessee—two small cities that are equally dependent on their local tourism attractions but have managed to stay afloat—in search of why some towns are struggling more than others.

If it wasn’t already clear that the coronavirus recession is hitting certain demographic groups harder than others, the latest employment data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics shines a harsh spotlight on the gender disparities of this recession. In fact, reports Stephanie Ebbert for The Boston Globe, four times more women than men left the labor force in September. Of the 1.1 million workers to drop out of the workforce, 865,000 were women, compared to 216,000 men. This discrepancy indicates that the burden caused by the child care crisis is being disproportionately carried by women, and reinforces many economists’ worries that women’s labor market gains over the past several decades are likely to be lost in this recession. The employment numbers also obscure the racial unemployment divides, Ebbert continues, with both Black women and Latina workers facing unemployment rates around 11 percent even as the overall joblessness rate for women is 7.7 percent.

Last week, California Gov. Gavin Newsom (D) signed a law establishing a taskforce to study the state’s role in the enslavement of Black Americans prior to the end of the Civil War and make recommendations about reparations. California at that time was a free state, Gillian Brockell writes in The Washington Post, yet many White southerners brought these enslaved workers with them during the Gold Rush beginning in 1848 and could keep them enslaved in the state until it was abolished nationally in 1865. Brockell tells a handful of California’s hidden stories about enslaved Black Americans, which will get renewed attention now, thanks in part to this first-of-its-kind law, which had bipartisan support in the state legislature. Though some critics argue that no state alone can fully atone for the original sin of our nation and society—that has to come from the federal government, they argue—whatever action the California taskforce decides to take could be a start, alongside a federal reparations program.

Friday figure

Figure is from Equitable Growth’s “New wealth data show that the economic expansion after the Great Recession was a wealthless recovery for many U.S. households” by Austin Clemens.