Weekend reading: ‘OK, boomer’ edition

This is a post we publish each Friday with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth published this week and the second is relevant and interesting articles we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

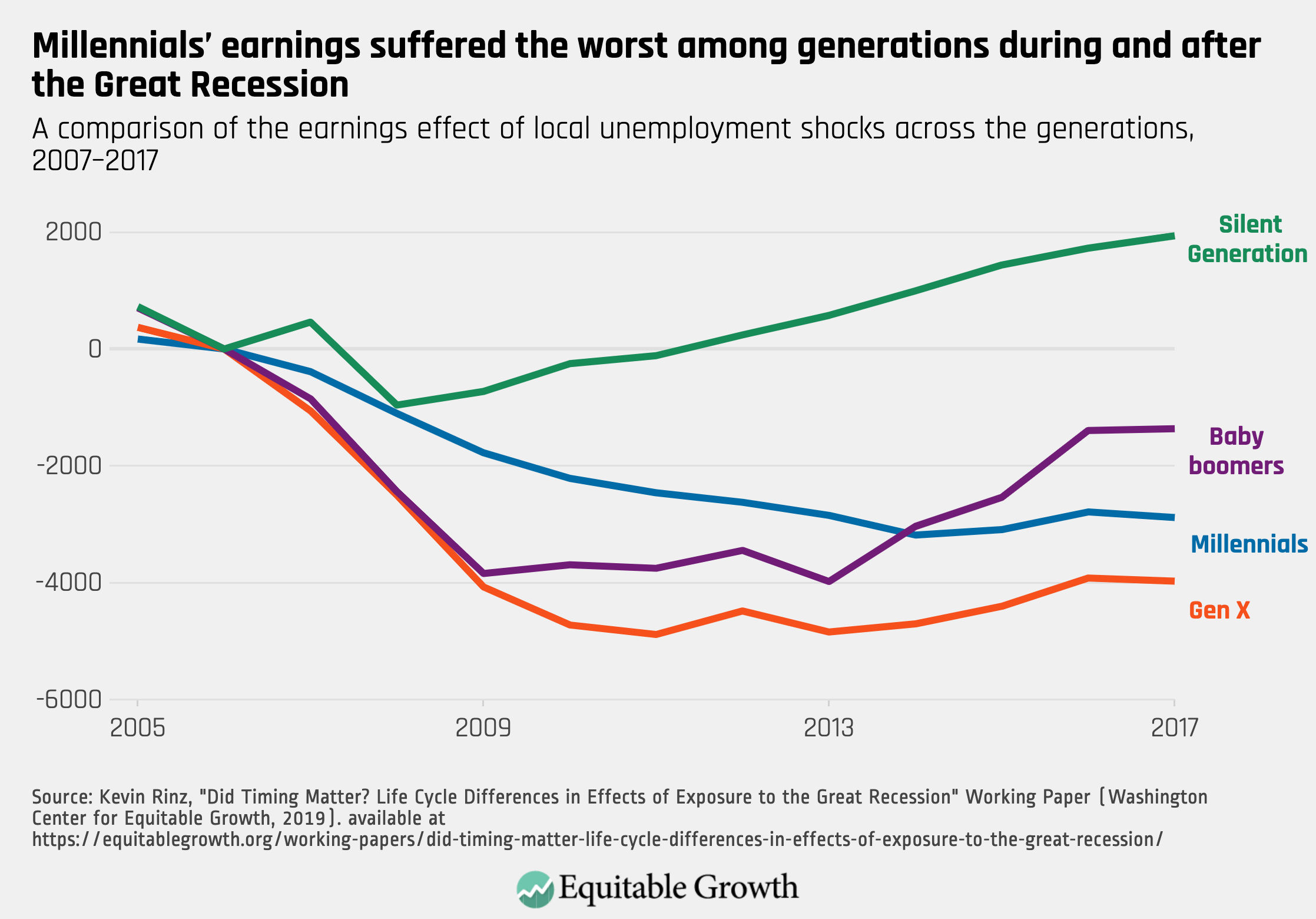

Apparently, the time for niceties between generations has come to a close with just two words: “OK, boomer.” The phrase is being thrown around like a new four-letter word on the internet, while new research from Equitable Growth shows that perhaps there’s an economic undertone to this latest intergenerational animosity: Millennial workers have not fared as well in the post-Great Recession period as other working-age groups. As Kate Bahn writes in a post about the research, local unemployment shocks during the Great Recession had a negative impact on the employment of all age cohorts, but millennials (defined as those born between 1980–1994) were the most negatively affected. Millennials’ earnings also suffered the worst during and after the Great Recession, compared to other generations, and they are less likely to be working for a high-paying employer today. These persistent negative outcomes for millennials demonstrate “how inequality reduces economic opportunity for those who have less to start with in terms of jobs and earnings” and how a tight labor market doesn’t necessarily translate into positive economic outcomes for all workers, writes Bahn.

Three recent reports—one from the Stigler Center, one commissioned by the United Kingdom, and one to the European Commission—examine antitrust and competition issues in the digital arena. Michael Kades discusses each report in detail, providing an overview of current digital market conditions, what that means for competition online, and potential remedies to some of the biggest issues facing digital market competition: the acquisition of nascent competitors and online platform discrimination. Kades writes that “a combination of antitrust enforcement and competition-enhancing regulations likely provides the best path forward to exploiting the benefits of these markets while limiting the dangers they pose for competition.” His column summarizes the paper about these three reports that he submitted to the American Bar Association’s Fall Forum.

Check out Brad DeLong’s latest worthy reads for his takes on recent Equitable Growth content and posts from around the web.

Links from around the web

A new study indicates that a higher minimum wage does not lead to higher unemployment, writes Dylan Matthews in an explainer on raising the wage floor for Vox.com. Matthews summarizes the recent research, which finds that “even if a few workers lose jobs, those costs are significantly outstripped by increased wages for workers who keep their jobs.” Matthews points out, however, that some economists remain skeptical, particularly regarding long-term effects on job growth and the level to which the minimum wage is raised. The disagreements and varying research results point to larger structural forces, Matthews concludes: “There are big monied interests opposed to minimum wage increases, and smaller but real monied interests (specifically unions) supportive of them.”

For all the talk of late about wealth taxes and fighting billionaires, writes Noah Smith for Bloomberg, you’d think the number of ultra-wealthy people had skyrocketed in the past few years alone. Wealth inequality has been high in the United States for decades, so Smith asks, where did all this class resentment come from? It probably has its roots in the bursting of the housing bubble, he argues, when the vast majority of the country lost everything they had been saving, but the wealthy largely made it through with barely a scratch. This immunity to financial setbacks highlights how rare it is these days for wealthy people to lose their fortunes just like the rest of us, Smith writes—and why policymakers looking to avoid class conflicts should support ideas that will help reduce financial risks for the middle class.

Republicans have now come up with a plan for paid family leave, which has long been a policy for which Democrats have fought. If both sides want it, then what’s the hold up? Claire Cain Miller of The New York Times’ The Upshot argues that the big divide between the two parties is over which workers would gain access to the paid leave, and where the money to pay for it would come from. Generally, she explains, Democrats want to create a new federal fund, financed by a payroll tax increase, that covers paid leave for new parents and workers needing time to care for their own serious illness or that of a family member. Republicans support using people’s existing Social Security benefits to cover leave for new parents and reducing the amount they’d then receive when they retire—essentially, treating Social Security like an individual account more than a larger social insurance fund. There have been a flurry of bills proposed in Congress, and the Trump administration has, so far, not taken sides on which one it will back. The administration, however, plans to host a summit on the issue at the White House next month.

Friday figure

Figure is from Equitable Growth’s “‘OK, Boomer’: How millennials have been left behind in the recovery from the Great Recession” by Kate Bahn.