Wealth taxation: An introduction to net worth taxes and how one might work in the United States

Overview

Increasing wealth inequality has spurred calls for the adoption of a federal net worth tax in the United States. This brief provides an introduction to net worth taxes, also referred to as wealth taxes. It summarizes how a net worth tax works, reviews the revenue potential of such a tax, and describes the distribution of the economic burden that would be imposed.

Download FileWealth taxation: An introduction to net worth taxes and how one might work in the United States

What is wealth?

A family’s wealth is the total value of all the assets members own less their debts, which are also known as liabilities. Wealth is a measure of the economic resources a family controls at any given time.

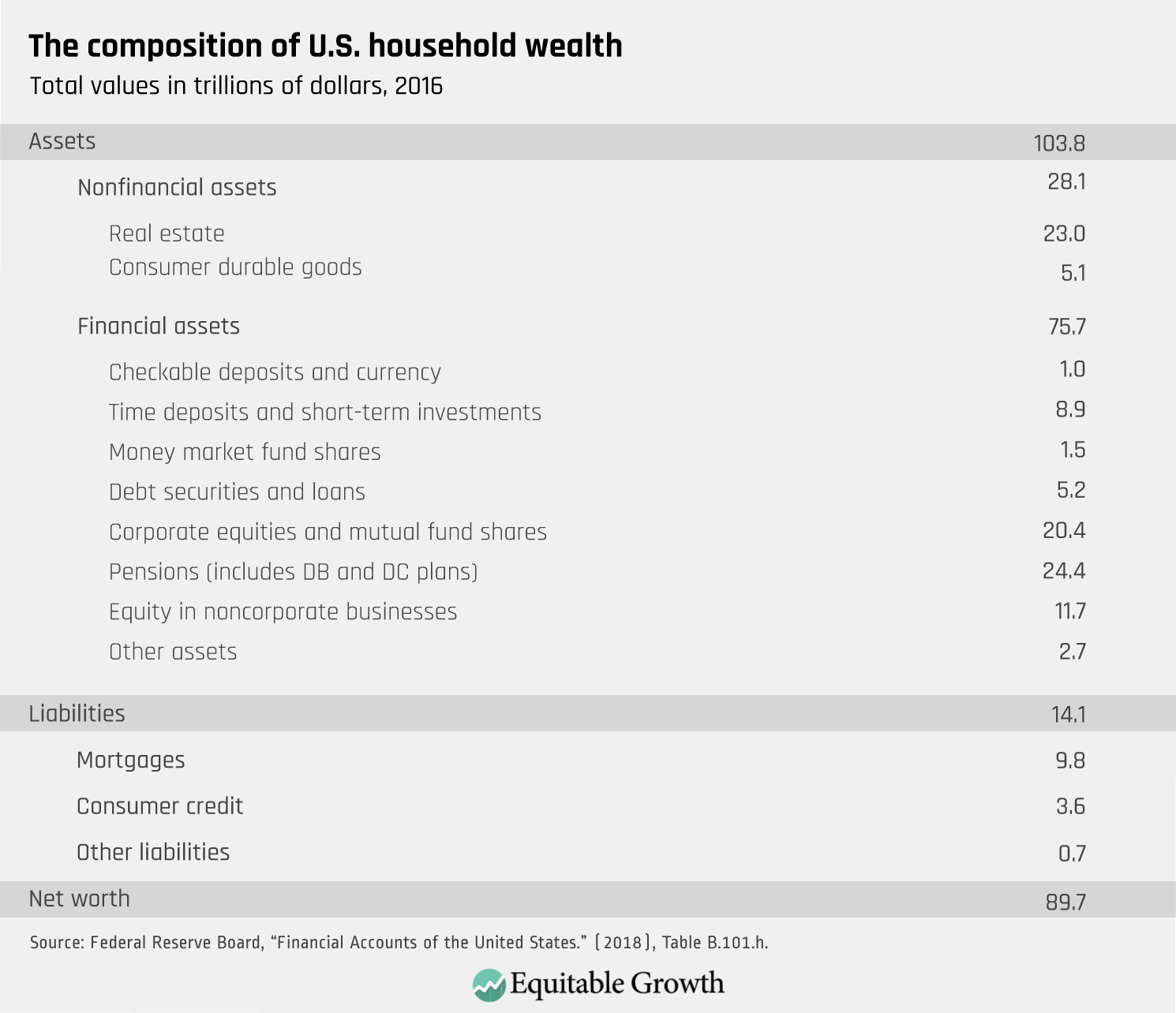

Assets can be financial or nonfinancial. Bank accounts and retirement savings plans such as 401(k) plans are common financial assets. Cars and houses are common nonfinancial assets. Home mortgages are the largest source of debt for U.S. households. High-wealth families own assets that are much less commonly held by the broader population. These less-common assets include ownership stakes in noncorporate businesses, complex financial products such as investments in hedge funds or private equity funds, and valuable works of art. See Table 1 for a breakdown of U.S. household wealth as estimated by the Federal Reserve’s Financial Accounts of the United States in 2016.1

Table 1

What is a net worth tax?

A net worth tax is an annual tax on the wealth a family owns. A key feature of net worth taxes is that the tax is imposed on the people who ultimately own assets, not intermediaries. Notably, this means that a business does not pay tax on its assets; instead, shareholders pay tax on the value of the business, which includes the value of its assets.2 Net worth taxes are sometimes referred to as wealth taxes, but a net worth tax is only one way of taxing wealth. Property taxes, capital gains taxes, and corporate taxes are also taxes on wealth.

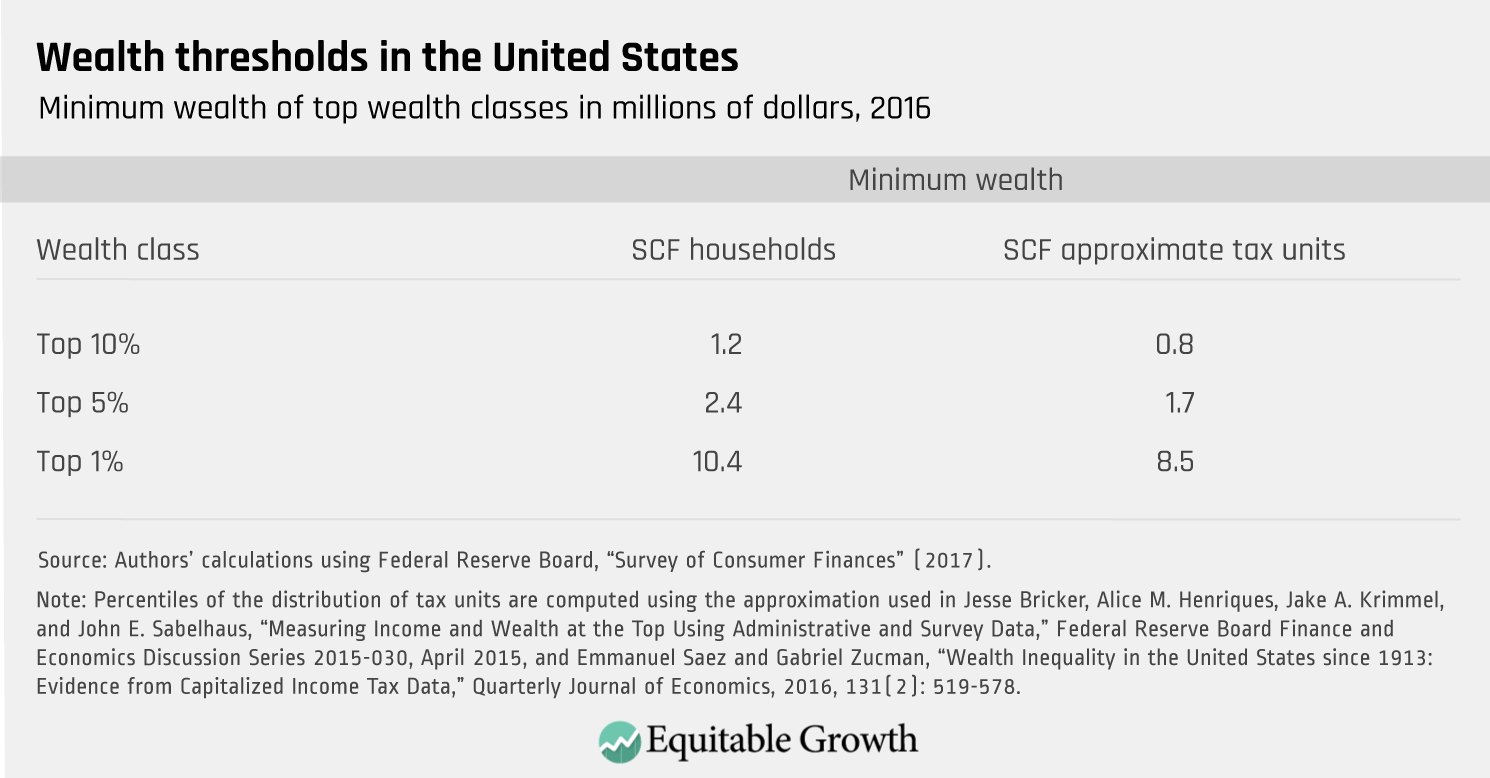

Two key design choices for a net worth tax are whose wealth to tax and what kinds of wealth to tax. Member nations of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development that impose a net worth tax today or did so in the past have typically exempted most families from the tax by providing a generous exemption. Families pay the tax only if their wealth exceeds the exemption. A net worth tax at a 1 percent rate with a $1 million exemption, for example, would charge a family a tax equal to 1 percent of their wealth above $1 million. Such an exemption would have exempted more than 90 percent of U.S. tax units in 2016.3 (See Table 2.) A family with $2 million of wealth would owe $10,000 in tax, for an effective rate of 0.5 percent on their total wealth. Just as with income taxes, net worth taxes may have a flat rate or a progressive rate structure.

Table 2

Net worth taxes may also offer preferences for assets such as owner-occupied real estate or retirement savings. While these preferences may be motivated by reasonable policy concerns, tax preferences are generally not the best approach to addressing them. As with any other tax, policymakers should aim for a broad base to minimize the burden of the tax for any desired level of revenue. But to avoid unnecessary complexity, net worth taxes typically provide generous preferences or exemptions for consumer durables such as home furnishings.

How is wealth taxed in the United States today?

The United States does not have an explicit net worth tax, but both the federal government and state and local governments tax wealth in a number of ways under current law. Perhaps most notably, state and local governments in the United States rely on property taxes to an unusual extent among OECD countries.4 Property taxes are taxes on the value of a specific asset—real estate. In contrast to net worth taxes, property taxes do not subtract the value of the mortgage from the value of the asset in computing the tax liability. The federal government also taxes capital gains, dividends, corporate income, income attributable to pass-through businesses, and estates—all of which are taxes on wealth.

There are important economic relationships between a net worth tax and income taxes. Assets have value primarily due to the stream of income they are expected to generate or could generate in the case of owner-occupied housing. Net worth taxes and income taxes differ in terms of the timing of tax payments, how they apply to uncertain income streams, and how they apply to complex business structures, among other dimensions.

A major weakness of the federal government’s current approach to taxing wealth is that capital gains are realized only when an asset is sold. Increases in the value of an asset are ignored for tax purposes until the owner sells the asset. Thus, asset owners can choose when to pay tax because they can choose when to sell assets. One reason policymakers may find a net worth tax attractive is that it addresses this limitation of the current system.

One factor that may partially explain why the United States does not have a federal net worth tax is that there is debate as to the constitutionality of a federal net worth tax. But the unresolved nature of this debate is no reason to foreclose discussion of the merits of the tax, and there are compelling reasons such a tax should be upheld.5

Who would bear the burden of a net worth tax?

A net worth tax applied to wealthy families in the United States would be highly progressive. The economic incidence of the tax—meaning the economic burden of the tax, which is conceptually distinct from the legal obligation to pay the tax—would lie primarily on the owners of wealth.6 Taxing wealth ownership (as a net worth tax does) rather than asset use (as business taxes indirectly do) allows for superior targeting of the burden of the tax on wealth owners.

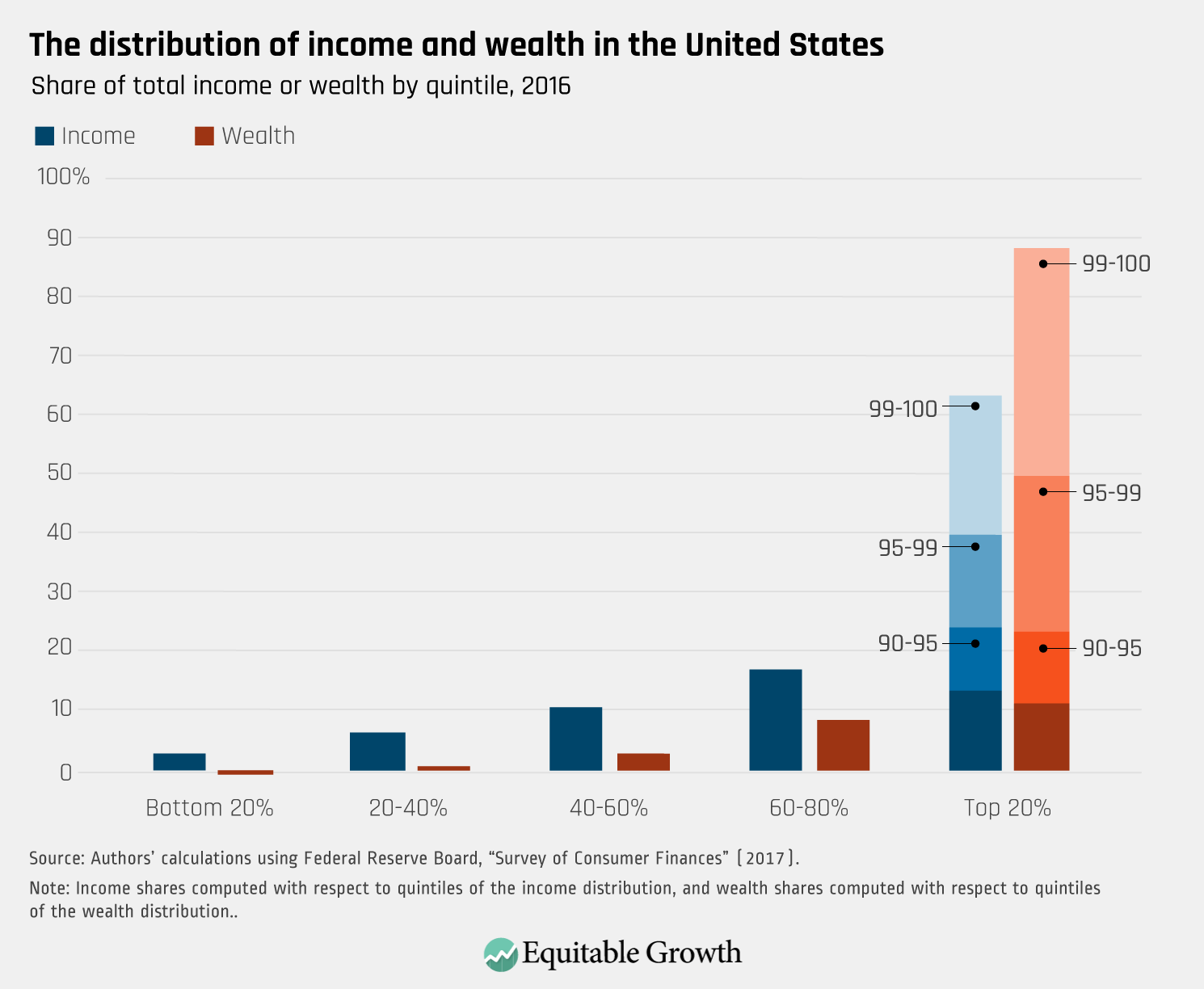

The distribution of wealth itself in the United States is highly skewed. The wealthiest 1 percent of families holds about 40 percent of all wealth, and the wealthiest 5 percent holds 65 percent of all wealth.7 (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

Families with high wealth relative to their income will bear relatively more of the burden of a net worth tax than an income tax. Families with low wealth relative to their income will bear relatively less. A net worth tax, or other means of taxing wealth, would thus generally shift the tax burden not only from low-wealth families to high-wealth families, but also from younger families to older families and from families of color to white families.

How much revenue could a net worth tax raise?

The revenue potential of a net worth tax in the United States is large. The wealthiest 1 percent of families holds $33 trillion in wealth, and the wealthiest 5 percent holds $57 trillion in wealth.8

Estimates of the revenue raised by a net worth tax are highly uncertain, as they depend on both the detailed specification of the tax and assumptions about how families would respond to the tax, for which little guidance is available in the academic literature. One important ingredient in this estimation is the elasticity of taxable wealth, which summarizes the various behavioral responses to the tax. Those responses affect the amount of wealth that taxpayers would report on their tax returns. To reduce their net worth tax liabilities, high-wealth individuals might, for example, hide wealth abroad or increase their spending (thus reducing their wealth).

Probably the most significant challenge in implementing a net worth tax is that determining tax liabilities requires a valuation for all of the assets subject to the tax. In many cases, it is straightforward to generate these valuations. Publicly traded securities, for example, have readily available market valuations. Local governments regularly value real estate for property taxes, though not without dispute and subject to rules that artificially alter the value in some jurisdictions. But other assets are harder to value such as ownership stakes in a closely held business. Owners of a closely held business would have a financial incentive to undervalue them to avoid paying tax. This type of response would be reflected in an estimate of the elasticity of taxable wealth and thus also in a revenue estimate.

Why might policymakers adopt a net worth tax?

Taxes impose burden to raise revenues. In developing tax legislation, policymakers should evaluate the change in burden and the change in revenues that would result.9 Policymakers looking for a highly progressive tax instrument that raises substantial revenue would find a net worth tax appealing. Such a tax would impose burden primarily on the wealthiest families—reducing wealth inequality—and could raise substantial revenues.

As noted above, the United States taxes wealth in several forms already. Thus, the policy debate is less about whether to tax wealth and more about the best ways to tax wealth and how much it should be taxed. A net worth tax could be a useful complement to—or substitute for—other means of taxing wealth, as well as a tool for increasing overall taxation of wealth.

End Notes

1. Federal Reserve Board, “Financial Accounts of the United States” (2018), Table B.101.h, available at https://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/z1/. While more recent estimates are available in the Financial Accounts, estimates are presented for 2016 for consistency with the estimates based on the Survey of Consumer Finances for which 2016 is the most recent data available.

2. Some countries that impose a net worth tax on individuals also impose a similar tax on businesses, but such a tax is conceptually distinct from a net worth tax, and the properties of such a tax differ from those of a net worth tax.

3. Authors’ calculations using the Federal Reserve Board’s Survey of Consumer Finances. Percentiles of the distribution of tax units are computed using the approximation used in Jesse Bricker and others, “Measuring Income and Wealth at the Top Using Administrative and Survey Data,” Federal Reserve Board Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2015-030 (Washington: Federal Reserve Board, 2015), and Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman, “Wealth Inequality in the United States since 1913: Evidence from Capitalized Income Tax Data,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 131 (2) (2016): 519–578.

4. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, “Revenue Statistics – OECD Countries: Comparative Tables” (2018), available at https://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?DataSetCode=REV.

5. See, for example, Bruce Ackerman, “Taxation and the Constitution,” Columbia Law Review 99 (1) (1999): 1–58; Dawn Johnsen and Walter Dellinger, “The Constitutionality of a National Wealth Tax,” Indiana Law Journal 93 (1) (2018): 111–137.

6. See, for example, David Seim, “Behavioral Responses to Wealth Taxes: Evidence from Sweden,” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 9 (4) (2017): 395–421; Marius Brülhart and others, “The Elasticity of Taxable Wealth: Evidence from Switzerland,” Working Paper (2017). Though neither analysis is explicitly an analysis of incidence, the findings are suggestive that the incidence of net worth taxes would lie primarily on wealth owners.

7. Authors’ calculations using the Federal Reserve Board’s Survey of Consumer Finances. The distribution of income and wealth is computed relative to SCF households rather than tax units, as the tax unit approximation relied on above is only reasonable for top income and wealth classes.

8. Authors’ calculations using the Federal Reserve Board’s Survey of Consumer Finances. The distribution of wealth is computed relative to SCF households rather than tax units, as the tax unit approximation relied on above is only reasonable for top income and wealth classes. The wealth held by the stated share of tax units would be expected to exceed these estimates. Aggregate wealth relies on the Survey of Consumer Finance’s definition of wealth.

9. Greg Leiserson, “Assessing the Economic Effects of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2018); Greg Leiserson, “If U.S. Tax Reform Delivers Equitable Growth, A Distribution Table Will Show It” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2017).