The flat Phillips Curve and U.S. labor’s share of income

How flat is the Phillips Curve—the relationship between unemployment and inflation? This question is very much on the minds of U.S. central bankers because over the past several years the unemployment rate has dropped, yet inflation has remained subdued. That dynamic has many economists and analysts arguing that the Phillips Curve looks flat, meaning lower unemployment won’t lead to much higher inflation.

Now, it seems, monetary policymakers at the Federal Reserve agree, argues Tim Duy of the University of Oregon. After last week’s meeting of the Federal Open Markets Committee, where monetary policymakers released their projections of unemployment, inflation, and interest rates, Duy contends that they are now among those who believe in a flat Phillips Curve and are betting on it in future plans for monetary policy. If he’s correct, then what might the central bankers be observing that might explain the lack of an inflationary response to a tighter labor market?

The Phillips Curve can break down in a number of ways because the process of transforming lower unemployment to higher inflation has several steps. In the past, faster wage growth passed through into higher inflation, as firms needed to increase prices to make up for higher wages. But a look at the data shows that inflation appears less responsive to wage growth than in the past. Higher wages should push up costs and therefore prices, yet the breakdown of this relationship might be due to some more cushion in companies’ balance sheets—namely, profits.

The share of income going to labor in the United States has been on the decline since about 2000. A declining labor share of income might give companies more space to deal with higher wages. If the decline is due to increasing bargaining power of employers, for example, then a higher share of income going to labor wouldn’t necessarily mean higher inflation because employers can afford to absorb those slightly higher costs without biting too much into their profits.

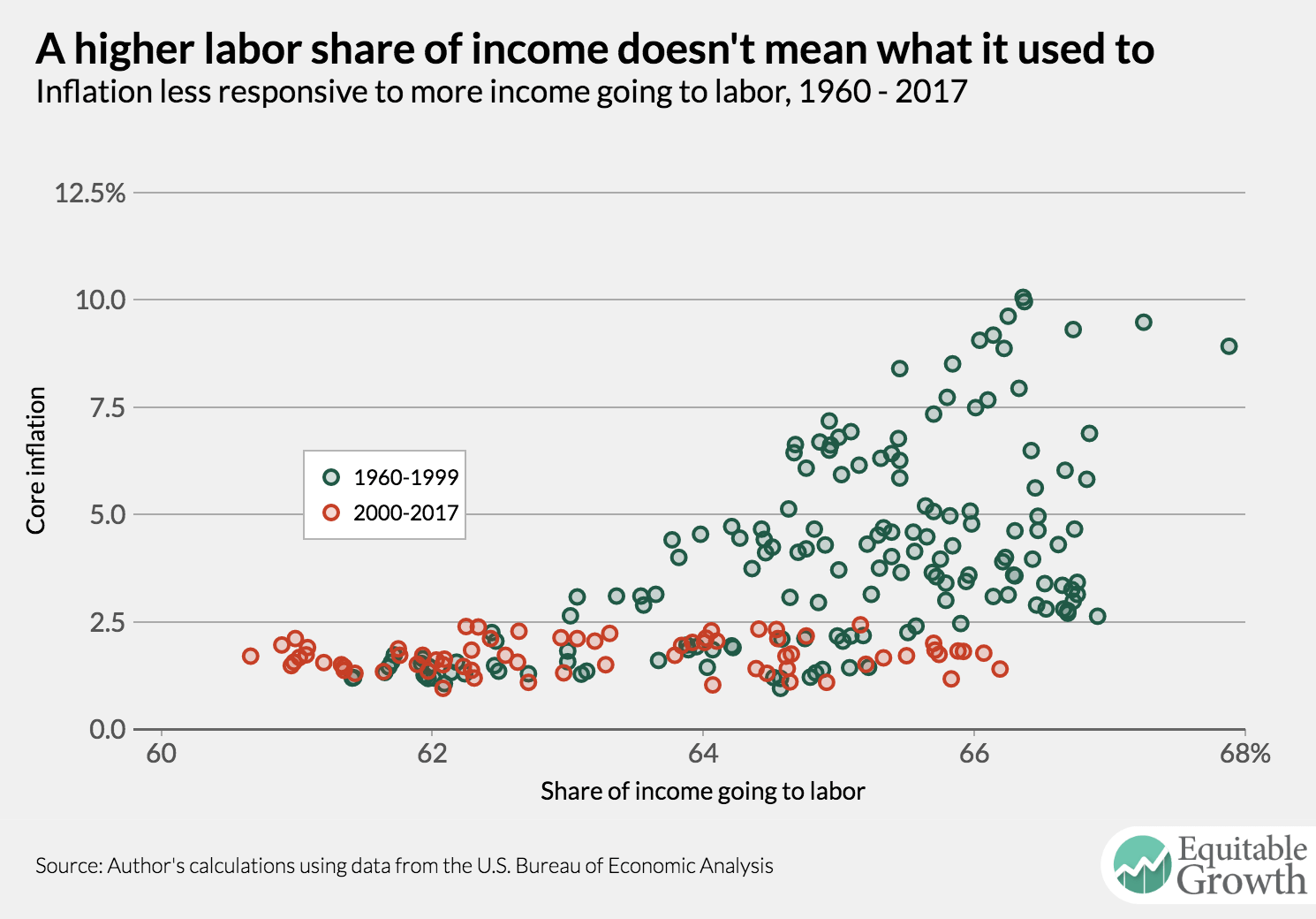

But if the decline in the U.S. labor share of income is due to changes in productivity growth, then letting the labor share increase could set off inflationary pressures. Firms would not have as much cushion to raise wages out of profits and would need to raise prices. It’s not clear which story holds up better without turning to the data, but a quick look suggests the first scenario might hold more truth. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

The chart above shows that since 2000, when the U.S. labor share started its decline, inflation seems unrelated to the amount of income going to labor. Look at the flat relationship between inflation and the labor share during this time period—the red dots. A simple regression analysis shows no statistically significant relationship. A higher labor share of income was associated with higher inflation during earlier time periods—the green dots—but the relationship weakened over time. By the 2000s, the relationship disappeared.

In short, the Federal Reserve might have nothing to fear from a rising labor share of income. A potential new member of the central bank has said as much in the past. In a 2014 analysis for the asset management firm PIMCO, Richard Clarida (the rumored frontrunner to be the next Federal Reserve vice chair) pointed out the lack of pass-through from a higher labor share to higher inflation.

The possible reasons behind the currently flat Phillips Curve are numerous, and whether this relationship will hold up for long is very much up for debate. But the fact that a higher labor share isn’t a clear cut sign that accelerating inflation will soon arrive might give the Fed some comfort that its recent bet on a flatter Phillips Curve might pay off.