The starting point

Almost all observers of the U.S. corporate tax system agree that the system is broken and in desperate need of reform. The United States has one of the highest statutory corporate tax rates among peer nations, yet we raise comparatively little corporate tax revenue as a share of our gross domestic product, or GDP. Our tax base is notoriously narrow. There are special tax breaks—including accelerated depreciation, special deductions for production income, and many smaller loopholes—alongside an incoherent system for taxing business income, resulting in disparate tax treatment based on the organizational form of business.

Download FileProfit shifting and U.S. corporate tax policy reform

In the international sphere, the problems are worse. Several features of the U.S. tax system directly encourage profit shifting, resulting in substantial erosion of the U.S. corporate tax base as income is shifted from the United States to tax havens such as Switzerland, Bermuda, or the Cayman Islands. Some of these features are systemic (for example, the ability of multinational firms to defer taxation on foreign income until it is repatriated) and some of them are ad hoc (such as “check-the-box” rules that allow the creation of “stateless” income1). Overall, these features enable corporate tax base erosion. My estimates suggest that such profit shifting probably costs the U.S. government more than $100 billion in revenue per year.

International corporate tax systems in the United States and elsewhereThe United States uses a worldwide system of taxation that taxes the foreign income of U.S. resident firms. Still, for most foreign income, U.S. taxation only occurs when the income is returned to the United States, or repatriated.2 Corporations also receive tax credits for foreign income taxes paid that they can use to offset U.S. tax liabilities, including tax due on royalty income from abroad. In contrast, under a territorial system of taxation, foreign income is normally exempt from taxation. Under a territorial system, there is a stronger incentive to shift income out of the domestic tax base than under current U.S. law, since income booked abroad is permanently exempt from domestic taxation instead of being tax-deferred until repatriation. For this reason, some territorial countries have also adopted tough base-erosion protections whereby categories of foreign income are taxed currently, even without repatriation. Current taxation may be triggered, for example, if the foreign tax rate is less than some threshold rate. |

Revenue concerns are not the only motivator for business tax reform in the United States, however. The multinational corporate community is also displeased by the status quo and is pushing reforms that would further U.S. business “competitiveness.” Multinational business interests fault the U.S. tax system for two flaws in particular: the relatively high corporate statutory rate, and the fact that U.S. rules purport to tax the “worldwide” income of U.S. multinational firms. Yet both of these features have more bark than bite. U.S. multinational firms have used careful tax planning to generate effective tax rates that are far lower than the statutory rate, and often in the single digits.3 Further, the U.S. tax system places a very low (and in some cases negative) tax burden on foreign income.4

Given the reality on the ground, one would expect that U.S. multinational firms would be relatively content with the present system. Yet there is a crucial problem: The U.S. tax system generates a very light burden on foreign income, but if multinational firms repatriate that income in order to issue dividends or repurchase shares, they need to pay U.S. tax.5 This repatriation “lock-out” problem has become increasingly problematic due to three factors:

- Multinational firms are victims of their own tax-planning success. Profit shifting in prior years has resulted in large stockpiles ($2 trillion) of foreign profits that are growing more rapidly than either domestic profits or measures of foreign business activity.

- Foreign countries have been engaging in tax competition, lowering their corporate tax rates in an attempt to attract global business activity. These lower tax rates generate fewer foreign tax credits to offset taxes that would be due upon repatriation.

- As part of the American Jobs Creation Act of 2004, the U.S. government gave U.S. multinational firms a temporary holiday for repatriating income at a low rate of 5.25 percent. This holiday dramatically increased repatriations, but the inflow of funds was largely used for share repurchases and dividend issues, and did not boost employment or investment despite the hopeful title of the legislation.6 More importantly, the holiday gave multinational firms a signal that there was no reason to pay the full tax due at repatriation—instead, one should wait for the next holiday or lobby for a tax system that exempts foreign income entirely.7

Some in the corporate community have even threatened corporate inversions if favorable corporate tax reforms are not forthcoming— including the shareholder activist Carl Icahn, who has invested $150 million in a super PAC aimed at corporate tax policy changes.8

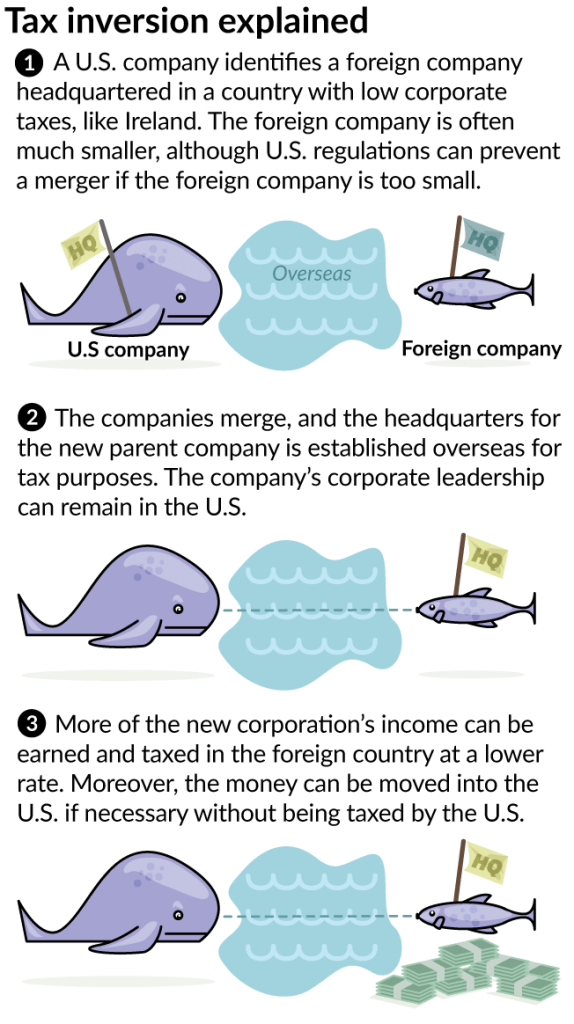

A corporate inversion is a restructuring of a multinational corporation, often combined with a merger or acquisition, that results in the multinational corporate headquarters being shifted abroad to a tax-favored location; the U.S. firm is then an affiliate of a foreign parent. As one observer in The Wall Street Journal put it, “the foreign minnow swallows the domestic whale.”9 Corporate inversions make it easier to access foreign profits without tax due at repatriation, and they also facilitate future profit shifting by reducing the constraint associated with U.S. earnings-stripping rules.10

A corporate inversion is a restructuring of a multinational corporation, often combined with a merger or acquisition, that results in the multinational corporate headquarters being shifted abroad to a tax-favored location; the U.S. firm is then an affiliate of a foreign parent. As one observer in The Wall Street Journal put it, “the foreign minnow swallows the domestic whale.”9 Corporate inversions make it easier to access foreign profits without tax due at repatriation, and they also facilitate future profit shifting by reducing the constraint associated with U.S. earnings-stripping rules.10

This thirst for corporate tax reform is motivated by important failures of our current tax system—in particular, the combination of deferral and profit shifting. Still, it is important to recognize that reformers of the corporate tax system will face an essential dilemma. Reforms that further lighten the tax burden on foreign income that are unaccompanied by serious base-erosion measures may please the multinational corporate community, but such reforms would make a bad corporate tax base erosion problem worse. Exempting foreign income from taxation altogether will turbocharge the already-large incentive to earn income in low-tax countries by removing the remaining constraint on profit shifting (the tax due upon repatriation). Yet serious measures to protect the corporate tax base often do not win the approval of multinational business interests because many such measures would have the net effect of increasing their tax burden on foreign income.

These vexing international tax problems are not occurring in a vacuum. There has been heightened attention to the problems of corporate tax base erosion and profit shifting in many countries, driven in part by increased press attention to the large scale of this problem and the tax avoidance strategies of well-known multinational firms such as Starbucks Corp., Microsoft Corp., Google Inc., and others. There have been prominent hearings in the U.K. parliament on corporate tax avoidance, and recent European Commission rulings have disallowed tax breaks in Belgium, Ireland, and Luxembourg.

In response to these types of concerns, the developed and leading developing country members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the Group of Twenty (G-20) launched a Base Erosion and Profit Shifting initiative to make a concrete action plan of recommendations to help countries address the problems of corporate profit shifting. The initiative identified 15 action items to address their concerns, and after two years of work, the final reports were issued in October 2015, totaling nearly 2,000 pages.

This is a significant effort at international tax cooperation, but it remains to be seen if this process will prove successful at stemming corporate tax base erosion. Many aspects of this process are useful, including the recommendation for country- by-country reporting, but adoption of these guidelines is voluntary, and some of the most contentious areas remain problematic. In the meantime, the scale of the erosion problem afflicting the U.S. corporate income tax base grows swiftly, as I describe in the next section of this paper. Yet several modest reforms and more sweeping solutions to the problem by U.S. policymakers are largely at hand for implementation. These solutions are detailed in the closing sections of this report.

The scale of the profit-shifting problem

There is indisputable evidence that the erosion of the U.S. corporate income tax base is a large and increasing problem. In this section, I will summarize original research that employs the best publicly available data to estimate the cost of profitshifting activity to the U.S. government.11 I also extend these estimates to consider the possible magnitudes of revenue loss for other non-haven governments. These estimates indicate a substantial problem: Revenue loss to the U.S. government likely exceeds $100 billion per year at present, and revenue loss to the group of non-haven countries (including the United States) likely exceeds $300 billion per year at present.12

The analysis makes use of U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis survey data on U.S. multinational firms. Completion of the surveys is required by law, yet the data are not used for tax or financial reporting purposes, and confidentiality is assured. The OECD describes these data as an example of current “best practices” in data collection that allow measurement of base erosion and profit shifting.13

Even a cursory examination of the data indicates the large extent of the profitshifting problem. Among the top 10 profit locations for the overseas affiliates of U.S.-based multinational corporations,14 in 7 out of 10 cases (Netherlands, Ireland, Luxembourg, Bermuda, Switzerland, Singapore, and the Cayman Islands), these countries are havens with effective tax rates of less than 5 percent. Together, these countries are responsible for 50 percent of all foreign profits of U.S. multinational firms. Yet they account for very little of the real economic activity of U.S. multinationals; as a group, they account for only 5 percent of foreign employment. These are also small countries, with a combined population less than that of either Spain or California.

It is also immediately apparent from the data that real economic activities are much less sensitive to tax rate differences across countries. The top 10 foreign countries where U.S. multinationals employ workers, for example, are all large economies with big markets. (See Figure 1.) What’s more, the effective tax rates are not particularly low for this set of countries, as none of these 10 countries has an effective tax rate below 12 percent.

Figure 1

The pressing question of this research is how the booking of profits would differ absent profit-shifting motivations. U.S. multinational firms report $800 billion in gross profits in countries with tax rates that are lower than 15 percent. How much excess profit is booked in these countries? And if it were not booked in low-tax countries, where would it be?

To answer this question, I first estimate the tax sensitivity of U.S. multinational affiliate profits, controlling for other factors that may influence the profitability of affiliates. I find that reported profits are quite tax-sensitive, with a 2.92 percent change in profits for each 1 percentage point change in tax rates, controlling for other factors that influence profits such as the scale of affiliate operations in particular countries, as well as country and time intercept terms.15 There is some important recent work that suggests profits are probably non-linearly related to tax rates, and if that consideration were included in my analysis, results would indicate an even larger degree of profit shifting.16

This measure of tax sensitivity is then used to calculate what profits would be in the countries of operation of U.S. affiliates absent differences in tax rates between foreign countries and the United States. A fraction (38.7 percent in 2012) of the hypothetically lower foreign profits are then attributed to the U.S. tax base.17 The United States has a statutory tax rate of 35 percent, but in this analysis, I assume that the U.S. effective tax rate would be lower (30 percent) to allow for some degree of base narrowing in practice, and that this lower tax rate would apply to any increased income in the U.S. tax base.18 Finally, this number is scaled up, under the assumption that foreign multinational firms also engage in income shifting outside of the United States.19

Table 1 and Figure 2 show the major locations where income is shifted. In cases of high-tax-rate countries with effective tax rates above my assumed U.S. rate—for example, in 2012, Denmark, Argentina, Chile, Peru, India, Italy, Japan, and others—foreign profits would be higher, but in many other cases, foreign profits would be lower. In 2012, I estimate that profits in the lowest-tax countries (with effective tax rates of less than 15 percent) were too high (due to tax incentives) by $595 billion, and these countries account for 98 percent of the total quantity of profit shifting away from the U.S. tax base.

Table 1

Figure 2

Indeed, the estimates of excess income booked just within the seven important tax havens highlighted in Table 1 account for 82 percent of the total. Of the income booked in Bermuda ($80 billion), the Caymans ($41 billion), Luxembourg ($96 billion), the Netherlands ($172 billion), and Switzerland ($58 billion), this method suggests that profits absent income-shifting incentives would instead be $10 billion in Bermuda, $9 billion in the Caymans, $15 billion in Luxembourg, $33 billion in the Netherlands, and $15 billion in Switzerland. In comparison, profits booked in France and Germany in 2012 were $13 billion and $17 billion, respectively.

These estimates—including the main estimate based on the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis income series (net income plus foreign taxes paid), as well as an alternative (lower) estimate using the agency’s direct investment earnings series,20 are summarized in Table 2 below. The table shows the total income earned abroad by foreign affiliates of U.S. firms; the estimated U.S. tax base increase if income-shifting incentives were eliminated; and the reduction in U.S. corporate income tax revenues due to income shifting, assuming that marginal revenues are taxed at 30 percent.21 Actual corporate tax revenues in the corresponding year are presented as a comparison. By 2012, the revenue cost of income-shifting behavior is estimated at $111 billion.

Table 2

There is a substantial lag associated with the release of the Bureau of Economic Analysis survey data, so the latest analysis is already a few years old. But if one scales up the estimates to this year at a 5 percent growth rate then the total revenue lost to profit shifting in 2012 (between $77 billion and $111 billion) would be approximately $94 to $135 billion by 2016.22

Figure 3 illustrates the change in these estimates of revenue loss due to profit shifting over the period from 1983 to 2012. This strong upward trend is not a reflection of increasing tax responsiveness over this time period, since that is assumed to be constant in the analysis. Instead, it is due to two factors. First, and most importantly, the total amount of foreign profits is increasing dramatically over this period. Income of all foreign affiliates was $525 billion in 2004, growing to $1.2 trillion by 2012. Direct investment earnings increased by similar magnitudes, more than doubling in eight years. Second, the average foreign effective tax rate continued to fall over this time period, also contributing to income-shifting incentives.

Figure 3

Of course, there are several assumptions required for this analysis that generate uncertainty surrounding these estimates. In the full research paper, I enumerate the sources of uncertainty and discuss their possible effects on the estimates.23 I have sought to err on the side of making conservative assumptions. Still, many assumptions have no direction of bias, and when an assumption could lead to an overestimate, I provide alternative estimates.

These corporate profit-shifting problems are not unique to the United States. In the full research study, I also provide a speculative extension of the analysis to other nonhaven countries, based on data from the Forbes Global 2000 list of important global corporations.24 I estimate that profit shifting is generating revenue costs to governments of about $340 billion per year at present.25 These estimates cover countries that are headquarters to most Forbes Global 2000 firms, excluding those countries with tax rates of less than 15 percent, and including the United States, which accounts for approximately one-third of the total revenue loss.

Unfortunately, data are insufficient for offering an estimate for less-developed countries using this method. International Monetary Fund economists Ernesto Crivelli, Michael Keen, and Ruud A. de Mooij indicate, however, that the profit-shifting problem is likely to be particularly large and consequential for developing countries.26

These estimates are based on the best publicly available data, careful methodology, and conservative assumptions. Further, they are compatible with the work of other researchers at the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, the International Monetary Fund, the Joint Committee on Taxation, and elsewhere.27

What to do (and what not to do) about profit shifting

This section will consider policy solutions to the profit-shifting problem, recognizing the dilemma posed by today’s political realities as our starting point. Perhaps understandably, the most stalwart (and well-funded) advocates for corporate tax reform are the corporations themselves. They are interested in reforms that would ostensibly make corporate taxpayers more “competitive” by lowering foreign tax burdens. Such reforms are likely to make the corporate tax base erosion problem worse, however, while serious reforms that would address corporate tax base erosion would likely raise the net burden on foreign income earned by multinational firms, reducing corporate support for reform. This leaves policymakers with an essential dilemma.

What not to do

Many in the multinational corporate community use the argument of “competitiveness” to suggest that the United States should align its system with those of other countries by lowering our statutory tax rate and adopting a territorial system of taxation. Yet U.S. multinational firms already face low effective tax rates that are comparable to those of firms headquartered in other countries, and very little tax is presently collected on foreign income.28 Indeed, a well-designed territorial system could easily raise the tax burden on foreign income. So, presumably, those that push for adoption of a territorial system under the guise of competitiveness concerns truly have in mind a “toothless territorial” system that would lower the tax burden on foreign income.

Yet every indicator suggests that U.S. multinational firms don’t have a competitiveness problem, but rather are healthy and thriving. Corporate profits as a share of U.S. gross domestic product during 2012-2014 period were as high as any point since the 1960s.29 The United States is home to a disproportionate share of the Forbes Global 2000 list of the world’s most important corporations.30 And, finally, U.S. multinational firms are world leaders in tax avoidance, and as a result, they often achieve single-digit effective tax rates, making them the envy of the world in terms of tax planning competitiveness.31

Pushing for a toothless territorial system without serious and effective base erosion protection measures would risk worsening the erosion of the already shrinking U.S. corporate income tax base. Exempting foreign income from taxation would relax the remaining constraint on shifting income abroad: the potential tax due upon repatriation. This turbocharges the already large incentive to book income in low-tax havens, likely generating large revenue losses.

Small changes that would help

Rejecting a “toothless” territorial system and the competitiveness arguments that lie behind this proposal does not mean that policymakers do not need to address the “lock-out” effect caused by the combination of deferral and profit-shifting. It is also important to address corporate inversions—the “self-help” version of a toothless territorial system—given the frequent adoption of this corporate tax strategy by U.S. multinationals. There are several small policy changes that would be helpful; more fundamental reforms are addressed the following section.

First, it is conceivable that a “tough” territorial system, like the hybrid systems of many of our trading partners, would allow one to address some of the problems of the current system (including the lock-out effect) without eviscerating the corporate tax base. Such a transition to a hybrid/territorial system would include a transition tax on accumulated foreign profits as well as carefully designed measures to protect the U.S. corporate income tax base. Base-protection measures would currently tax foreign income that did not qualify for exemption, perhaps through a minimum tax approach, as suggested by recent proposals from the Obama administration. Law professors J. Clifton Fleming, Robert J. Peroni, and Stephen E. Shay suggest an updated Subpart F regime, which currently taxes some types of foreign income, alongside disqualifying the exemption for royalty income, and creating a realistic allocation of expenses to foreign-source income.32

Still, Fleming, Peroni, and Shay also warn that many recent proposals to move toward exemption have fundamental weaknesses that would increase the erosion of the U.S. corporate tax base.33 For political economy reasons, one might worry that tough base-protection measures would be challenged or eroded over time. Since the main motivation for adopting a territorial system is coming from multinational business interests that would oppose truly tough features of a territorial regime, the details of any such proposal are crucial.

Second, corporate tax reforms could strengthen our system by lowering the statutory rate in combination with provisions that would close loopholes, thus better aligning the “label” of the tax system that describes the law with the reality on the ground that determines the tax treatment of firms. A prime example of a loophole that could be closed is the “check-the-box” rule that facilitates income shifting. Recent Obama administration proposals include a more comprehensive list of possible loopholes that could be closed,34 and an even longer list of guidelines and recommendations to address profit shifting is included in the reports on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and the Group of Twenty.35

Third, measures could also be taken to stem corporate inversions, regardless of the direction of larger corporate tax reforms. Recent U.S. Treasury regulations, for example, have made inversions more difficult. More could be done, though, including increasing the legal standard for a foreign affiliate to become a parent and a so-called management-and-control test to determine the location of corporate residence.36 Another area that could be revised in response to inversions is the earnings-stripping rules under Section 163(j) of the Internal Revenue Code.37 Such a change would also help address the profit-shifting problem more generally, including in cases in which multinational firms have not inverted. Finally, an exit tax would be a key anti-inversion policy tool. An exit tax would be levied on repatriating companies based on the U.S. tax due on outstanding stocks of income that have not been repatriated.38

More fundamental solutions

The smaller steps just discussed do not fundamentally change the most vexing issue associated with international taxation: the difficulty of determining the source of income (and expenses) in a modern global economy.

Our present system of international taxation relies on the fiction that global firms can neatly account for their income and expenses in each jurisdiction in which they operate. Yet the entire point of a multinational firm is to achieve greater profits than the component firms would achieve operating at arm’s length, by exploiting firm specific advantages to their most profitable end by undertaking transactions across borders yet within the firm. Assigning this additional profit associated with global integration to a particular source is a fraught exercise, made even more vexing in a modern economy where the source of much value is intangible.

This potent brew of globally integrated businesses, intangible sources of economic value, and a creative and industrious tax-planning industry make our system of international taxation costly to administer, difficult to comply with, and mind-numbingly complex. These factors also help explain the large magnitudes of profit shifting and corporate tax base erosion demonstrated in the prior section. More fundamental reforms could better align the tax system with the modern global economy.

Option 1: Worldwide consolidation

Under worldwide consolidation, a U.S.-headquartered multinational firm would simply consolidate its entire global operations (across the parent and all foreign affiliates) for tax purposes, including losses.39 Income would then be taxed currently, allowing a credit for foreign taxes. This proposal is discussed in more detail by the Joint Committee on Taxation, and favored by U.S. corporate tax experts Edward D. Kleinbard at the University of Southern California and Reuven S. Avi-Yonah at the University of Michigan.40

A worldwide consolidation approach has several benefits relative to the current system. Foremost, there would be less tax-motivated shifting of economic activity to book income to low-tax locations, since such shifting would be less likely to affect a multinational firm’s overall tax burden.41 There would thus be few concerns about inefficient capital allocation or corporate tax base erosion. Also, there would be no “trapped cash” problem since income would be taxed currently.

Depending in part on the corporate tax rate that would accompany this change, however, the proposal may still raise competitiveness concerns for those U.S. multinational firms with rising foreign tax burdens under consolidation. Of course, if the U.S. corporate tax rate were lowered substantially alongside this change, as proponents typically suggest, this would reduce the concerns about decreased competitiveness.

Some also worry that this proposal would put stress on the definition of residence. Although some have argued that residence is increasingly elective,42 others contend that relatively simple legislation would make it difficult to change residence for tax purposes. Governments could require that corporate residence indicate the true location of the “mind and management” of the firm; both Kleinbard and Avi-Yonah deem a similar U.K. definition of residence to be effective.43 It is also feasible to develop anti-inversion measures along the lines of those suggested above.

Finally, while there is little real-world experience with such a system, it still falls within international norms, since double taxation is prevented through foreign tax credits. The proposal could be implemented without disadvantaging major trading partners, and it could be adopted unilaterally, though Avi-Yonah recommends that countries take a multilateral approach.44

This proposal has some advantages over simply ending deferral. While eliminating deferral (presumably alongside a corporate tax rate reduction) would entail some of the same tradeoffs illustrated here (removal of distortion to repatriation decisions, reduced income shifting, more efficient capital allocation, potential competitiveness concerns, and a greater stress on the definition of residence), it would not truly consolidate the affiliated parts of a multinational firm. Under worldwide consolidation, for example, if losses are earned in foreign countries, they can be used to offset domestic income.

Option 2: Formulary apportionment

Under formulary apportionment, worldwide income would be assigned to individual countries based on a formula that reflects their real economic activities. Often, a three-factor formula is suggested (based on sales, assets, and payroll), but others have suggested a single-factor formula based on the destination of sales.45

The essential advantage of the formulary approach is that it provides a concrete way for determining the source of international income that is not sensitive to arbitrary features of corporate behavior such as a firm’s declared state of residence, its organizational structure, or its transfer-pricing decisions. If a multinational firm changes these variables, it would not affect the firm’s tax burden under formulary apportionment.46

Importantly, the factors in the formula are real economic activities, not financial determinations. A vast body of research on taxation suggests a hierarchy of behavioral response: Real economic decisions concerning employment or investment are far less responsive to taxation than are financial or accounting decisions.47 For multinational firms, this same pattern is clearly shown in the data. There is no doubt that disproportionate amounts of income (compared to assets, sales, or employment) are booked in low-tax countries.

In this way, a formulary approach addresses aspects of both the competitiveness and tax base erosion concerns. Firms would have no incentive to shift paper profits or to change their tax residence since their tax liabilities would be based on their real activities. Concerns about efficient capital allocation, however, may remain. Under a three-factor formula, there is still an incentive to locate real economic activity in lowtax countries. This is somewhat less of a concern under a sales-based formula, since firms will still have an incentive to sell to customers in high-tax countries regardless.48 Also, prior experience in the United States, which uses formulary apportionment to determine the corporate tax base of U.S. states, has indicated that formula factors (payroll, assets, and sales) are not particularly tax-sensitive.49

If all countries were to adopt formulary apportionment, then there would be few concerns about competitiveness. Multinational firms would be taxed based on their real economic activities (in terms of production and sales) in each country, so firms would be on an even footing with other firms (based in different countries) that had similar local operations. If only some countries adopt formulary apportionment then there are ambiguous competitive effects, depending on the circumstances of particular firms.50 Ideally, formulary apportionment would be adopted on a multilateral basis. But if only some countries adopt this approach then there are mechanisms that would encourage other countries to follow early adopters.51 In other research, I provide more detail on the advantages and disadvantages of formulary approaches.52

Concluding observations on the corporate tax in a global economy

This paper argues that the erosion of the U.S. corporate income tax base is a large policy problem. Profit shifting is reducing U.S. government tax revenues by an amount that likely exceeds $100 billion each year, and other countries are facing similar concerns. Yet given the starting point of the current U.S. corporate tax system, potential reformers face a dilemma. Reforms that would protect the tax base may not find support in the multinational business community, which is often more concerned with perceived competitiveness issues associated with the U.S. system. This report shows that such competitiveness problems are more perception than reality, but there are still important distortions created by the combination of deferral and profit shifting that need to be fixed.

I offer several modest reforms that would make improvements, as well as two more fundamental options. But regardless of the path that reformers take, it is important to remember that the corporate income tax has a vital role to play in the U.S. tax system beyond these important revenue concerns. Perhaps most important, it is one of our only tools for taxing capital income, since the vast majority of passive income is held in tax-exempt form, going untaxed at the individual level.53 Capital income has become a much larger share of U.S. GDP in recent decades,54 and capital income is far more concentrated among those with higher incomes than labor income, making the corporate income tax an important part of the progressivity of the tax system.55 The corporate income tax also plays a vital role in back-stopping the personal income tax system, since otherwise the corporate form could become a tax shelter.56

Finally, recent economic theory buttresses the case for taxing capital on efficiency grounds.57 Thus, the case for a healthy corporate tax is alive and well. The remaining question is whether the requisite political will can be summoned to stem corporate tax base erosion in a global economy.

End Notes

1. Stateless income does not fall under any taxing jurisdiction; see Edward D. Kleinbard, “Stateless Income,” Florida Tax Review 11 (2011): 699–773.

2. This is the case for most types of income, but some income, including “passive” income, is taxed currently under subpart F, the U.S.-controlled foreign corporation rules.

3. While domestic firms have far fewer options for lowering their effective tax rate, many multinational firms have achieved single digit tax rates, including Pfizer, prior to their planned inversion. (See Frank Clemente, “Pfizer’s Tax Doging RX: Stash Profits Offshore,” (Washington, DC: Americans for Tax Fairness, 2014), http://www.americansfortaxfairness.org/pfizers-taxdodging-rx-stash-profits-offshore/ and sources within.) Many other companies have achieved comparably low rates. (See, e.g., Christopher Helman, “What the Top U.S. Companies Pay in Taxes,” Forbes.com, April 1, 2010, http://www.forbes.com/2010/04/01/ge-exxonwalmart-business-washington-corporate-taxes.html

4. As noted in the text, the United States exempts much foreign income from tax, since foreign income that is reinvested abroad can escape home taxation indefinitely. Cross-crediting can also reduce the domestic taxation of foreign income, and tax credits from dividends can offset tax that would otherwise be due on other sources of foreign income, such as royalty income. Thus, it is quite possible that a move to a territorial system could raise rather than lower the share of foreign income that is taxed. See: Rosanne Altshuler and Harry Grubert, “Fixing the System: An Analysis of Alternative Proposals for the Reform of International Tax,” Rutgers University Department of Economics Working Paper, 2013. Jane G. Gravelle, “Moving to a Territorial Income Tax: Options and Challenges,” (Washington DC: Congressional Research Service, 2012)

5. In particular, they need to pay U.S. tax, but they can use foreign tax credits to offset U.S. tax due, so income is not taxed twice. However, due to the large amount of income booked in tax havens, many multinational firms have insufficient tax credits to offset the U.S. tax liabilities on desired repatriations.

6. For a review of the evidence, see Jane G. Gravelle and Donald J. Marples, “Tax Cuts On Repatriation Earnings as Economic Stimulus: An Economic Analysis,” (Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service, 2011).

7. These funds are often held in U.S. financial institutions, and are thus available to U.S. capital markets, but U.S. multinational corporations are constrained in their use of these funds. These funds are assets of the firm that increase the firm’s credit worthiness. However, firms cannot return the cash to shareholders as dividends or share repurchases without incurring U.S. corporate tax liabilities upon repatriation.

8. Regarding the super PAC, see: Rebecca Ballhaus, “Carl Icahn to Invest $150 Million in Super PAC,” Wall Street Journal, October 21, 2015, http://www.wsj.com/articles/carl-icahn-to-invest-150-million-in-superpac-1445441825. For Mr. Icahn’s op-ed on the topic, see Carl C. Icahn, “How to Stop Turning U.S. Corporations Into Tax Exiles,” The New York Times, December 14, 2015, http://www.nytimes.com/2015/12/14/opinion/how-tostop-turning-us-corporations-into-tax-exiles.html.

9. See Edward D. Kleinbard, “Tax Inversions Must Be Stopped Now,” Wall Street Journal, July 21, 2014, http://www.wsj.com/articles/edward-d-kleinbard-taxinversions-must-be-stopped-now-1405984126. For a discussion of these points at much greater length, see also Edward D. Kleinbard, “Competitiveness Has Nothing to Do With It.” Tax Notes 144, no, 1055 (2014), http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2476453##.

10. See Kimberly A. Clausing, “Corporate Inversions,” (Washington DC: Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center, 2014), http://www.urban.org/research/publication/corporateinversions/view/full_report.

11. Original research from Kimberly A. Clausing, “The Effect of Profit Shifting on the Corporate Tax Base in the United States and Beyond,” National Tax Journal (forthcoming, December 2016 ), http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2685442.

12. These calculations are based on extrapolating 2012 estimates to 2016, assuming a 5 percent growth rate in foreign profits. For the source of the 2012 estimates, see Clausing, “The Effect of Profit Shifting on the Corporate Tax Base in the United States and Beyond.”

13. OECD, “Measuring and Monitoring BEPS: Action 11 Final Report,” OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project, (Paris: OECD Publishing, 2015), https://www.oecd.org/ctp/measuring-and-monitoring-beps-action-11-2015-final-report-9789264241343-en.htm.

14.

These data are from the BEA’s net income series, adding back foreign income taxes paid to calculate gross income. An alternative series on foreign direct investment earnings is also available; this series avoids some of the double-counting problems that could affect the gross income series, but it also misses some sources of profit shifting. However, the pattern of these data are nearly identical to Figure 1. In that series, the

same seven haven countries are in the top-ten earnings countries, and together they account for 52% of all

foreign direct investment earnings.

15. In “The Effect of Profit Shifting on the Corporate Tax Base in the United States and Beyond,” I provide eight alternative specifications that suggest large, negative, and statistically significant relationships between profits and effective tax rates. The semi-elasticities range from -1.85 to -4.61, with an average estimate of -2.92. These estimates control for many other factors that could affect profitability across countries. Estimated elasticities are quite similar if one instead uses data on the BEA direct investment earnings series. This average is in line with much of the prior literature on tax base elasticities, and it is similar to those found in the meta analyses of the following: Ruud A. De Mooij and Sjef Ederveen, “Taxation and Foreign Direct Investment: A Synthesis of Empirical Research,” International Tax and Public Finance 10 (November 2013): 673–93. Ruud A. De Mooij, “Will Corporate Income Taxation Survive?” De Economist 153, no. 3 (September 2005): 277–301.

16. See Tim Dowd, Paul Landefeld, and Anne Moore, “Profit Shifting of U.S. Multinationals,” U.S. Congress Joint Committee on Taxation Working Paper, (Washington, DC: U.S. Congress Joint Committee On Taxation, 2014). Most profit-shifting is occurring with very low-tax rate countries, so allowing a higher tax elasticity for such countries would increase estimates of the size of profit shifting.

17. The assigned fraction is based on the share of intrafirm transactions that occur between affiliates abroad and the parent firm in the United States, relative to all intrafirm transactions undertaken by affiliates abroad (with both the parent and affiliates in other foreign countries). Thus, in 2012, foreign affiliates of U.S. parent multinational firms undertook 38.7% of their affiliated transactions with the United States; the remaining 61.3% were with other affiliated firms abroad. Of course, this fraction is just a plausible benchmark.

18. This 30% tax rate is also used to calculate the difference between the foreign tax rate and the U.S. tax rate. Using a 35% rate instead would raise the estimates of revenue loss due to profit shifting.

19. While the data do not allow a separate estimate of their profit shifting behavior, I assume that it would increase the revenue costs of income shifting by a factor that is based on the ratio of the sales of affiliates of foreignbased multinational firms in the United States (a proxy for the ability of foreign multinational firms to shift income away from the United States) to the sales of affiliates of U.S. based multinational firms abroad (a proxy for the ability of U.S. multinational firms to shift income away from the United States).

20. The alternative estimate uses the BEA direct investment earnings series. This series avoids double-counting, but also eliminates some types of income shifting. Column 2 indicates total direct investment earnings abroad over the period 2004-2012; data from the BEA are adjusted to include foreign taxes paid and to reverse the BEA’s adjustment of the data by the US parent equity ownership percentage. Column 3 shows the estimated increase in the U.S. tax base, again employing the methodology used for the main estimates. Using this series, the resulting revenue reduction estimates are lower, due to the combined effects of the elimination of double-counting and the omission of some types of income. Unfortunately, with available data, one can not separate these two effects.

21.

Revenue estimates would of course be higher if one assumed that marginal additional profits would be taxed

at the statutory rate.

22. Of course, this growth rate is also arbitrary, but most indicators show a robust growth in reported foreign profits in recent years.

23. Clausing, “The Effect of Profit Shifting on the Corporate Tax Base in the United States and Beyond.”

24. Ibid.

25. The estimate for 2012 is $279 billion. Assuming a 5% growth rate, that would entail a loss by 2016 of $340 billion.

26. Ernesto Crivelli, Michael Keen, and Ruud A. de Mooij, “Base Erosion, Profit Shifting, and Developing Countries,” Oxford University Centre for Business Taxation Working Paper 15/09, (Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund, 2015), http://www.sbs.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/Business_Taxation/Docs/Publications/ Working_Papers/Series_15/WP1509.pdf.

27. See OECD, “Measuring and Monitoring BEPS: Action 11 Final Report”; Crivelli, Keen, and de Mooij, “Base Erosion, Profit-Shifting, and Developing Countries”; Mark P. Keightley and Jeffrey M. Stupak. 2015. “Corporate Tax Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS): An Examination of the Data,” (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, 2015); Dowd, Landefeld, and Moore, “Profit Shifting of U.S. Multinationals.” Gabriel Zucman, “Taxing Across Borders: Tracking Personal Wealth and Corporate Profits,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 28, no. 4 (2014): 121–48; Gabriel Zucman, The Hidden Wealth of Nations, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015). Jane Gravelle, “Tax Havens: International Tax Avoidance and Evasion,” (Washington DC: Congressional Research Service, 2015). Also see the many earlier studies reviewed in Ruud A. De Mooij and Sjef Ederveen, “Corporate Tax Elasticities: A Reader’s Guide to Empirical Findings.” Oxford Review of Economic Policy 24, no. 4 (2008): 680–97. These estimates are also in line with increases in the estimated costs of the tax expenditure of deferral; the Joint Committee on Taxation now estimates this tax expenditure at $83.4 billion for 2014. OMB estimates are somewhat lower, at $61.7 billion in 2014. This represents the estimated revenue cost associated with allowing deferral of the U.S. tax on foreign income until it is repatriated. See Joint Committee on Taxation, Estimates of Federal Tax Expenditures for FY 2014-2018, available at https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=4663 and Office of Management and Budget, FY2016 Analytical Perspectives of the U.S. Government, https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/ default/files/omb/budget/fy2016/assets/spec.pdf.

28. Altshuler and Grubert, “Fixing the System: An Analysis of Alternative Proposals for the Reform of International Tax”; Gravelle, “Moving to a Territorial Income Tax: Options and Challenges”; Leslie Robinson, “Testimony of Leslie Robinson Before the United States Senate Committee on Finance Hearing on International Corporate Taxation,” (Washington, DC: U.S. Senate Committee on Finance, July 22, 2014).

29. See Josh Bivens, “The Data Show Little Need to Increase our Coddling of Corporate Profits,” (Washington, DC: Economic Policy Institute, 2015), http://www.epi.org/publication/the-data-show-little-need-to-increase-ourcoddling-of-corporate-profits/ for a picture based on profit rates; profits are as high as they have been at any point since the 1960s, either pre or post-tax. Similar conclusions hold if one looks at after-tax corporate profits as a share of GDP; see BEA data on corporate profits.

30. The United States has 22.4% of world GDP in 2014 (in dollar terms; we have even less if converted into purchasing power terms to account for different prices levels in different countries). In comparison, we have 28.9% of the world’s biggest firms (our count relative to the Global 2000), 30.7% by sales of such firms, 35.3% of profits of such firms (this is consolidated; it does not say how much profit ends up in the U.S. tax base), 23.8% of assets, and 41.5% of market capitalization.

31. See, for example, Kleinbard, “Competitiveness Has Nothing to Do With It.”

32. J. Clifton Fleming, Robert J. Peroni, and Stephen E. Shay, “Designing a U.S. Exemption System for Foreign Income When the Treasury Is Empty,” Florida Tax Review 13, no. 8 (2012): 397–460.

33. J. Clifton Fleming, Robert J. Peroni, and Stephen E. Shay, “Territoriality in Search of Principles and Revenue: Camp and Enzi.” Tax Notes 14, no. 173 (2013), http://ssrn.com/abstract=2340615.

34. See Department of Treasury, “General Explanations of the Administration’s Fiscal Year 2016 Revenue Proposals,” (Washington, DC: Department of the Treasury, 2015), https://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/taxpolicy/Documents/General-Explanations-FY2016.pdf.

35. See OECD, “BEPS 2015 Final Reports,” OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting ( Paris: OECD Publishing, 2015), http://www.oecd.org/ctp/beps-2015-finalreports.htm.

36. U.S. corporations could be disallowed from moving abroad for tax purposes if they remained managed and controlled in the United States or if the corporation did not do significant business in the country it claims as its new home.

37. Since one of the key drivers behind inversions is facilitating the subsequent shifting of income out of the U.S. tax base, tightening these rules would reduce the lure of inversion. For a catalog of many of the previous proposals to tighten these rules, see Marty Sullivan, “The Many Ways to Limit Earnings Stripping.” Tax Notes 144, no. 377 (2014).

38. For elaboration, see Dan Shaviro, “Understanding and Responding to Corporate Inversions,” Start Making Sense Blog, July 28, 2014, http://danshaviro.blogspot.com/2014/07/understanding-and-responding-to.html. Shareholders still pay capital gains taxes under typical inversion deals since the merger creates a realization event, but exit taxes would affect tax at the corporate level. Of course, many capital gains are not taxed at the individual level, if the shareholder is tax-exempt (e.g.,nonprofits, pensions, and annuities).

39. Some sections of text describing these larger reforms is excerpted from Kimberly A. Clausing, “Beyond Territorial and Worldwide Systems of Taxation.” Journal of International Finance and Economics 15, no. 2 (2015): 43–58.

40. See Joint Committee on Taxation, “Present Law and Issues in U.S. Taxation of Cross-Border Income,” (Washington DC: Joint Committee on Taxation, September 9, 2011), https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=4355. Edward D. Kleinbard, “The Lessons of Stateless Income,” Tax Law Review 65 no. 1 (2011): 99–171. Reuven S. Avi-Yonah, “Hanging Together: A Multilateral Approach to Taxing Multinationals,” Law and Economics Working Paper 116, (Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan, 2013), http://repository.law.umich.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1226&context=law_econ_current. The regime would only apply to U.S. corporate shareholders of foreign subsidiaries. One pragmatic issue concerns the degree of ownership that would act as a threshold for the required consolidation: options discussed by Joint Committee on Taxation include 80%, 50%, and 10%.

41. For firms with excess tax credits, there would still be an incentive to avoid earning income in high-tax countries and to earn income in low-tax countries. Excess tax credits are only likely if the average effective foreign income tax rate exceeds the residence country tax rate.

42. See, for example, Daniel Shaviro, “The Rising Tax-Electivity of US Corporate Residence.” Tax Law Review 64, no. 3 (2011): 377–430.

43. Kleinbard, “The Lessons of Stateless Income”; Avi-Yonah, “Hanging Together: A Multilateral Approach to Taxing Multinationals.”

44. Avi-Yonah, “Hanging Together: A Multilateral Approach to Taxing Multinationals.”

45. See, for example, Reuven S. Avi-Yonah and Kimberly A. Clausing, “Reforming Corporate Taxation in a Global Economy: A Proposal To Adopt Formulary Apportionment” in Path to Prosperity: Hamilton Project Ideas on Income Security, Education, and Taxes, edited by Jason Furman and Jason E. Bordoff, 319–344, (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 2008). As an example, if a multinational company earned $1 billion worldwide, and had 30% of their payroll and assets in the United States, but 60% of their sales in the United States, their U.S. tax base would be $400 million under an equal weighted formula ((.3+.3+.6)/3) * $1 billion), and $600 million under a single sales formula ((.6) * $1 billion).

46. This assumes that the multinational firm has a taxable presence (i.e., nexus) in the locations where it has employment, assets, and sales.

47.

Emmanuel Saez, Joel Slemrod, and Seth H. Giertz, “The Elasticity of Taxable Income with Respect to Marginal

Tax Rates: a Critical Review,” Journal of Economic Literature 50, no. 1 (2012): 3–50. Joel Slemrod and Jon Bakija, Taxing Ourselves, (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2008). Alan J. Auerbach and Joel Slemrod, “The Economic Effects of the Tax Reform Act of 1986.” Journal of Economic Literature 35, no. 2 (1997): 589–632.

48. This is particularly the case for final goods. For intermediate goods, this is more problematic.

49. For an in-depth analysis of this question, see Kimberly A. Clausing, “The U.S. State Experience Under Formulary Apportionment: Are There Lessons for International Taxation.” National Tax Journal (forthcoming, June 2016). Whether this tax-insensitivity would hold at higher corporate tax rates is an empirical question. Still, the forces of tax competition (mobility of production, competitive pricing, etc.) are likely stronger between U.S. states than between foreign countries.

50. This also generates the potential for double-taxation or double non-taxation, although this is also a problem under the present system.

51. There is a natural incentive for countries to follow suit, as discussed in Avi-Yonah and Clausing, “Reforming Corporate Taxation in a Global Economy.” In particular, once some countries adopt formulary apportionment, remaining separate accounting (SA) countries would lose tax base, since income can be shifted away from SA countries to FA countries without affecting tax burdens in FA locations (since they are based on a formula).

52. This work includes: Avi-Yonah and Clausing, “Reforming Corporate Taxation in a Global Economy”; Reuven S. Avi-Yonah, Kimberly A. Clausing, and Michael C. Durst, “Allocating Business Profits for Tax Purposes: A Proposal to Adopt a Formulary Profit Split.” Florida Tax Review 9 (2009): 497–553. The later paper suggests a formulary profit-split method. The tax base would be calculated as a normal rate of return on expenses, with residual profits allocated by a sales-based formula. With careful implementation, such an approach might lessen concerns regarding tax competition under a formulary approach.

53. Over 50% of individual passive income is held in tax-exempt form through pensions, retirement accounts, life insurance annuities, and non-profits, and new evidence suggests that perhaps as little as 25% of U.S. equities are held in accounts that are taxable by the U.S. government. See an upcoming working paper by Leonard Burman and co-authors, as well as Jane G. Gravelle and Thomas L. Hungerford, “Corporate Tax Reform: Issues for Congress” (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, 2012).

54.

This is confirmed by several different sources, documented in Margaret Jacobson and Felippo Occhino, “Labor’s Declining Share of Income and Rising Inequality,” Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland Economic Commentary, September 25, 2012, https://www.clevelandfed.org/newsroom-and-events/publications/

economic-commentary/2012-economic-commentaries/ec-201213-labors-declining-share-of-income-and-risinginequality.aspx. Data from the BEA, the BLS, and the CBO confirm these trends. While these three separate data sources employ different measures of labor’s share, they all confirm this decline in recent decades. Data from the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis show labor’s share declining from about 67% to about 64% over a recent decade, data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics show the share declining from about 63% to 58% (from the early 1980s to recently), and data from the Congressional Budget Office show labor’s share of income decreasing from 75% in 1979 to about 67% in 2007.

55. Corporate taxes fall primarily on shareholders and capital-owners, not workers. For extensive evidence and discussion, see Kimberly A. Clausing, “In Search of Corporate Tax Incidence.” Tax Law Review 65, no. 3 (2012): 433–72; Kimberly A. Clausing, “Who Pays the Corporate Tax in a Global Economy?” National Tax Journal 66, no. 1 (2013): 151–84. And even if the corporate tax were to fall partially on labor, it is important to remember that most alternative tax instruments to finance government fall entirely on labor.

56. Without a corporate tax, the corporate form can provide a tax-sheltering opportunity, particularly for high-income individuals. Sheltering opportunities exist when corporate rates fall below personal income tax rates and corporations retain a large share of their earnings. See Gravelle and Hungerford, “Corporate Tax Reform: Issues for Congress.”

57. In models with real world features such as finitely-lived households, bequests, imperfect capital markets, and savings propensities that correlate with earning abilities, capital taxation has an important role to play in an efficient tax system.