Pro-growth tax reform in 2025 would boost the U.S. economy for years to come

In the aftermath of the presidential election in 2024, it’s clear that many Americans feel like the U.S. economy is not working for them. Even though policymakers on both sides of the aisle have promised to improve people’s living standards, a lot depends on the outcome of one important debate this year.

In 2025, many provisions of the Trump-era tax cuts are set to expire. What Congress does in response could make a real difference in whether the United States has robust economic growth in the coming years.

Beginning as soon as this month, Congress may start to debate whether and how to extend the expiring provisions of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. This law delivered large benefits to wealthier people and to corporations under the old (and oft disproven) theory that tax cuts for those at the top of the income distribution would “trickle down” and spur stronger economic growth. Instead, by most accounts, those tax cuts were a disaster for the economy: They added $2 trillion to the national debt and did not benefit the vast majority of Americans.

So, who did benefit? The research shows that nearly all of the $1.3 trillion in C-corporation tax cuts benefited high-income executives and shareholders, not working families. The tax reform debate presents an opportunity not only to address the expiring provisions of that law, but also to reimagine how the tax code can actually foster shared prosperity and a thriving economy.

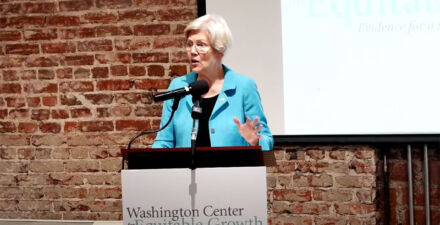

In a recent report, I and my Equitable Growth colleagues Michael Linden and David S. Mitchell outline the academic evidence that a well-designed tax code can yield equitable economic growth and help secure an economy that works for more people. (See the video below for a brief overview of our report’s findings and the stakes of this debate.)

There are three main ways that progressive and pro-growth reform could ensure broadly shared economic growth. First, progressive taxes would help reduce the economic drag of extreme concentrations of wealth and income. Excessive inequality is itself a barrier to strong and durable growth. Inequality obstructs the supply of people and ideas into the economy and limits opportunity for those not already at the top, both of which slow productivity growth over time.

In addition, inequality distorts economic demand, siphoning resources away from the broad middle-class consumer base. In fact, economist Alan Krueger estimated that because of increasing inequality between 1979 and 2007, aggregate consumption was about $440 billion lower every year than it would have been if lower-income consumers had grown more prosperous. And when everyday consumers do not have as much money to spend, businesses are less incentivized to make robust investments. Taxes can be used to reduce inequality and remove those barriers to inclusive growth.

Second, taxes generate revenue that can be used to fund growth-enhancing public investments, such as universal child care and climate change mitigation, and to reduce long-term fiscal risks. Indeed, returns to the greater economy from public investment in children alone are significant, with some programs returning $10 for every $1 invested in children back to society. Lack of revenue, conversely, can lead to underinvestment and a riskier fiscal trajectory. The United States has a lower revenue-to-GDP ratio than any other country in the Group of Seven peer leading industrial nations and taxes well below the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development average. A stronger tax code that generates more revenue could address underinvestment and fiscal trajectory challenges.

Third, taxes can encourage productive economic behavior and address market distortions and inefficiencies that diminish growth. For example, when extremely large companies use their power in the marketplace to extract extra profits far beyond what they could earn through fair competition, tax cuts for those companies only serve to reward and incentivize that behavior. That may be good for that one company’s bottom line, but it is bad for the economy as a whole because it leads to less innovation, less competition, and less dynamism. The tax code could remove incentives to accumulate the most power in a marketplace and instead reward companies that genuinely have the best ideas, the most productive workers, or the most innovative business practices.

There are many important issues at stake in the coming tax fight, but at the heart lies this question: Will we once again cut taxes for the rich, or will we raise taxes on the rich to help the rest of society and the overall economy? The answer to that question will have an outsized impact on the U.S. economy for decades to come.

Did you find this content informative and engaging?

Get updates and stay in tune with U.S. economic inequality and growth!