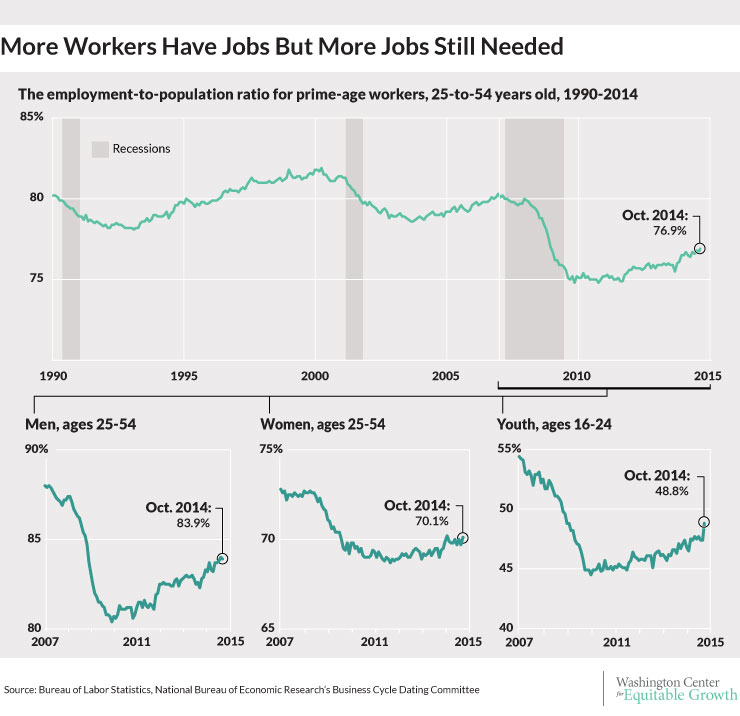

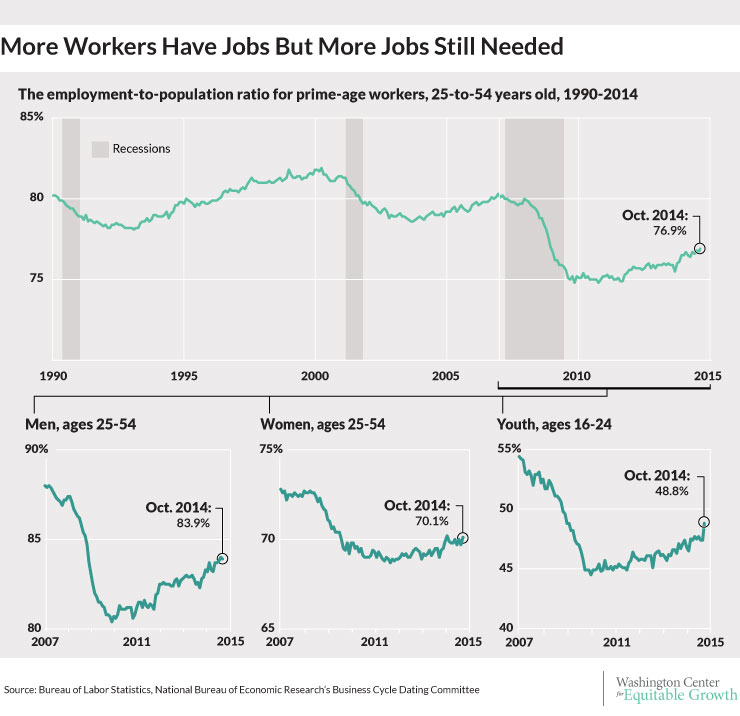

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics today released their latest employment figures, which showed continuing jobs gains in October but with wage growth remaining weak. The share of prime-age workers (ages 25 to 54) with jobs rose 0.2 percentage points to 76.9 percent. Over the past three months, job growth averaged about 224,000 per month. But nominal wages (before factoring in inflation) only increased at an annual rate of 2.0 percent over the past quarter. This continuing inability to translate jobs gains into wage growth highlights the presence of slack in the U.S. economy, one of the reasons growing income inequality seems to be so stubbornly entrenched.

Starting with the job gains, prime-age working women with jobs rose 0.4 percentage points last month to 70.1 percent, compared to 69 percent a year ago. Employment for prime-age men, however, remained relatively unchanged. The overall employment-to-population ratio for prime-age workers is now 1.5 percentage points higher than it was last year, yet it remains 4.4 percentage points lower than its prior peak more than seven years ago, before the start of the Great Recession in December 2007. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

Perhaps the brightest spot in the jobs numbers released today was youth employment, which improved significantly. The share of workers ages 16 to 24 with jobs rose 1.4 percentage points in October. The employment-to-population ratio for young workers is now 48.8 percent, the highest rate for this age group in the past five years. At the same time, the youth employment needs substantial gains in order to reach its prior peak of 54.8 percent in 2006, let alone its high of 59.9 percent in 2000. Employment for 16-to-24 year-old workers never recovered from the 2001 recession, and then suffered steep losses again in the most recent recession.

The wage figures released today remain disheartening as nominal wages continue to increase at the less than satisfactory annual rate of 2.0 percent. We will not see sustained real wage growth until nominal average wages reliably increase at an annual rate of more than 3.5 percent, assuming the Federal Reserve’s target inflation rate of 2.0 percent and productivity growth of 1.5 percent. Nominal wage growth has been below the 3.5 percent threshold for more than five years.

Employment growth by sector was strongest in services industries. Much of the employment growth in October came from restaurants, with nearly 42,000 jobs added last month, and the retail sector, which increased by about 27,000 jobs. Both restaurants and the retail trade sector rely substantially on minimum wage workers—one reason real wage growth remains anemic across the country. Restaurant employment is up by about 3.1 percent over the past year, whereas retail grew by about 1.6 percent. In contrast, government employment remained essentially unchanged last month. For the overall private sector, average weekly hours increased slightly to 34.6 hours.

The employment gains from the October report are positive, but continued anemic wage growth is consistent with considerable weakness in the U.S. labor market. In addition, the latest economic growth statistics do not suggest we will make sustained improvements in eliminating the slack from the Great Recession, as the U.S. economy is not expected to rely on increased government spending and net exports. Until policymakers steer our economy toward more sustainable growth, broad-based real income gains for the vast majority of workers will remain elusive.