This is a weekly post we publish on Fridays with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth has published this week and the second is work we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

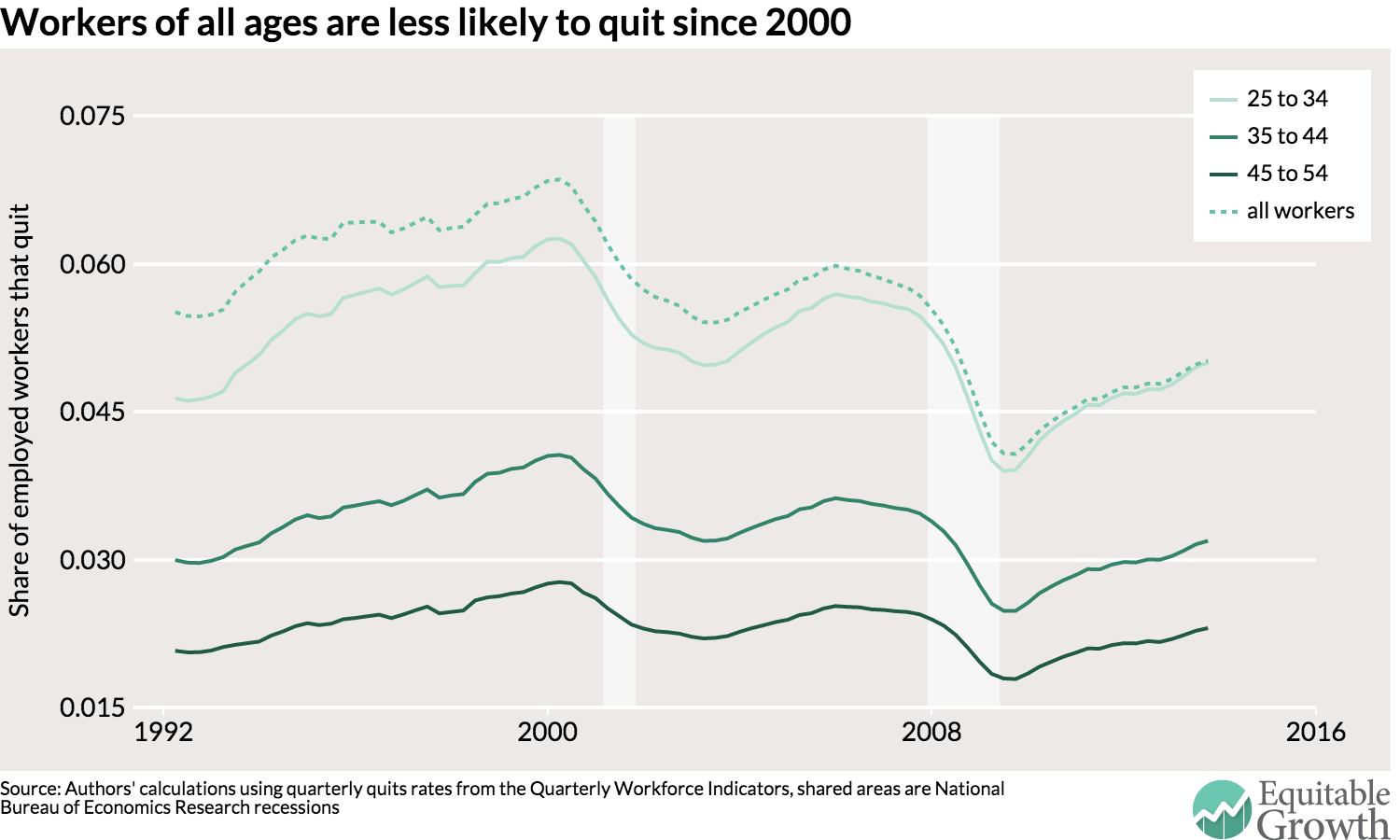

Job-to-job mobility in the U.S. labor market has been on the decline for the past 15 years. Over that time period, the country’s population has also aged quite a bit as the Baby Boomers started retiring. But how much of the decline in quitting is due to demographics? Not much.

The Federal Reserve is certainly aware of racial inequality in the United States as well as other forms of inequality. But how much does that awareness count for unless the central bank conducts policy in an inequality-aware manner?

Walmart recently announced it’s closing more than 100 stores across the country, and not expanding stores it previously promised in the District of Columbia. Heather Boushey uses this occasion to point out that low wages aren’t always competitive.

Paid leave programs have support from presidential candidates on both sides of the aisle and have proven benefits for workers. And new research shows that businesses seem to like them as well. But why is that?

Links from around the web

Central bankers have long focused on just cyclical (short-run) changes in the economy. But monetary policymakers are increasingly focusing on a number of structural (long-run) changes. Gertjan Vlieghe, a member of the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee, focuses on three trends: debt, demographics, and the distribution of income. [bank of england]

Real weekly earnings growth in the United States has picked up over the past two years after being flat for most of the recovery from the Great Recession. But what has driven this bump in earnings growth? Jared Bernstein decomposes it to find the sources. [on the economy]

U.S. cities with high levels of inequality also tend to be cities where low-income households spend more on rent. In other words, inequality is correlated with a lack of affordable housing. Emily Badger investigates what might explain this relationship. [wonkblog]

The return to additional capital investment—or, in economics terms, “the marginal product of capital”—seems to be on the decline in the United States since the 1960s. Does that mean we’re entering a period of secular stagnation? Or that the marginal product is returning to its old historical value? Dietz Vollrath looks at the data. [growth economics]

Business dynamism in the United States is also on the decline. Americans are less likely to start a company, and new firms are growing slower than in the past. Noah Smith reports on new research, however, that finds federal regulations aren’t the root of the problem. [bloomberg view]

Friday figure

Figure from “Demographics don’t explain the decline in quitting” by Nick Bunker and Kavya Vaghul.