…The first snippet in this compilation.. posed the question ‘Exchange and its vicissitudes as fundamental to human psychology and society?’ and followed that with a justly famous quotation from Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations…. Brad’s question zeroed in on some crucial issues. I was provoked to start writing a message… I thought would run a few lines… but it turned out to be a little longer, so I might as well share it.

Hi Brad,

Your post with ‘Snippets: Smith, Marx, Solow: Shoebox’ for Econ 210a Spring 2014 (‘Exchange and its vicissitudes as fundamental to human psychology and society?’) begins by quoting one of Smith’s most theoretically important passages in The Wealth of Nations. That passage (from the second chapter in Book I of WN) also contains one of Smith’s most impressive, and cleverly deceptive, bits of conceptual and rhetorical sleight-of-hand. Too many readers, including quite sophisticated ones, uncritically accept this conceptual sleight-of-hand and take it at face value. Perhaps even Brad DeLong is one of them? I notice that you actually collude in the deception (no doubt unintentionally) by selectively quoting from that passage.

Nobody ever saw a dog make a fair and deliberate exchange of one bone for another with another dog…. When an animal wants to obtain something either of a man or of another animal, it has no other means of persuasion but to gain the favour of those whose service it requires. A puppy fawns upon its dam, and a spaniel endeavours by a thousand attractions to engage the attention of its master who is at dinner, when it wants to be fed by him. Man sometimes uses the same arts with his brethren, and when he has no other means of engaging them to act according to his inclinations, endeavours by every servile and fawning attention to obtain their good will. He has not time, however, to do this upon every occasion. In civilised society he stands at all times in need of the cooperation and assistance of great multitudes, while his whole life is scarce sufficient to gain the friendship of a few persons….

[Hum]an has almost constant occasion for the help of his brethren, and it is in vain for him to expect it from their benevolence only. He will be more likely to prevail if he can interest their self-love in his favour, and show them that it is for their own advantage to do for him what he requires of them. Whoever offers to another a bargain of any kind, proposes to do this. Give me that which I want, and you shall have this which you want, is the meaning of every such offer; and it is in this manner that we obtain from one another the far greater part of those good offices which we stand in need of. It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest. We address ourselves, not to their humanity but to their self-love….

Let’s start with those dogs, since that’s where the deceptive argumentation begins, and a more careful examination of what Smith says about dogs already begins to undermine his carefully constructed dichotomy. Sure, it’s probably true that nobody ever saw two dogs exchange bones of equivalent value. (Why would they want to do that?) But so what? That point is just a distraction from the real question. The central agenda of this passage is to argue that the only two ways to get help or assistance from someone else are (a) self-interested exchange or (b) an appeal to their ‘benevolence’ by begging and ‘fawning’. Let’s forget humans for a moment. Is that second option the only way dogs ever do it?

Smith wants us to think the answer is yes, but the answer is obviously no. To see why, we should pay attention to what happens in the three sentences immediately preceding the quotation. Smith, in effect, denies that dogs (and presumably other canine species) hunt in packs. If you think I’m making that up, go back and re-read the relevant sentences.

Two greyhounds, in running down the same hare, have sometimes the appearance of acting in some sort of concert. Each turns her toward his companion, or endeavours to intercept her when his companion turns her toward himself. This, however, is not the effect of any contract, but of the accidental concurrence of their passions in the same object at that particular time.

No, dogs don’t trade one bone for another. But dogs and other animals definitely do cooperate (not just in pairs, but in packs) in obtaining things they could not obtain, or achieving things they could not achieve, as individuals. In the process of cooperation, they help each other out. And they regularly do so in ways that do not involve market exchange (or servile fawning).

It’s probably correct to say that two dogs pursuing a hare together haven’t made a ‘contract’ (that would depend, in part, on precisely what Smith means by ‘contract’ here). But is that logically equivalent to claiming, as Smith implies by a cunning conceptual slide, that the two dogs aren’t really acting in ‘concert’? A moment’s reflection should be sufficient to make the answer embarrassingly obvious. In the real world, dogs—and other animals—frequently act in concert.

OK, perhaps Smith didn’t know dogs that well. (Actually, I suspect that’s not so, but let’s just concede the possibility.) But humans can hunt in packs, too, and do lots of other things in packs. Humans act in concert all the time, in ways that are not based on trucking and bartering. That may seem like an obvious fact, once it’s pointed out … but a major purpose of Smith’s discussion in the first several pages of that chapter is to obscure the theoretical significance of this obvious fact.

Why would Smith want to obscure that conceptual point?

We don’t need to try to read Smith’s mind, but we do know that Smith is a careful analytical system-builder and a writer of great rhetorical skill and sophistication. (His writings on rhetoric are justly admired.) And one can’t help noticing that obscuring, or evading, that conceptual point serves a useful function in helping Smith lay the foundations for his core theoretical argument in WN.

As I’ve already noted, Smith tries hard to convey the impression that the only significant basis for sustained mutually beneficial interaction between individuals is self-interested exchange, which on the one side is rooted in certain basic impulses or motivations built into human nature (self-interest + the impulse to exchange), and on the other side gives rise (unintentionally but intelligibly) to a dynamic system of self-interested exchange (the market) with its own distinctive laws & dynamics. Smith further wants to suggest that the only possible alternative basis for (intermittent) mutual aid or beneficial interaction is gratuitous ‘benevolence’ or (to use a later, 19th-century, word) altruism.

But that’s a false dichotomy, since it implicitly rules out other bases for concerted action and mutually beneficial interaction that do, indeed, play significant roles in real life.

What am I getting at? Well, let’s review the first sentence from the second paragraph you quoted:

[M]an has almost constant occasion for the help of his brethren, and it is in vain for him to expect it from their benevolence only.

Yes, man (or human) does have constant needs for coordinated action, mutually beneficial interaction, and assistance from others. (So do wolves.) And it’s true that gratuitous altruism or ‘benevolence’ cannot serve as the only basis for them, quite aside from the fact that constantly wheedling other people for favors or handouts is demeaning. But are those really the only two alternatives? No, of course not. This is a cleverly constructed, and rhetorically effective, false dichotomy.

Let me step back and point out that, in the most basic analytical terms, there are at least three ways to achieve sustained coordination of human actions—even if we just ignore ‘benevolence’ for the moment. (I emphasize ‘at least’ because this isn’t meant to be a comprehensive or fully systematic typology, just something sufficient to begin moving beyond that false dichotomy.)

(1) One obvious possibility is top-down command, or what we might euphemistically term ‘imperative coordination’ (to use Parsons’s idiosyncratic and somewhat bowdlerizing translation of Weber’s Herrschaft). And in fact this mode of coordination turns up right in Chapter 1 of Book I of WN, since that is precisely how the the division of labor within the famous pin factory is instituted and run. Yes, the rest of WN goes on to show how it is possible to have an effective division of labor (i.e., dynamic systems of simultaneous differentiation and coordination) without the necessity for conscious top-down coordination based on command—i.e., a division of labor can be coordinated by the impersonal system of the self-regulating market—and that’s a brilliant and profound theoretical achievement. But we shouldn’t forget that domination or authority plays a role in social and economic life, too. And, to repeat, the coordination of action within Smith’s pin factory (or any other formal organization) is not based, in principle, on either gratuitous ‘benevolence’ or the self-interested exchange of commodities.

(Marx, of course, hammers that point home with his analysis of the two complementary forms of the division of labor in the capitalist mode of production, and brilliantly spells out some of the implications.)

(2) A second possible mode of coordinating human action is through the market—i.e., an impersonal, dynamic, and self-regulating system of self-interested exchange. Let’s be conceptually clear and precise here. Smith’s point about how the market operates as a system is that it allows tens, thousands, or millions of people to be connected in chains of mutually beneficial interaction without having to consciously coordinate their actions or reach agreements about them, without having to care about what those other people need or want, without even knowing they exist. In so far as those millions of mutual strangers ‘cooperate’ in the market system, that ‘cooperation’ is purely functional and metaphorical. In fact, the beauty of the market is precisely that it allows for systematic and beneficial coordination without the need for either conscious cooperation or conscious top-down ‘imperative coordination’ (i.e., domination).

(3) But that brings us to a third possible mode of coordinating human action, which is conscious cooperation. Humans can sometimes manage to pursue joint or common ends, not through the indirect mechanisms of self-interested exchange of commodities, nor by simultaneously submitting to a common superior who directs and coordinates their actions (the Hobbesian solution), but by engaging in concerted action guided by common agreement, custom, habituation, etc.. Not only can humans do it, even dogs and wolves can do it—despite what Smith’s second paragraph in Chapter 2 of Book I of WN might seem to imply.

Conscious cooperation, by the way, is not identical to gratuitous ‘benevolence’ or altruism. It may draw on emotions of fellow-feeling or solidarity (those frequently help), but it may also entail quite hard-headed calculations of material advantage and instrumental rationality. But the point is that, in this context, the interests of the participants can be pursued, not through exchange, but through actual (not virtual) cooperation. Furthermore, humans sometimes manage to build up complex systems for enabling large-scale and sophisticated forms of cooperation, including institutional mechanisms for collective deliberation and decision-making, representation, etc.

(In the real world, many human practices and institutions involve more or less complex mixtures of elements from more than one of those categories, or even from all three. But for the sake of conceptual clarity, and to avoid the typical conceptual obfuscations, it’s useful to begin by laying out those ideal-typical analytical distinctions sharply. To pretend, or imply, or even tacitly insinuate that option #2 is the only way to coordinate human activity in sustained and beneficial ways—and that the only conceivable alternative is gratuitous ‘benevolence’—is self-evidently wrong.)

And as long as we’re on the subject of the tacit exclusions underlying Smith’s foundational false dichotomy, let me mention just one more factor. Smith suggests in the passage you quoted that if we want someone else to do something that might be necessary or beneficial for us, there are two kinds of motivation, and only two kinds of motivation, that we might appeal to. We can appeal either to their individual self-interest or to their disinterested benevolence. Well, in the real world, we often make claims or recommendations, or have expectations that we regard as sensible and legitimate, based on people’s obligations (moral, legal, customary, religious, or whatever). Obligations are not individual psychological characteristics, but socially structured norms, and they are not simply reducible to motivations of generalized ‘benevolence’ or of the calculation of individual self-interest. (Of course, some people might want to argue for reducing them to the latter—those would be the kinds of ‘rational actor’ obsessives who would tautologically reduce everything to calculations of individual self-interest—but I don’t think I need to spell out to you the reasons why that won’t work. Life is more complicated than that.) Also, it so happens that systems of obligation are of fundamental importance in shaping and coordinating all modes and areas of human social life, from what Smith calls the ‘early and rude state of society’ up to the present. (I suppose that’s a Durkheimian point, though it might also be treated as Burkean or Polanyian.)

=> OK, I could go on … but that should be sufficient to get the main points across.

Smith might well want to argue that coordinating human action through the market, based on the motivations and practices of self-interested exchange (and their indirect and unintended consequences), is (generally speaking, and all things being equal) better and more efficient than coordinating human action through domination, conscious cooperation, obligation, etc. Elsewhere in WN Smith does, in effect, make arguments along those lines. And one could certainly find strong and plausible grounds for them (though I confess to having a soft spot for conscious coordination, where it’s practicable).

However, such arguments would be different from the explicit argument that Smith actually does make in the passage you quoted—i.e., that the only significant basis for the sustained and mutually beneficial coordination of human action is self-interested market exchange … and that the only conceivable alternative would be the throw-away residual category of gratuitous ‘benevolence’ (which present-day mainstream economists usually shove into the even-more-grab-bag residual category of ‘altruism’). The argument that Smith actually makes there is incorrect, is based on an obvious false dichotomy … and has proved to be a brilliantly successful and convincing piece of rhetorical and conceptual sleight-of hand. We should admire the brilliance, but we shouldn’t be taken in.

=> Nor is this a peripheral or merely technical point. One of the central arguments that runs through and structures Smith’s whole discussion in Books I-II of WN is that the market (based on the built-in human motivations and ‘natural’ practices of self-interested exchange) is not just one important basis of social order, but is the fundamental basis of social order (and of the main tendencies of long-term socio-historical development). That’s what it means to treat ‘exchange and its vicissitudes as fundamental to human psychology and society’.

Again, that’s a brilliant, powerful, and fascinating theoretical argument. But it’s wrong… and swallowing it uncritically has led many very intelligent people astray.

Yours for theory,

Jeff Weintraub

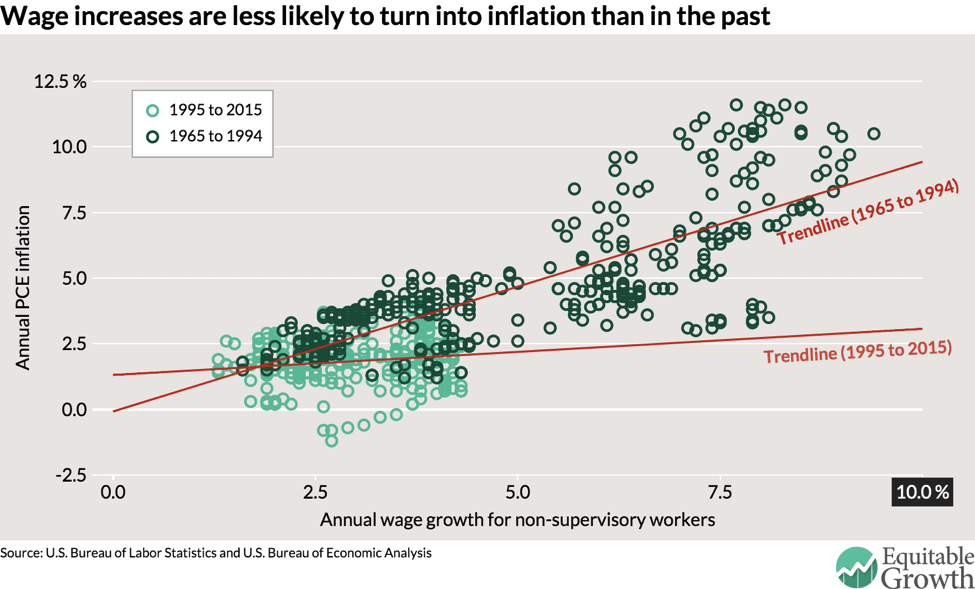

The accelerationist Phillips curve relied upon a relatively strong pass-through between wage growth and inflation. But increasing wages don’t have to go entirely toward boosting the inflation rate—higher wage growth might also result in a higher share of income going to labor. J.W. Mason makes this point quite well in

The accelerationist Phillips curve relied upon a relatively strong pass-through between wage growth and inflation. But increasing wages don’t have to go entirely toward boosting the inflation rate—higher wage growth might also result in a higher share of income going to labor. J.W. Mason makes this point quite well in