- : China’s Exchange-Rate Trap

- (2013): How a Frustrated Blogger Made Expanding Social Security a Respectable Idea

- (2014): Oversharing About Money: An International Financial Wire Transfer from Lafayette, California, USA to Ahero, Nyando District, Nyanza Province, Kenya

- : One Year In: Why A Die-Hard Mechanical Watch Lover Can’t Get The Apple Watch Off His Wrist (And Why That Matters)

Must-read: Richard Mayhew: “The Sovaldi that Wasn’t”

Must-Read: : The Sovaldi that Wasn’t: “Last summer every insurer in the country was rerunning their models on how the next wave of cholesterol drugs…

…were going to blow up the cost structure… inhibitors… priced at over $1,000 per month…. The specific on-label use… were for a… subset… with high cholesterol… genetic markers and clinical indicators…. We got that one wrong…. “A surge in sales of pricey new cholesterol treatments is unlikely to materialize this year, contrary to the previous expectations of Express Scripts Holding, an executive from the largest manager of U.S. drug benefits said on Friday.”…

This is intriguing. It may be a blip or it could be a portent of a significant change in provider behavior. If it is blip, disregard the rest. There is a possibility that providers are becoming price aware…. The big fear with the new inhibitors was that they would be widely prescribed for a much broader population of people than the clinically significant group…. That is the entire point of the pharmaceutrical advertising industry, to get providers prescribing higher cost medications for marginal cases.

Must-read: Dani Rodrik: “The Trade Numbers Game”

Must-Read: I had thought that we understood rather well why freer trade created substantial winners and losers–that the shifts in the prices of goods from moves to freer trade caused magnified shifts in the rewards to factors that were used intensively in the production of such goods. And the consequences for the overall level of employment seem, to me at least, to be limited to the era of “Depression Economics” that we entered in 2007 and from which we have not emerged: NAFTA did not raise unemployment in the United States.

So I find myself failing to grasp large pieces of the very sharp Dani Rodrik’s argument here:

: The Trade Numbers Game: “The Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP)… is the latest battleground in the decades-long confrontation…

…between proponents and opponents of trade agreements…. The pact’s advocates have marshaled quantitative models that make the agreement look like a no-brainer…. There is no disagreement between the models on the trade effects…. The differences arise largely from contrasting assumptions about how economies respond to changes in trade volumes sparked by liberalization. Petri and Plummer assume that labor markets are sufficiently flexible that job losses in adversely affected parts of the economy are necessarily offset by job gains elsewhere…. Capaldo and his collaborators offer a starkly different outlook: a competitive race to the bottom in labor markets…. The Petri-Plummer model is squarely rooted in decades of academic trade modeling…. By contrast, the Capaldo framework lacks sectoral and country detail; its behavioral assumptions remain opaque; and its extreme Keynesian assumptions sit uneasily with its medium-term perspective….

Economists do not fully understand why expanded trade has produced the negative consequences for wages and employment that it has. We do not yet have a good alternative framework to the kind that trade advocates use. But we should not act as if reality has not severely tarnished our cherished standard model….

The uncertainties do not end with macroeconomic interactions. The Petri-Plummer study predicts that the bulk of the economic benefits of the TPP will come from reductions in non-tariff barriers (such as regulatory barriers on imported services) and lower obstacles to foreign investment. But the modeling of these effects is an order of magnitude more difficult than in the case of tariff reductions…

Weekend reading: “What’s the deal with secular stagnation?” edition

This is a weekly post we publish on Fridays with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth has published this week and the second is work we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

The share of men with a job has been on the decline for decades in the United States. Most explanations for this trend focus on forces that affect men during their working years. But new research from Stanford University’s Raj Chetty and his co-workers highlights the influence of one’s boyhood environment on employment later in life.

The fourth report in Equitable Growth’s “History of Technology” series focuses on responsible innovation, a movement during the 1970s fighting for reforms to the research community in the United States. Cyrus Mody—the report’s author and a professor at Maastricht University—shows how those fights are relevant for thinking about innovative growth today.

Who pays a tax? The answer may not be as simple as whom the tax was placed upon. The incidence of a tax depends on how elastic the supply of and the demand for the good or service is. The example of a proposed oil tax may be illuminating.

The U.S. economy has a tale of two wage growth statistics going on right now. Nominal wage growth is subpar, but inflation-adjusted wage growth looks solid. Which statistic tells us more about the health of the labor market? Here’s an argument for focusing on nominal growth.

When a worker loses a job, they have to find a way to cushion the blow of losing their main source of income. Credit can help them bridge that gap. And increased access to credit can help them search for a higher-paying job than they would have found otherwise.

Yesterday marked the launch of “Equitable Growth in Conversation,” our new series of talks with economists and social scientists. The first installment is an interview with Larry Summers by Heather Boushey about secular stagnation and the role of economic inequality.

Links from around the web

The Great Recession has caused many rethinks in economics and spurred many research agendas. The role of fiscal policy in fighting recessions is an important example of shifting thinking in the wake of the recession. Adam Ozimek takes a look at what we’ve learned and what we still need to dig into. [datapoints]

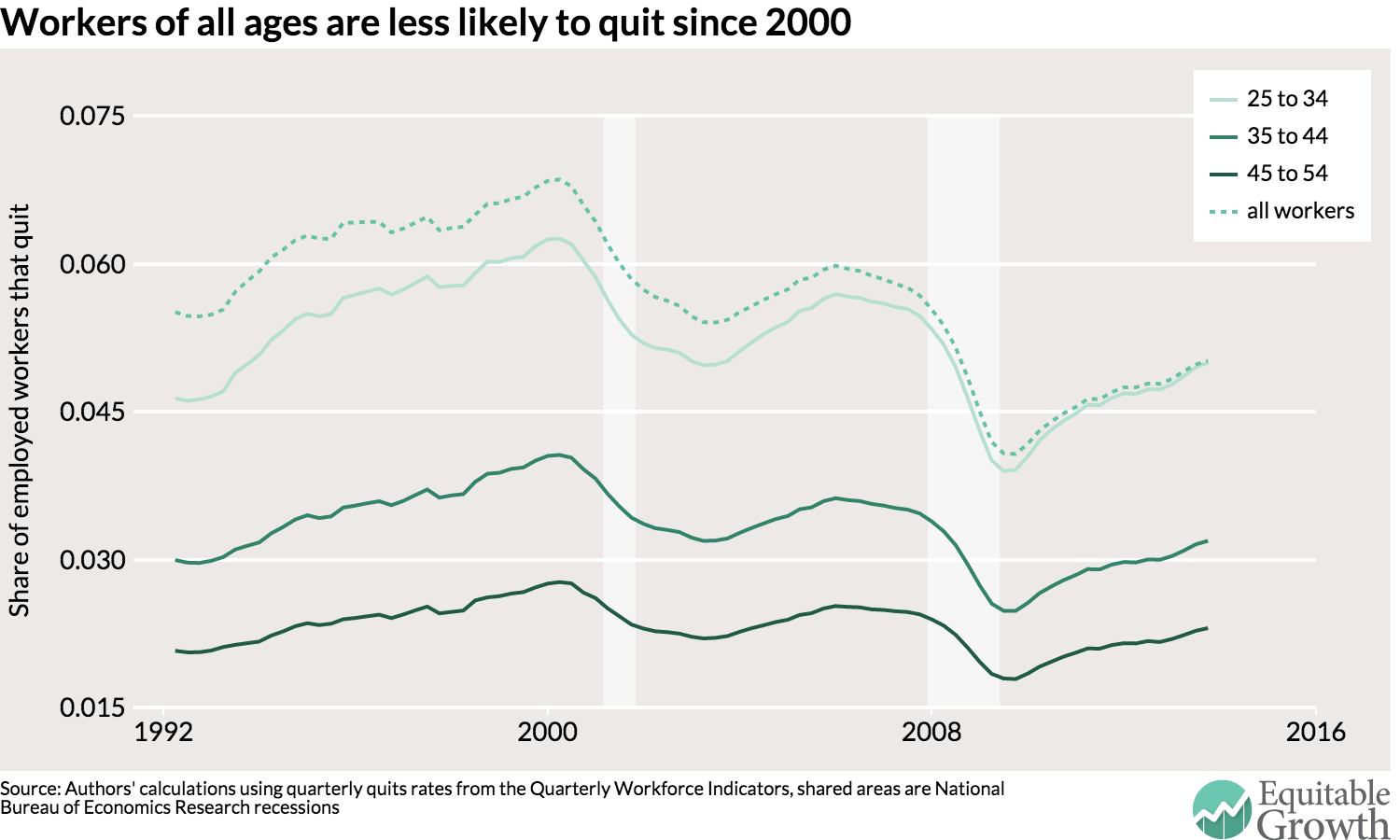

This week’s release of data about labor market flows in December sparked optimism about the U.S. labor market. Workers are seemingly quitting their jobs at rates not seen since before the Great Recession—a sign of a healthier labor market. But Dean Baker argues we shouldn’t be satisfied until the rate has exceeded its old peak for a while. [beat the press]

One of the criticisms of the idea that increasing housing supply can increase housing affordability is that the housing being built is just for high-income residents. But evidence from the Bay Area indicates that lower-income neighborhoods with more housing construction saw less displacement than similar neighborhoods with less construction. Emily Badger reports. [wonkblog]

Negative interest rates are weird, to say the least. The advent of this heretofore impossible situation has sparked some really big questions about the role of the financial system and even the definition of money. Neil Irwin takes a look at the world on the other side of the monetary looking glass. [the upshot]

Negative interest rates—now that we know they are possible—may be the answer to how to ease monetary policy in our current environment. Narayana Kocherlakota, former president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, argues they are appropriate right now. But their necessity is an indictment of fiscal policymakers. [thoughts on policy]

Friday figure

Figure from “Demographics don’t explain the decline in quitting” by Nick Bunker and Kavya Vaghul

Must-read: Richard Mayhew: “The Hope of [Health Care Cost] Stabilization”

Must-Read: : The Hope of [Health Care Cost] Stabilization: “We knew that there was going to be a massive amount of catch-up [health] care…

…as people who either were uncovered, sporadically covered or had no usable insurance because the cost sharing was atrocious got coverage through either Medicaid expansion or the Exchanges. The big question was always how much catch up care was happening and if/when would it subside as crisis care converted into maitenance care. There is starting to be some evidence that the catch up care wave is subsiding…. This uncertainty about catch-up care was why there were the three R’s of risk adjustment, risk corridors and re-insurance. No one knew how many expensive surprises were out there.

Must-reads: February 12, 2016

Must-read: Robert Axtell (2005): “The Complexity of Exchange”

Must-Read: (2005): The Complexity of Exchange: “The computational complexity of two classes of market mechanisms is compared…

…First the Walrasian interpretation in which prices are centrally computed by an auctioneer. Recent results on the computational complexity are reviewed. The non-polynomial complexity of these algorithms makes Walrasian general equilibrium an implausible conception. Second, a decentralised picture of market processes is described, involving concurrent exchange within transient coalitions of agents. These processes feature price dispersion, yield allocations that are not in the core, modify the distribution of wealth, are always stable, but path-dependent. Replacing the Walrasian framing of markets requires substantial revision of conventional wisdom concerning markets.

Why don’t we have a better press corps yet?

I am beginning to think that the highly-estimable Kevin Drum needs his meds adjusted–not those affecting the rest of his body, those seem to going better than I had expected, but rather those affecting his neurotransmitter levels. For he fears to be descending into shrill unholy madness…

I feel his pain. I, too, had hoped that the coming of independent webloggers giving an unmediated public-sphere voice to those with substantive policy knowledge, plus the arrival of the Matt Yglesiases, Ezra Kleins, Nate Silvers, and so on who were interested in making the world a better place through policy-oriented explainer and data journalism would shame the press corps into behaving better.

But no: it’s still, overwhelmingly, horse-race coverage, and bad horse-race coverage, by those who have not even learned how to assess horseflesh, jockey skill, and the track:

: Republican Tax Plans Will Be Great for the Ri—zzzzz: “Our good friends at the Tax Policy Center…

…have now analyzed—if that’s the right word—the tax plans of Donald Trump, Jeb Bush, and Marco Rubio. You can get all the details at their site, but if you just want the bottom line, you’ve come to the right place…. Unsurprisingly, they’re all about the same: middle income taxpayers would see their take-home pay go up 3 or 4 percent, while the rich would see it go up a whopping 10-17 percent. On the deficit side of things, everyone’s a budget buster. Rubio and Bush would pile up the red ink by $7 trillion or so (over ten years) while Trump would clock in at about $9 trillion. That compares to a current national debt of $14 trillion.

No one will care, of course, and no one will even bother questioning any of them about this. After all, we already know they’ll just declare that their tax cuts will supercharge the economy and pay for themselves. They can say it in their sleep. Then Trump will say something stupid, or Rubio will break his tooth on a Twix bar, and we’ll move on.

Unemployment rate truthers department

The very sharp Kevin Drum gets it largely right:

: U6 Is Now the Last Refuge of Scoundrels: “Tuesday Donald Trump repeated his fatuous nonsense about the real unemployment rate being 42 percent….

…Then Neil Irwin of the New York Times inexplicably decided to opine that ‘he’s not entirely wrong’ because there are lots of different unemployment rates. Et tu, Neil?

Bill O’Reilly picked up on this theme today, with guest Lou Dobbs casually declaring that unemployment is ‘actually’ 10 percent… [and] Bernie Sanders… ‘Who denies that real unemployment today, including those who have given up looking for work and are working part-time is close to 10 percent?’… The 10 percent number is colorably legitimate… U6… unemployment plus folks who have been forced to work part time plus workers who are ‘marginally attached’….

But you can’t just toss this out as a slippery way of making the economy seem like it’s in horrible shape…. What’s normal in an expanding economy is about 8.9 percent…. The US economy is not a house afire…. I’m getting pretty tired of the endlessly deceitful attempts to make it seem as if we’re all but on the edge of economic Armageddon, and the last thing we need is for liberals to sign up for this flimflam too. It’s good politics, I guess, but it’s also a lie.

There are two arguments you can make that are not lies but are, rather, coherent arguments that are more likely than not true:

- That the US labor market performs abysmally at the low-wage end essentially all the time, as evidenced by U6.

- that the unemployment rate is a misleading indicator today because of the long-run disruptions to the labor market occasioned by what we must soon start calling “The Longer Depression”, as evidenced by the divergence in the behavior of unemployment and the employment-to-population ratio. And, no, this divergence is not primarily due to population aging.

Thus I think the Sanders conclusion–that the U.S. labor market is not performing all that well right now–is more likely than not to be correct. I object to the road he claims to reach it by. And I join Kevin Drum in doubly objecting to Trump and Irwin.

Must-read: Tim Duy: “Fed Yet to Fully Embrace a New Policy Path”

Must-Read: : Fed Yet to Fully Embrace a New Policy Path: “The Fed will take a pause on rate hikes. An indefinite pause…

…The sooner they admit this, the better off we will all be. Indeed, the sooner they admit this, the sooner financial markets will calm and the sooner they would be able to resume hiking rates. Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen had two high profile opportunities this week to make such an admission. Yet she failed to do so….

By the end of 2015, the economy was near full-employment…. A combination of factors would work in tandem to slow activity… higher dollar, higher inflation, higher wages, and higher short term interest rates (tighter monetary policy). How much monetary policy tightening is consistent with the new equilibrium depends on the evolution of the other prices. A reasonable baseline at the end of last year was that 100bp of tightening would be consistent with achieving full-employment. That was the Fed’s starting point as well….

A key factor in keeping the US economy on the rails is acknowledging that tightening financial conditions via the dollar obviates the need to tightening conditions via monetary policy…. But the Fed has yet to fully embrace this story. And that leaves them sounding relatively hawkish…. Yellen & Co. don’t need to emphasize the direction of rates. They just can’t stop themselves. Worse yet, they feel compelled to describe the level of future rates via the Summary of Economic Projections. A level entirely inconsistent with signals from bond markets, no less. They don’t really know what the terminal fed funds rate will be, so why keep pretending they do? The ‘dot plot’ does nothing more than project an overly-hawkish policy stance that leaves market participants persistently fearful a policy error is in the making. It is time to end the ‘dot plot.’