The employment consequences of increasing the minimum wage in the United States continue to be a major subject of debate, but how researchers choose to estimate the effects of raising the minimum wage can substantially affect the results of their work. In “Credible research designs for minimum wage studies”, my coauthors and I examine one group of low-wage workers—teenagers—whose hourly wages are significantly raised by minimum wage increases.

Download File

Issue Brief: Credible research designs for minimum wage studies

A common objection to raising minimum wages is that doing so will reduce the employment opportunities of low-skilled workers such as teenagers. We show, however, that some studies find negative effects of the minimum wage on teen employment because they fail to control for other economic factors that independently reduced employment around the time of a minimum wage increase. After controlling for these factors, we demonstrate that the large, negative effect on teen employment disappears.

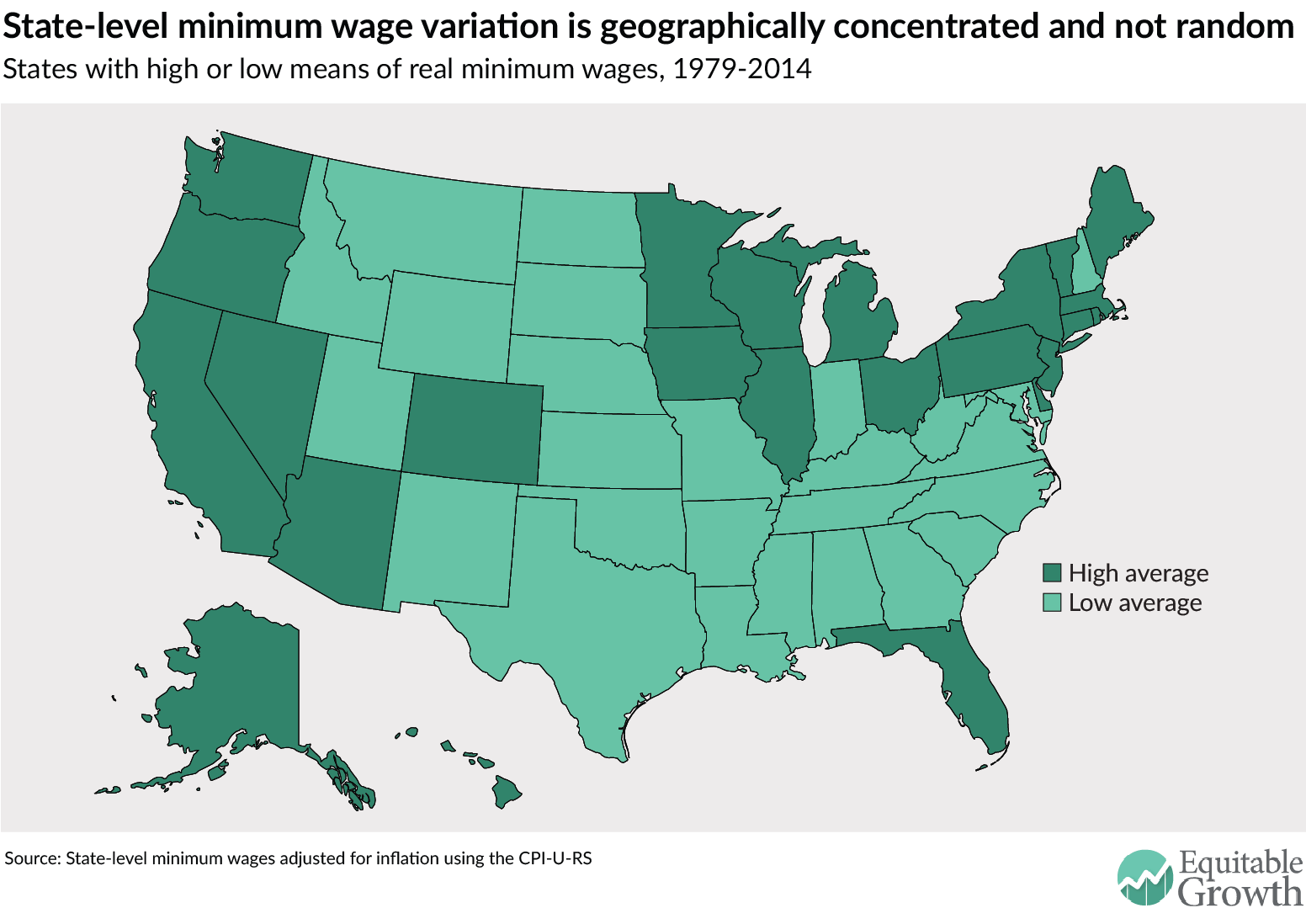

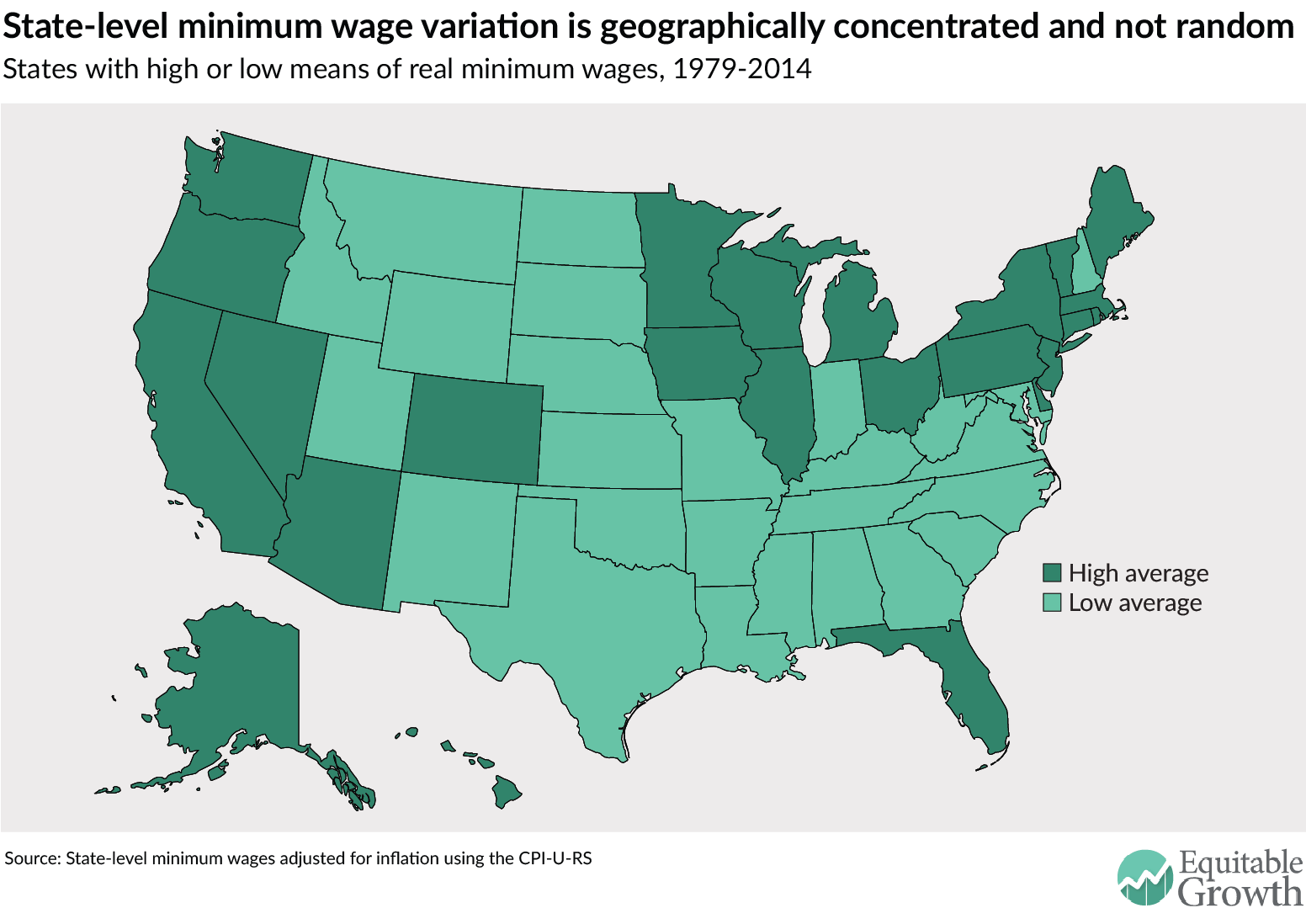

State minimum wage increases are heavily concentrated in different regions of the country

After the frequency of federal minimum wage increases slowed during the 1980s and 1990s, many states began experimenting with setting their own wage floors above the federal level. By last year, more than half of all states had a minimum wage higher than the federal floor. This extensive history of state-level policies offers an attractive set of experiences for researchers to assess the effects of minimum wages.

Economists have developed a large body of research comparing the labor market outcomes in states that raise their minimum wage versus those that don’t. Yet a naive comparison of these two groups of states can lead to misleading conclusions because the variation of state-level minimum wage policies is not random (which is ideal for assessing the impact of government policies) and is instead geographically concentrated. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

My coauthors and I explain in our paper that the map divides states into two groups: states with high average minimum wages and states with low average minimum wages during the 1979-2014 period. States that have high minimum wages were more likely to have been raising their respective wage floors above the federal floor. States with low minimum wages typically followed federal policy. This difference is clearly region-specific.

This clustering of minimum wage policies within regions of the country is an obstacle for credible research on the minimum wage because comparing the employment of minimum wage-raising and non-raising states effectively compares regions such as the Northeast versus the South. Employment patterns differ in these regions because of a host of economic and political reasons not affected by the minimum wage. High minimum wage states, for example, also boast higher unionization rates and experienced smaller declines in unionization over the past three decades. They were much more likely to vote Democratic in the 2012 presidential election. In low minimum wage states, over the past 20 years, the foreign-born share of the population grew much faster.

In summary, there are reasons to be concerned that states that tend to raise their minimum wages have different employment trends than states that do not, irrespective of the minimum wage. Simply comparing minimum wage-raising and non-raising states can therefore give misleading estimates of the effects of the policy.

States where the minimum wage is high were experiencing employment problems even before minimum wages went into effect

Some minimum wage research does not adequately address the problems caused by the non-random pattern of minimum wage increases. In our paper my co-authors and I re-examine a key 2014 study, “More on Recent Evidence on the Effects of the Minimum Wage in the United States,” by David Neumark at the University of California-Irvine, Ian Salas at Johns Hopkins University, and William Wascher at the Federal Reserve Board. This study finds large, negative employment effects of the minimum wage on teenagers, a demographic group with a large share of minimum wage workers.

The methodology behind this study, however, also generates an implausible conclusion—that teen employment in high minimum wage states was falling in the years before the minimum wage was increased. The mistaken results of this study are a consequence of not controlling for the striking spatial pattern of minimum wage increases in different regions of the country.

One simple way to assess directly whether minimum wage-raising and non-raising states are comparable is to look at labor market outcomes before a minimum wage increase actually occurs. Borrowing from the language of randomized control trials in medicine, this can be thought of as a placebo or falsification test. We should not see the effects of drug before a drug is administered in a well-designed experiment. If we observe in a drug trial that the health of the treated group was improving relative to the control group even prior to taking the drug, then we should be hesitant to ascribe subsequent improvements in health to the causal effect of the drug itself.

Similarly, my co-authors and I examine the estimated effects of the minimum wage on teen employment in the years before and after minimum wage increases. We compare the results from the approach favored by Neumark, Salas, and Wascher to the approach we favor. First, we estimate the effects of the minimum wage using the preferred model of Neumark, Salas, and Wascher, in which any state is on average a good control for another state in the absence of minimum wage increases. Second, we consider the model that we prefer, one that controls for the non-random geographic pattern of minimum wage increases, allowing states to have different teen employment trends and restricting comparisons to nearby states.

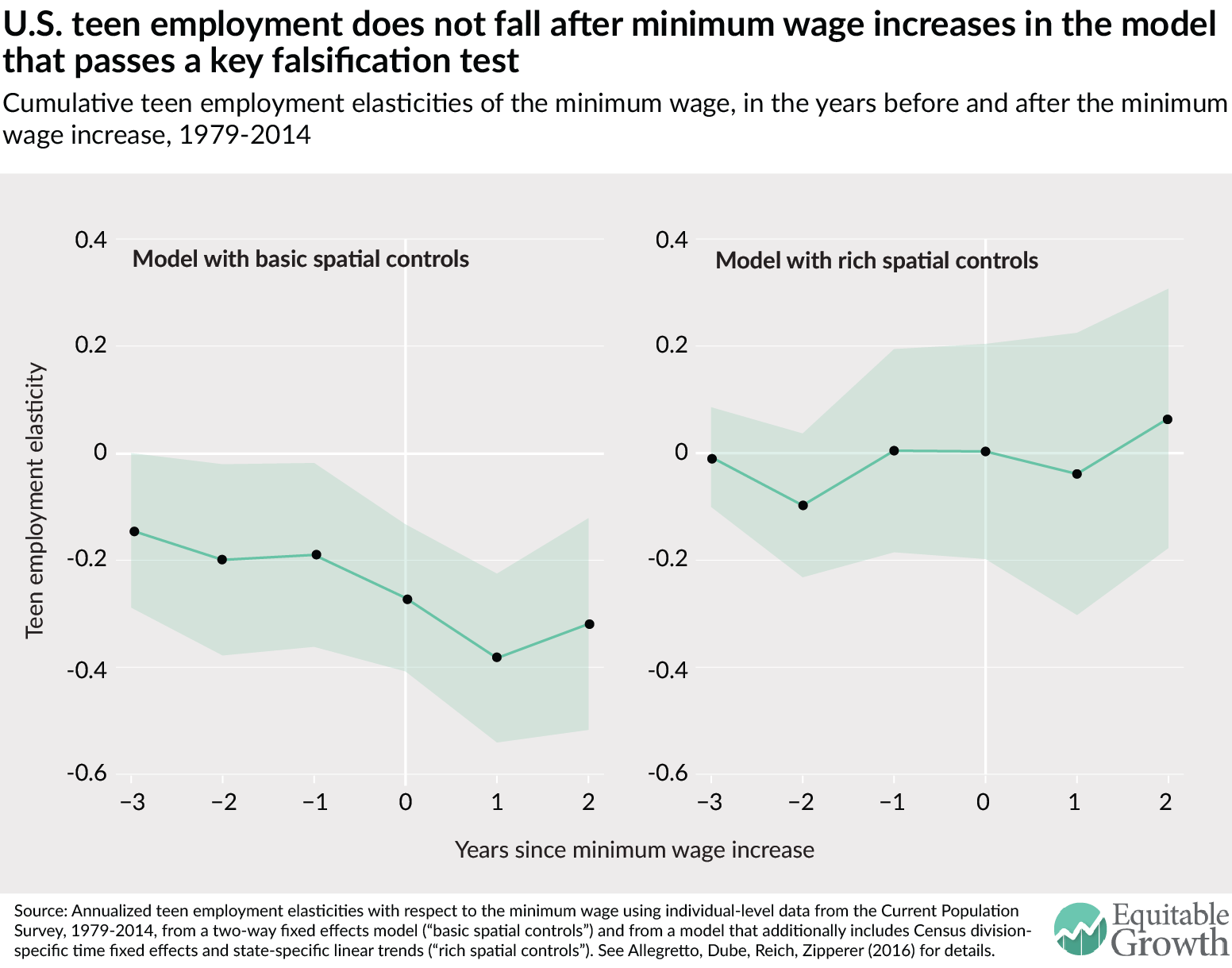

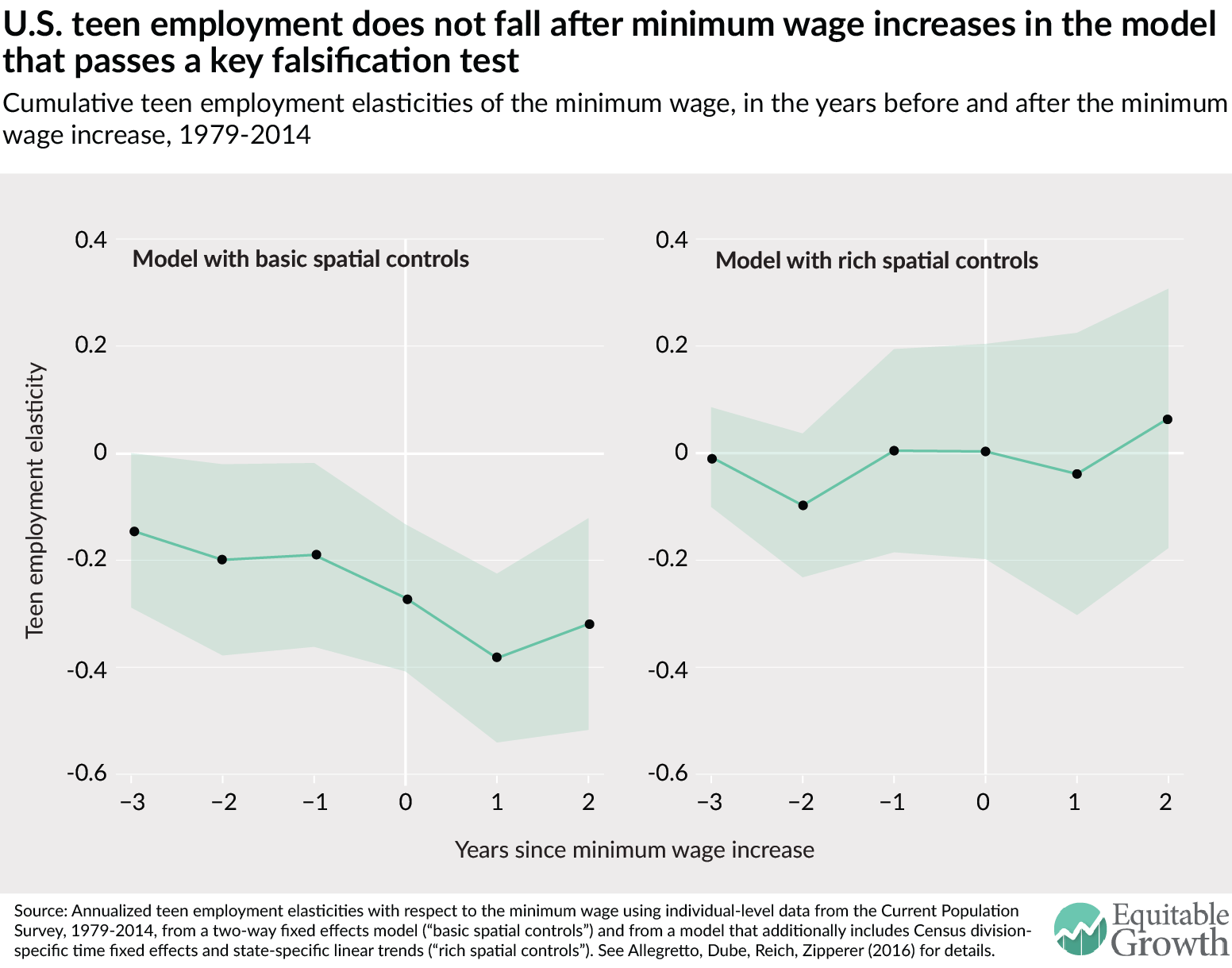

With these two models in hand, my co-authors and I calculate the elasticity of teen employment with respect to the minimum wage—specifically the percent change in teen employment in response to a 1 percent change in the minimum wage. Our findings show that the minimum wage did not lower teen employment in our preferred model (with rich spatial controls) which passes the falsification test. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

The model preferred by Neumark, Salas, and Wascher shows large, negative effects of the minimum wage at the time of the minimum wage increase and afterwards (years 0 through year 3, in the left panel of Figure 2). At the same time, the model decisively fails the falsification test. Teen employment in minimum wage-raising states is already low in all three years prior to the minimum wage increase (years -3 through -1). For every year prior to the minimum wage increase, their model produces a statistically significant negative employment effect—even though no minimum wage increase was enacted in those years.

This violation of the “parallel trends” assumption—that states on average have similar teen employment trends in the absence of minimum wage differences—is a clear sign not to trust the estimated employment effects of this model.

In contrast, my co-authors and I successfully control for the non-random pattern of minimum wage increases by using a model with a richer set of geographic controls (see the right panel of Figure 2). As is expected by a credible research design, there is not much change in teen employment in the years before the minimum wage increase. Teen employment elasticities during the pre-treatment period are generally small and are all statistically insignificant. In addition, there are no indications of negative employment effects in the years after the minimum wage increase. None of the point estimates are economically large or statistically significant by conventional standards.

Although these geographic controls are natural choices to account for the non-random spatial pattern of minimum wage increases presented in Figure 1, there are other research designs one could consider. In our paper, we present additional evidence from research designs that incorporate other controls for the non-random nature of minimum wage policies, such as limiting comparisons to nearby counties, or using estimators based on techniques that select alternative control groups. Many of these estimates also suggest small-to-no employment effects for teens.

As my coauthors and I explain, teenagers are a small share of the total workforce, but the studies of this group are nevertheless informative for understanding the overall employment effects of the minimum wage. If there were widespread employment losses due to the minimum wage, then we would likely see them among low-skilled groups such as teenagers. Yet the evidence we present in our paper suggests that teenagers did not suffer job losses for the kinds of minimum wage increases typically experienced in the United States over the past 35 years.

(Photo by Adam Croot, via Flickr)