“Equitable Growth in Conversation” is a recurring series where we talk with economists and other social scientists to help us better understand whether and how economic inequality affects economic growth and stability.

In this installment, Equitable Growth’s executive director and chief economist Heather Boushey talks with Stefano Scarpetta, the Director of Employment, Labour and Social Affairs at the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development in Paris, about how high levels of inequality are affecting economic growth in the organization’s 35 member countries and possible policy responses.

Read their conversation below

Heather Boushey: The OECD has been doing really interesting work over the past few years looking at how and whether inequality affects macroeconomic outcomes or outcomes more generally. A lot of questions are circling around the report that came out last year titled “In It Together: Why Less Inequality Benefits All.” One thing that really strikes me is that inequality isn’t a unitary phenomenon. It’s not just one thing. You can have inequality increasing at the top of the income spectrum, you can have something happening in the middle, you could have something happen in the bottom. But these are different trends and they may affect economic growth and stability in different ways because of their effects on people or on consumption or on what have you. That’s one of the things that I really enjoyed about that OECD report is that you used multiple measures of inequality; you didn’t just stick with one. So, I wondered if you could talk a little bit about that.

Stefano Scarpetta: Sure. Some indicators of income inequality, such as the Gini coefficient, of course don’t tell us exactly what’s happening with different income groups. So, much of the work we have done at the OECD is to look at the income performance of different groups along the distribution. And one of the findings that is emerging, not just in the United States but also across a wide range of advanced and emerging economies, is that income for those at the top 10 percent, and in many cases actually the top one percent, has been growing very rapidly. At the same time the income of those on the bottom—not only the bottom 10 percent but actually sometimes the bottom 40 percent—has been dragging, if not declining, in some countries.

This fairly widespread trend becomes very important when we think about policies to address inequalities, but also when you want to look at the links between inequality and economic growth. As you know, there are at least two broad strands of theory about the links between inequality and growth. A traditional theory focuses on economic incentives. Some inequality, especially in the upper part of the distribution, is needed to provide the right incentives for people to take risk, to invest, and innovate. An alternative theory instead focuses on missing opportunities associated with high inequality: it focuses more on the bottom part of the distribution, and stresses that high inequality might actually prevent those at the bottom of the distribution from investing in, say, human capital or health, thus hindering long-term growth..

We have done empirical work looking at the links between inequality and economic growth. This is very difficult, and though we have used some state-of-the-art economic techniques, we still have a number of limitations. We have looked at 30 years of data across a wide range of OECD countries. And basically, the bottom line of this analysis is that there seems to be clear evidence that when inequality basically affect the bottom 40 percent [of the income distribution], then this leads to lower economic growth. These results are fairly robust, but what’s the mechanism behind this effect? That’s what we’ve been doing as well.

Potentially there are different types of mechanisms. We have investigated one of them in particular: the reduced opportunities that people in the bottom part of income distribution have to invest in their human capital in high-unequal countries. The OECD has coordinated the Adult Skills Survey, which assesses the actual competencies of adults between the ages of 16 and 65 in 24 countries along three main foundation skills: literacy, numeracy and problem solving. Thus the survey goes beyond the qualification of individuals and allows us to link actual competencies with their labor market status. The survey actually measures what people can do over and above their qualifications. Then we looked at whether educational outcomes, not only in terms of qualifications but also actual competencies, are related to the socioeconomic backgrounds of the individuals themselves, and also whether the relationship between the socioeconomic backgrounds of individuals and the education outcomes vary depending on whether the individuals live in low- or high-inequality countries.

What emerges very clearly from the data—and these are micro data of a representative sample of 24 countries—is that there is always a significant difference or gap in the educational achievement of individuals, depending on their socioeconomic background. So individuals coming from low socioeconomic backgrounds tend to have worse outcomes whether we measure them in terms of qualifications, or even more importantly in terms of actual competencies — actual skills, if you like. The interesting result is that the gap tends to increase dramatically when we move from a low-inequality to a high-inequality country. The gap tends to be much, much bigger. The difference in the gap between those with intermediate or median socioeconomic backgrounds and those with high socioeconomic backgrounds is fairly stable across the income distribution level of inequality of these countries. But when we look at the highly unequal countries there is a drop, particularly among those coming from low socioeconomic backgrounds

One way to interpret this is that if you come from a low socioeconomic background, your chances of achieving a good level of education are lower. But if you are in a high-unequal country, the gap tends to be much, much larger compared to those coming from an intermediate or high socioeconomic background. And the reason is that in high-unequal countries it’s much more difficult for those in the bottom 10 percent —and indeed the bottom 40 percent— to invest enough in high-quality education and skills.

HB: That’s very consistent with research by [Stanford University economist] Raj Chetty and his coauthors in the United States on economic mobility, noting in U.S. parlance that the rungs of the ladder have become farther and farther apart. Would you say that these are consistent findings? One thing inequality does is it makes it harder to get to that next rung for folks at the bottom or even the mid-bottom of the ladder.

SS: Precisely, that’s exactly the point. The comparisons of the gap in educational achievements between individuals from different socio-economic backgrounds across the inequality spectrum suggest that the gap widens when you move from qualifications to actual competencies. So, basically, it’s not just a question of reaching a certain level of education, but actually the quality of the educational outcomes you get. In highly unequal countries, people have difficulty not only getting to a tertiary level of education, but also accessing the quality of the education they need, which shows very clearly in terms of what they can do in terms of literacy, numeracy and problem solving. So, yes, high inequality prevents the bottom 40 percent from investing enough in human capital, not only in terms of the number of years of education, but also in terms of acquiring the foundation skills because of the adverse selection into lower quality education institutions and training.

HB: I want to step back just for a moment. To summarize, it sounds like the research that you all have done finds that these measures of inequality are leaving behind people at the bottom and that affects growth. Is there anything in your findings that talked about those at the very top, the pulling apart of that top 1 percent or the very, very top 0.1 percent? What did your research show for those at the very top?

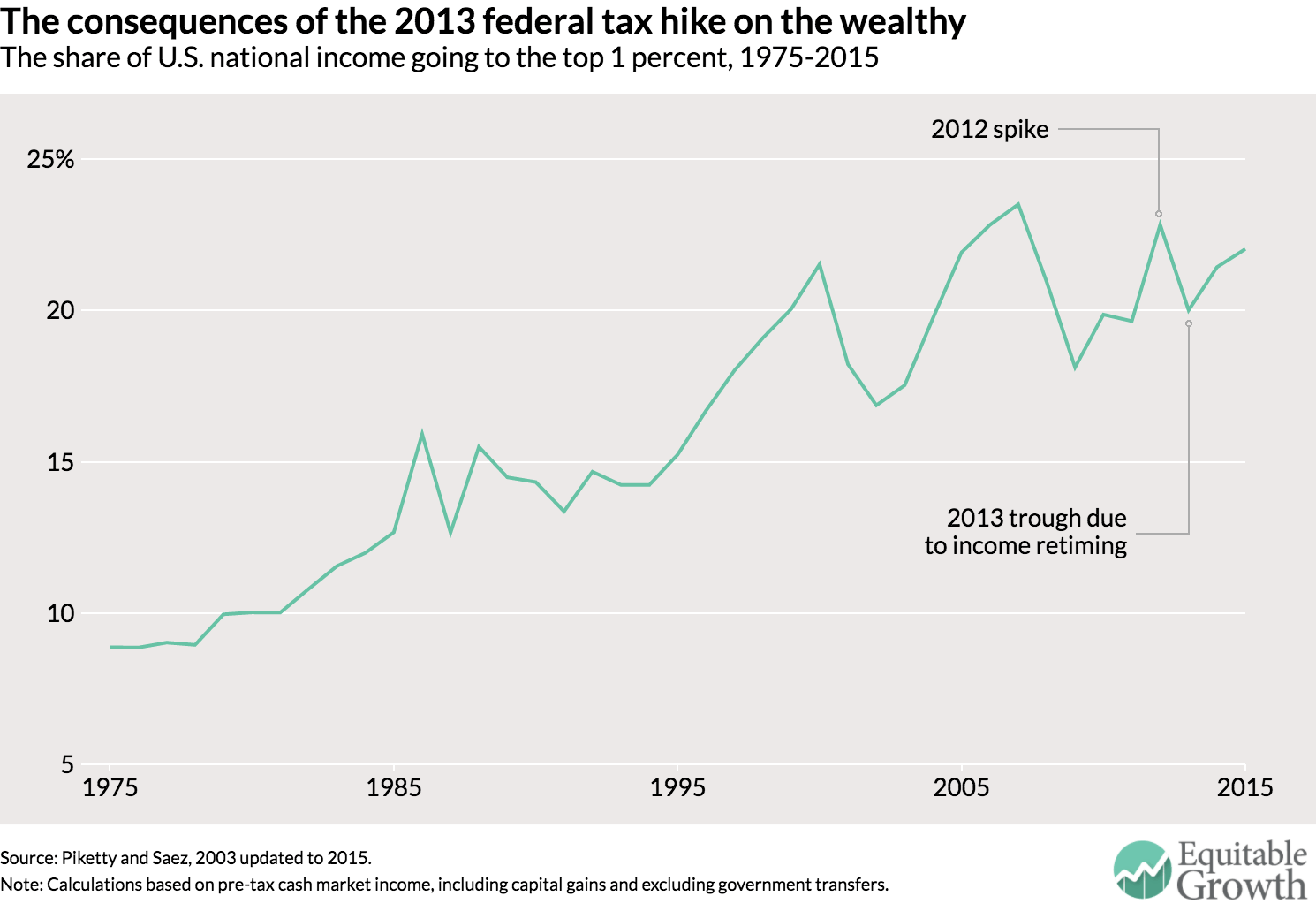

SS: It’s well known that the top one percent, actually the top 0.1 percent, are really having a much, much stronger rate of income growth than everybody else. This takes place in a wide range of countries, not to the same extent, but certainly it takes place.

The other descriptive finding we have is that for the first time in a fairly large range of OECD countries, we have comparable data on the distribution of wealth, not just the distribution of income. And what that shows is that there is much wider dispersion of the distribution of wealth, which actually feeds back into our discussion about investment in education because what matters is not just the level of income, but actually the wealth of different individuals and households.

Just to give you a few statistics: in the United States the top 10 percent has about 30 percent of all disposable income, but they’ve got 76 percent of the wealth. In the OECD, on average, you’re talking about going from 25 percent of income to 50 percent of wealth. So, basically, the distribution of wealth adds up to create a deep divide between those at the top and those at the bottom. The interesting thing is that there are differences in the cross-country distribution of income and wealth. Countries that are more unequal in terms of income are not necessarily more unequal in terms of distribution of wealth. The United States is certainly a country that combines both, but there are a number of European countries, such as Germany or the Netherlands, that tend to be fairly egalitarian in terms of distribution of income, but much less so when you look at distribution of wealth.

I think that going forward, research has to take the wealth dimension into account because a number of decisions made by individuals rely of course on the flows of income, but also in terms of the underlining stock of wealth that is available to them.

Going back to your question: the fact that the top 10 percent is growing much more rapidly does not necessarily have negative impact on economic growth. What really matters is the bottom 40 percent, which as I said before justifies our focus on opportunities and therefore on education. And the work we are doing now at the OECD extends our analysis to look at access to quality health services. My presumption is that individuals in the bottom 40 percent, especially in some countries, might be not as able as others to access quality health. And therefore, this also affects the link between health, productivity, labor market performance, and so on. This might also be an effect that becomes a drag on economic growth altogether.

HB: One really striking finding that really struck me in the OECD report, as an economist who focuses on policy issues, is that your analysis doesn’t conclude the policy solutions are really in the tax-and-transfer system. As you’ve already said, it’s really thinking about education, perhaps educational quality, health quality—things that might be a little bit harder to measure in terms of the effectiveness of government in some ways. After all, it’s easier to know exactly how much of a tax credit you’re giving someone versus the quality of a school or health outcome. You can certainly measure these outcomes, but it’s more challenging. It seems to me that a lot of the conclusions of this research are that it’s not enough to focus on taxes and transfers, but rather that we have to focus on these things that are harder, in the areas of education and health outcomes, focusing on people and people’s development. Would that be a fair assessment of the emphasis that this research is leading you to?

SS: To some extent, because I think both are important. Let me try to explain why. The first point is that more focus should indeed go into providing access to opportunities. And these are not just the standard indicators of how much countries spend on public and private education and health, but actually how people in different parts of the distribution have access to these services, and the quality of the services they receive. So I think the focus should be on promoting more equal access to opportunities, which means going beyond looking at access and quality of the services that individuals receive, especially those from the bottom 10 percent to the bottom 40 percent of the income distribution. This is much more difficult to measure, but I think we have to consider fundamental investment in human capital. And a lot of the policies should move toward providing more equal access to opportunities, at least in the key areas of education, health, and other key public services.

Now, the other point is that if you don’t address the inequality of outcomes then you can’t possibly address the inequality of opportunities. In countries in which the income distribution is so unequally distributed it’s difficult to think that individuals, despite public programs, can actually invest enough on their own to have access to the right opportunities. So, the two things are very much linked. By addressing some of the inequality in outcomes, you’re also able to promote better access to opportunity for individuals. So, I think it’s really working on both sides.

We are not the only ones who have been arguing for years that the redistribution effort of countries has diminished over time. It has diminished over the past three decades because of the decline in the progressivity of income taxes and because the transfer system in general has declined in terms of the overall level, even though some programs have become more targeted. But we’re not necessarily saying spend more in terms of redistribution, but spend well in terms of benefit programs. So I think the discussion becomes: Focus more on opportunities, address income inequality because this is a major factor in the lack of access to opportunities, but be very specific in what you do in terms of targeted transfer programs. In particular, focus on programs that have been evaluated and showed that they actually lead to good outcomes.

HB: I’d also like to talk about gender- and family-friendly policies. I noticed in the report that you talked a lot about the importance of reducing gender inequality on overall family inequality outcomes but also on the opportunity piece. Could you talk a little bit about the importance of these in terms of the research that you found?

SS: One of the most interesting results of our analysis in terms of the counteracting factors of the trend increase in income inequality across the wide range of OECD countries—including a number of the key emerging economies—has been the reduction in the gender gaps. The greater participation of women in the labor market has certainly helped to partially, but not totally, alleviate the trend increase in market income inequality. But as we know, there are gender gaps not only in labor market participation, but increasingly also in the quality of jobs that women have access to compared to men. Depending on the country, of course, there are large differences.

In that context, I’m very glad we have been supporting the Group of 20 Australian presidency in 2014, which brought a gender target into the forum of the G-20 leaders. Now, they have committed to reducing the gender gap in labor force participation by 25 percent by 2025. It’s only one step into the process, but I think it’s an important signal. We at the OECD also have the “Gender Recommendation,” a specific set of policy principles that all OECD countries have engaged in, with a fairly ambitious agenda on gender equality, focusing on education, labor markets, and also entrepreneurship.

Ensuring greater participation of women in the labor market remains a very important objective, but looking more into the quality of jobs that women have access to, and making sure that policy can facilitate women entering the labor market and also having a career is very important. And also allowing women to reconcile work responsibility with family responsibility. In that context, what we are doing perhaps more than in the past is looking not only at what women should be doing or have to do, but also at what men can do and should do. At the OECD, for example, we are looking specifically at paternity leave, because many of the decisions at the household level are taken jointly by the father and the mother. And I think while we have made some progress in changing the behavior of mothers, much remains to be done to also change the behavior of fathers.

We are looking at some of the interesting policies that a number of countries are implementing to promote paternity leave, for example by reserving part of the parental leave only to the father. Either the father takes the leave or it is not given to the household. And there are a number of interesting results. Some countries, such as Germany, have reserved part of the parental leave going to the father and have been able to increase the number of fathers who take parental leave by a significant proportion. Again, the focus should certainly be on all the different dimensions of inequality, including gender inequality, in the labor market, but also look at the interactions of individual behaviors of men and women and those of the companies in which they work. We are doing interesting research in the case of two countries that have very generous paternity leave, Japan and South Korea: 52 weeks. Yet, only 3 percent of the fathers take paternity leave. For male workers in these countries, absence from work because of family reasons is perceived to be a lack of commitment to the firm and employer and thus may have a negative impact on their careers; not surprisingly only a few men actually take paternity leave.

HB: One thing I know from my own research is that United States, of course, is different in that we tie in the states that have family leave, such as California, New Jersey, and Rhode Island, with New York soon implementing it, to our federal unpaid family and medical leave, which is 12 weeks of unpaid leave and which covers about 60 percent of the labor force. At both the state and federal level, the leave is tied to the worker. So, we already have a “use it or lose it” policy in place. So for children who are born to parents California, both the mother and the father have an equal amount of leave, but if dad doesn’t take it then the family doesn’t get it.

We’ve seen from research that once the leave was paid; men are increasingly taking it up. If the OECD hasn’t been looking at this in a cross-national comparative way, it might be an interesting case study or research project that I’ll just put out there in terms of how the United States has done. That’s the only thing that we’ve done right on paid leave vis-a-vis other OECD countries.

My last question here. Going back to the beginning of our conversation, the OECD research found that the rise of inequality between 1985 and 2005 in 19 countries knocked 4.7 percentage points off of cumulative economic growth between 1990 and 2010. That’s a big deal. The policy issues that we’ve been talking about are wide-ranging and possibly expensive, but also very important, it seems, for economic growth.

From where you sit in Paris at the OECD, are you seeing policymakers both at the OECD but also in member countries that you work with, really taking this research seriously? And are there any big questions that you think an organization like the Washington Center for Equitable Growth should be asking in our research to help show people what the evidence says? Are there sort of big questions that policymakers say, “Oh, I’ve seen this report, Stefano, but I don’t believe this piece of it.” Are there any avenues that you think we need to pursue where people are perhaps a little bit more skeptical if they’re not taking it as seriously as this research implies?

SS: These are all extremely relevant and very good questions, Heather. Let me start with the first point you raised; over a 30-year period, and across a wide range of OECD countries, high and increasing inequality has knocked down economic growth. Obviously this is not the last word and further research is needed. As we discussed, the identification of the effect and the links are not straightforward. We have used what we think is the best state-of-the-art economic techniques, but of course it’s not the last word. It would certainly help to work along these lines with a number of researchers to gather more evidence.

But it also is important for researchers to look at the channels through which increasing high levels of inequality might be detrimental for growth: namely by under-investment in broadly-defined human capital of the bottom 40 percent and therefore long-term economic growth. I think this is certainly an area in which there is a lot of scope for doing more work. In particular, there’s a lot of space for doing serious micro-based analysis looking at the extent to which individuals with low socioeconomic backgrounds actually have difficulties investing in quality education, quality human capital, and other areas.

Now, in terms of the work we have done— and the work that was done also by the International Monetary Fund and others— I think we are contributing somewhat to changing the narrative about inequality. For decades, there was a field of research on the economics of inequality, but this was largely confined to addressing inequality for social cohesion —for social reasons. We hope that now we have brought the issue of growing inequality toward the center of policymaking because inequality might be detrimental to economic growth, per se. So, even if you just want to pursue economic growth, you might want to be careful about increasing income inequality in your country.

We are not there yet, but I think there are a number of signals that indicate growing dissatisfaction in many countries, at least in part be driven by the fact that people don’t see the benefits [of economic growth] even amid a recovery. One of the more clear signals is that now the issue of inequality is discussed more openly in our meetings with colleagues from the fianance and economy ministries. In fact, the broad economic framework we’re now using at the OECD is inclusive growth. I would say that these are not things that would have been possible a decade ago. There is now a fairly consistent narrative around the need to pursue inclusive growth. And there is a strong focus on employment and social protection, and on investments in human capital.

I think the research community really needs to feed this discourse. There might be still some temptation as soon as economic growth resumes to revert back to traditional economic growth focus. And because there are a lot of fears and concerns about secular stagnation, the thinking could focus on growth because we need growth back, and we will deal with the distribution of the benefits of growth at a later stage. But, we should really have a comprehensive strategy that fosters a process of economic growth that is sustainable and deals with some of the underlining drivers of inequality.

HB: Thank you. And I will note our very first interview for this series “Equitable Growth in Conversation” was with Larry Summers, who actually talked about the importance of attending to inequality if we want to address secular stagnation.

SS: Exactly.

HB: This has been so enormously helpful and so interesting. We here at Equitable Growth really appreciate the work that you all are doing at the OECD and find it incredibly illuminating. Thank you so much for taking the time to talk to us today.

SS: Thank you, Heather. Thank you very much. It’s been a pleasure.