The rise of the female workforce alongside women’s increased education in high-income nations marks one of the most stunning economic transformations in recent history. Over the past 40 years, many of these countries have responded by implementing a host of family policies that make it easier for women to balance work and family life. But how effective have these policies been in narrowing the gender gap in wages and employment?

The rise of the female workforce alongside women’s increased education in high-income nations marks one of the most stunning economic transformations in recent history. Over the past 40 years, many of these countries have responded by implementing a host of family policies that make it easier for women to balance work and family life. But how effective have these policies been in narrowing the gender gap in wages and employment?

A new working paper by Claudia Olivetti of Boston College and Barbara Petrongolo of the London School of Economics examines family policy across Western, high-income European countries, the United States, and Canada to try and establish whether there is a cause-and-effect relationship between family polices, such as paid parental leave after the birth of a child and increased spending on childcare and early learning programs, and women’s employment outcomes.

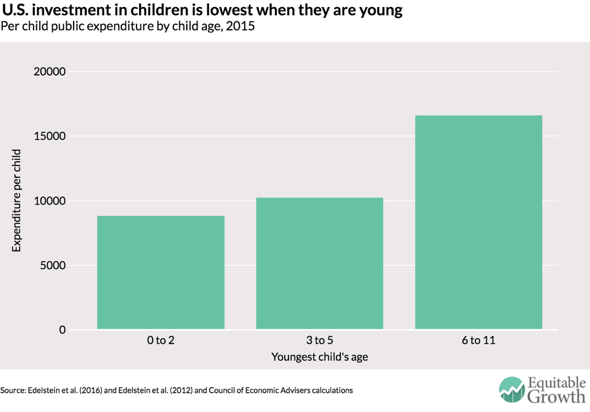

Olivetti and Petrongolo show that spending on childcare and early childhood learning, whether through subsidized childcare or in-work benefits (such as the Earned Income Tax Credit in the United States), has a negative correlation with the employment gap between men and women and an even larger effect on the gender wage gap. They find that “by this same logic, this implies that wage gaps are predicted to shrink with childhood spending.” This research should be considered in light of the fact that in 2012, the United States ranked 33rd out of 36 nations in the terms of investing in early childhood care and education relative to their overall income, according to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development.

The authors also look at how maternity leave policies affect women’s outcomes. Though the median combined paid and unpaid parental leave was 60 weeks for the countries in the analysis, Olivetti and Petrongolo find that maternity leave has a small, but positive, effect on women’s employment and earnings for up to 50 weeks. Leave that goes beyond 50 weeks can have a negative effect on women’s earnings and career trajectories. Considering that U.S. policymakers are considering a bill that would provide families with only 12 weeks paid leave, that means American women would see a benefit according to the author’s results.

Olivetti and Petrongolo note that once the results are broken down by education level, there is a much larger benefit for low-skilled workers, while paid leave may even be “detrimental” for college-educated women. This may be because many high-skilled jobs tend to require more face time and longer hours. Taking more than a year out of the workforce to care for a new child, as many women in some European countries do, could signal a lack of commitment in certain environments, and women may be “mommy tracked” or pushed out altogether.

It’s also important to consider that the study encompasses a time when paid leave policies were usually confined to women. The authors do admit that while many countries have begun implementing leave for fathers, albeit on a more modest scale compared to what is allotted for women, the recent time frame makes it hard to evaluate. Research shows, however, that policies that are limited to or only used by women can backfire, which may explain why the Olivetti and Petrongolo’s results are so modest.

The reason? Maternity leave policies, if not accompanied by leave for men, can lead to discrimination against young women and also lock-in gender norms within heterosexual couples trying to balance their work and home life. A carefully-designed, gender-neutral paid leave policy, however, can socialize men to help more at home and create a “large and persistent” impact on gender dynamics even years after the leave period has ended.

The extent to which the United States is an outlier in the adoption of family friendly work-life policies is remarkable. While U.S. women have caught up to men in terms of educational attainment and show high levels of labor force participation in their 20s, that number begins to drop off once they reach their 30s and 40s because of childcare responsibilities. That’s because, despite being wealthier than many of the countries in this study, the United States, as mentioned earlier, is the only country without any kind of paid leave policy and spends very little on young children, meaning that parents must pick up the slack. Many women do so by cutting back at work or dropping out altogether, to the detriment of their long-term financial security and the potential future growth of our national economy.

The rise of the female workforce alongside women’s increased education in high-income nations marks one of the most stunning economic transformations in recent history. Over the past 40 years, many of these countries have responded by implementing a host of family policies that make it easier for women to balance work and family life. But how effective have these policies been in narrowing the gender gap in wages and employment?

The rise of the female workforce alongside women’s increased education in high-income nations marks one of the most stunning economic transformations in recent history. Over the past 40 years, many of these countries have responded by implementing a host of family policies that make it easier for women to balance work and family life. But how effective have these policies been in narrowing the gender gap in wages and employment?