Current conversations among academics and policymakers about corporate tax reform in the United States largely focus on the controversial border adjustment tax, projected revenue losses, and the distributional impacts of proposed federal tax reforms now under discussion in Washington, D.C. While it is critical to unpack these tax reform ideas, there’s another important ingredient to consider: pass-through businesses.

Pass-through businesses—such as S Corporations, Limited Liability Companies, Sole Proprietorships, and Partnerships—are firms whose income is not subject to the typical corporate income tax. Instead, their profits are “passed-through” to the owners of businesses and taxed on their individual income tax returns. Currently, this means that pass-through business income can be taxed up to the top individual marginal tax rate of 39.6 percent.

By organizing as a pass-through business as opposed to a traditional C Corporation, owners can gain a tax advantage, which can happen in two ways. First, they will face a lower rate if their personal income tax rate is lower than the corporate rate. But even if the personal rate isn’t lower, their ownership stake won’t face the capital gains tax in addition to corporate tax, which again gives them an advantage.

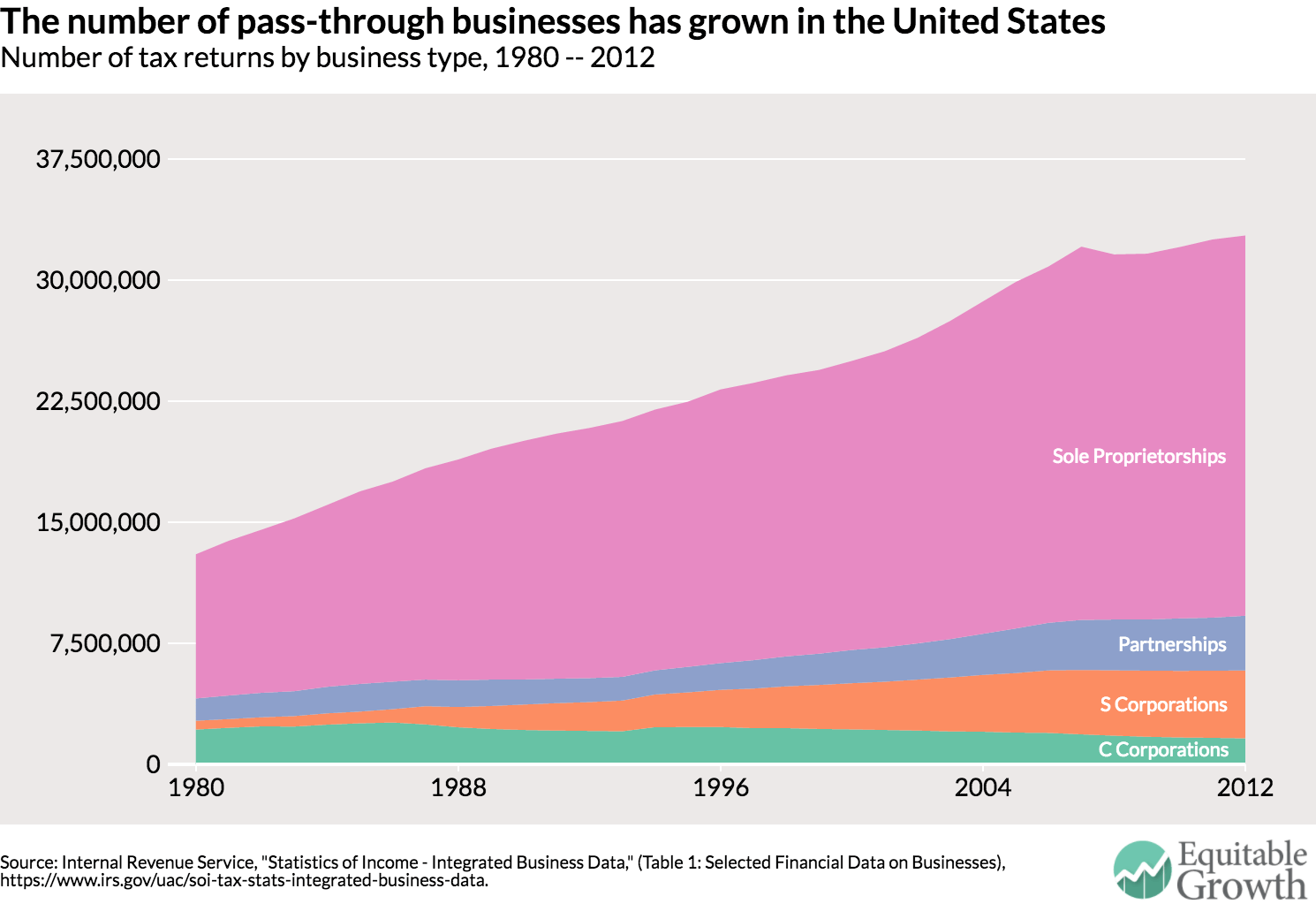

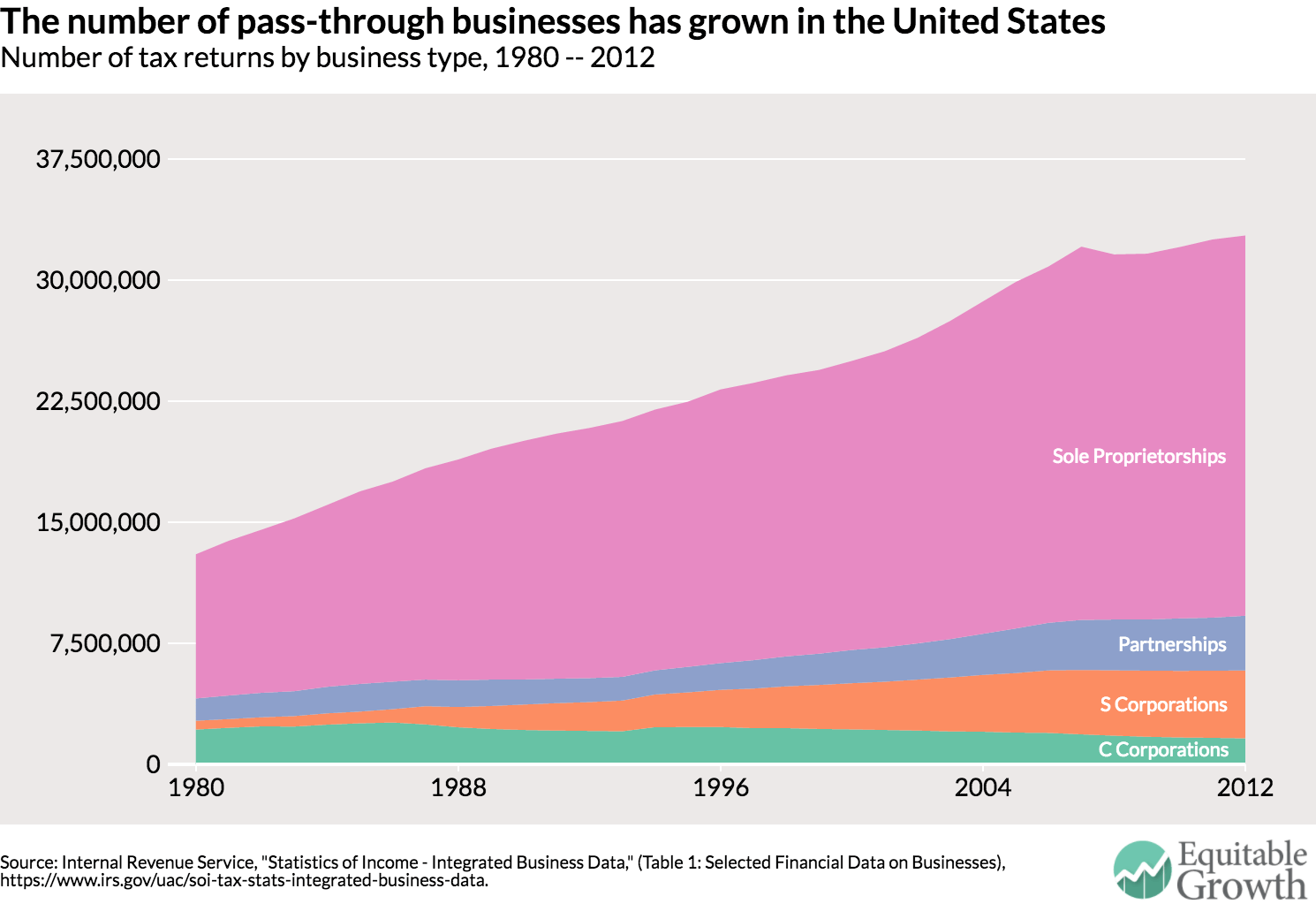

These advantages are important given that the number of pass-through firms has grown tremendously since the 1980s. (See Figure 1.) Over this same period, according to research that uses tax data from the U.S. Treasury Department, the business income accruing to pass-through businesses has also grown. In 1980, 21 percent of business income went to pass-through businesses, but by 2011, pass-throughs earned 54 percent of business income.

Figure 1

Pass-through firms clearly play a central role in the U.S. business milieu. But even still, there is significant ambiguity and disagreement about how Congress and the new Trump administration will handle any reforms to this part of the U.S. tax code. On one hand, Speaker of the House Paul Ryan (R-WI) has unveiled a plan that would cap the pass-through tax rate at 25 percent—though the top tax rate for individuals would be reduced to 30 percent. On the other hand, President Donald Trump’s tax agenda reduces the individual income tax rate to 33 percent and sets the corporate tax rate and the pass-through business tax rate at 15 percent.

As the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities and the Tax Policy Center both note, the gap between the top pass-through business rate and the top individual tax rate would, in all likelihood, encourage tax avoidance. In an example, Chuck Marr, Chye-Ching Huang, Brandon Debot, and Guillermo Herrera of the CBPP explain that business executives—a law firm partner for instance—could recategorize their high salaries as business income to exploit the lower pass-through tax rate, resulting in a large tax cut. To make matters worse, these changes to pass-through taxation would ultimately benefit only people at the very top of the U.S. income ladder. In the same study that used data from the Treasury Department, the researchers found that 69 percent of pass-through business income goes to the top 1 percent, dispelling the idea that middle-class small-business owners are the target population.

While there is still uncertainty about the fate of pass-through business taxation—and even corporate tax reform writ large in Congress this year—the growing concerns about both the Ryan and Trump plans’ inequitable effects can’t be ignored. To begin to address these issues, economist Kim Clausing of Reed College instead suggests harmonizing the taxation of different types of businesses. Specifically, she argues that the size of a business could be another requirement for garnering pass-through status. The Center for American Progress also put forward the idea of implementing mechanisms such as an entity-level tax for large pass-through businesses. Regardless of what the solution to the pass-through loophole may look like, it must help assure the economic health of the U.S. economy and Americans up and down the income ladder.