This is a weekly post we publish on Fridays with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth published this week and the second is the work we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

The rise in U.S. income inequality is well known by now. But what is far less well known is that those gains at the top are accruing disproportionately to a few race groups. Jessica Fulton writes about new research on income mobility and inequality between and within racial and ethnic groups in the United States.

The latest release in the Equitable Growth Working Paper series features new research from University of California, Berkeley economist Danny Yagan. His work looks at how the strength of the Great Recession led to such a weak recovery in U.S. employment rates.

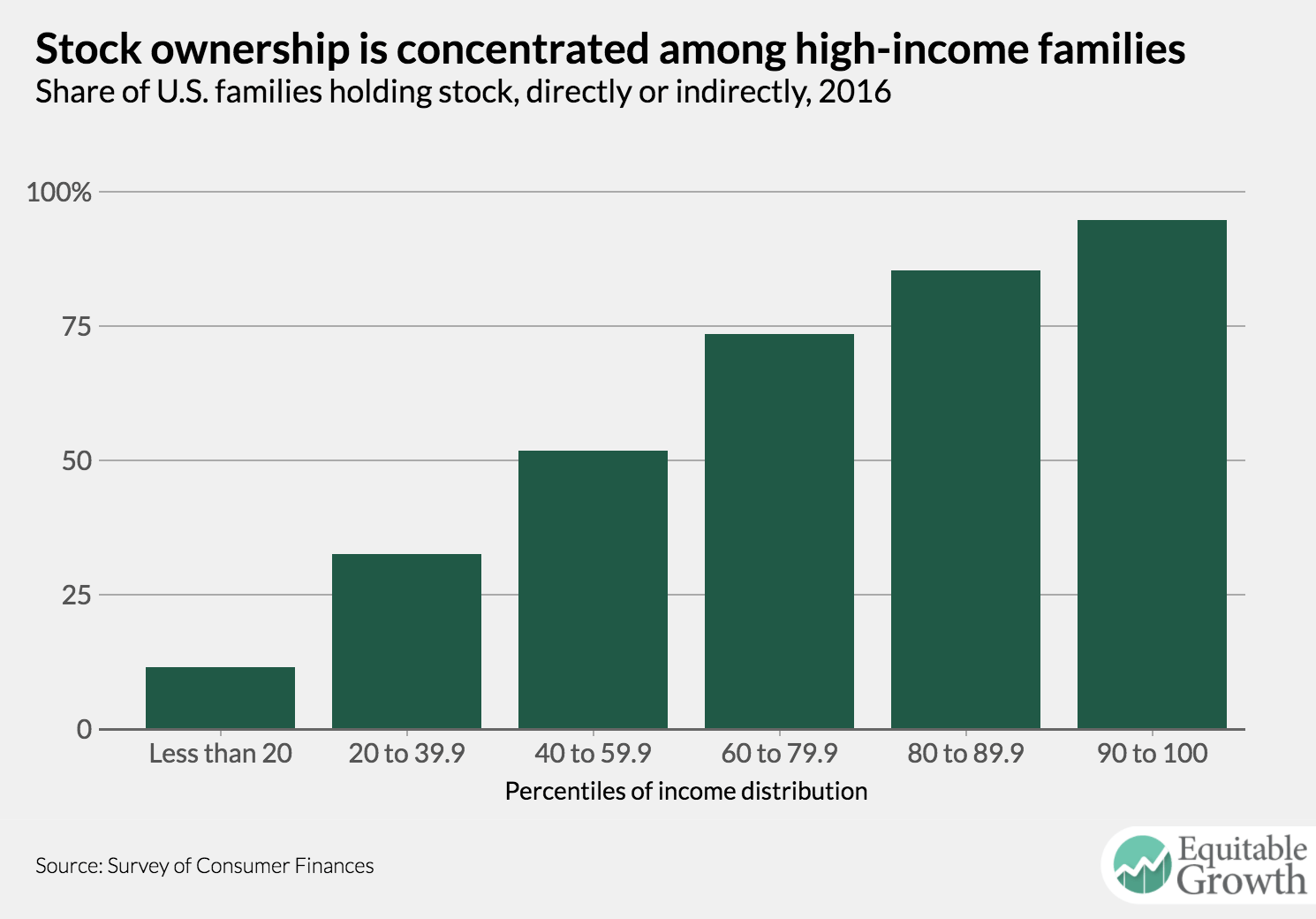

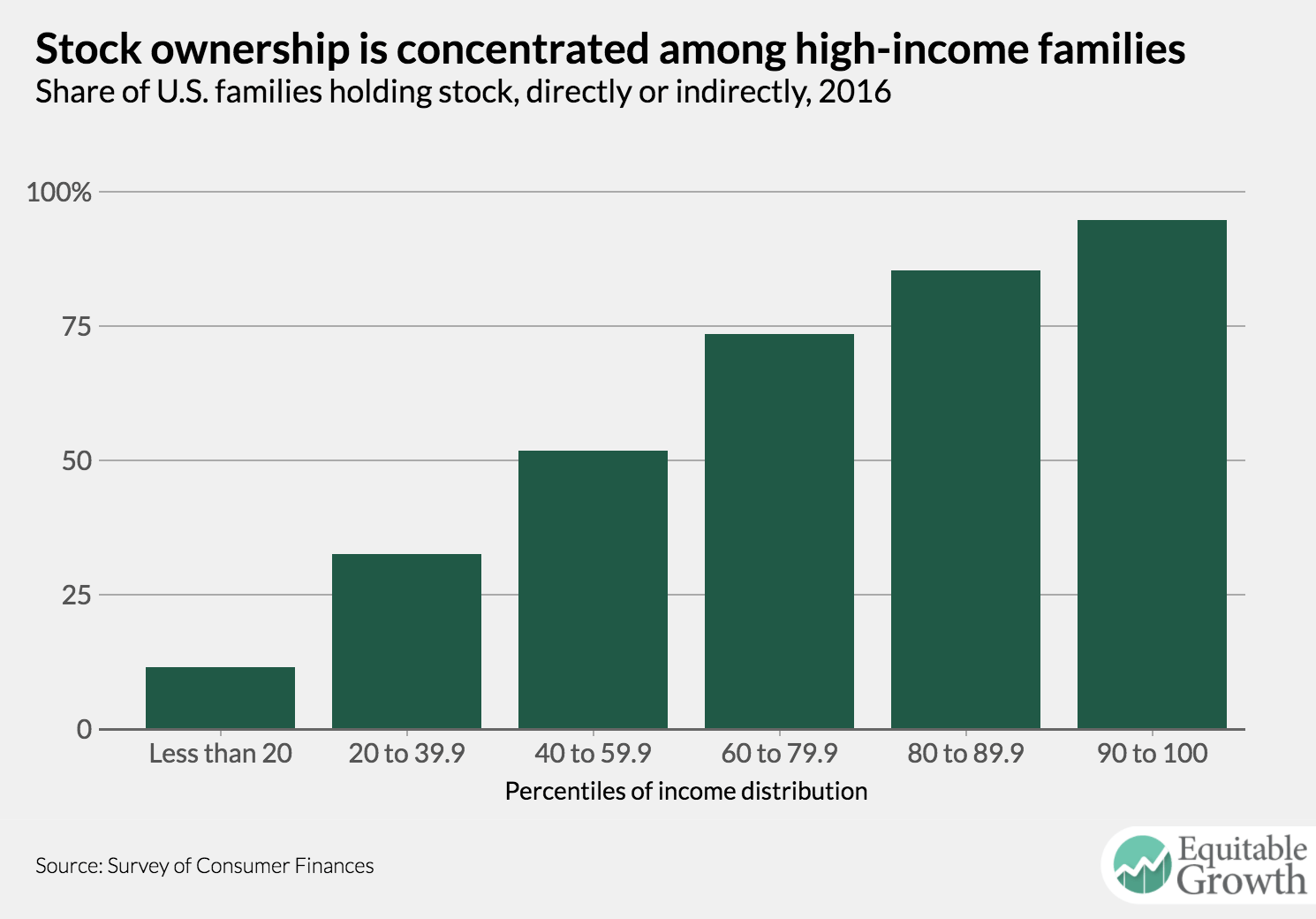

The Federal Reserve releases new data on the U.S. distribution of wealth every three years and the 2016 edition of the Survey of Consumer Finances was released this Wednesday. Here are four charts on the current state of wealth inequality.

In the latest installment of Equitable Growth In Conversation, Elisabeth Jacobs talks to Joan Williams about her recent book on the white working class.

Links from around the web

Job-hopping, a key way for workers to earn a raise, has been on the decline in recent years. There are many reasons for this decline, but Rachel Abrams highlights new research on a nefarious cause: employers conspiring to not poach employees. [nyt]

Why has nominal wage growth in advanced economies been so slow in recent years? Staffers at the International Monetary Fund took a look at the sources of weak wage growth and finds a combination of remaing slack in the labor market and slow productivity growth are to blame. [imf]

New ideas are getting harder to find. New research shows that the rising cost of creating innovation poses a supply-side constraint for innovation. Ryan Avent argues, however, that the demand for innovation shouldn’t be forgotten in an effort to create new ideas. [the economist]

The Federal Reserve has an official inflation target of 2 percent a year, but not many people are aware of that policy. Carola Binder, writing about her research, describes what happens to people’s expectations of inflation when they heard about this target. [quantitative ease]

Business dynamism and start-up activity are declining in the United States. Perhaps another country could serve as a role model. Alana Semuels argues that Sweden might be a good nation to look toward. [the atlantic]

Friday figure

Figure from “An update on the state of wealth inequality in the United States” by Nick Bunker