Today was the second day of the three-day annual meeting of the Allied Social Science Associations. The conference, held in Philadelphia this year, features hundreds of sessions covering a wide variety of economics research. Interesting research is all over the place here, so below are some of the papers that caught the attention of Equitable Growth staffers during the first day. Check out yesterday’s highlights and come back tomorrow evening for even more.

“Housing Wealth Effects: The Long View”

Emi Nakamura, Jon Steinsson, Alisdair McKay, and Adam Guren

Abstract: We provide new, time-varying estimates of the housing wealth effect back to the 1980s. We exploit systematic differential city-level exposure to regional house price cycles to construct our estimates. Our main findings are that: 1) Large housing wealth effects are not new: we estimate large effects back to the 1980s; 2) There is no evidence that housing wealth effects were particularly large in the 2000s; if anything, they are larger prior to 2000; and 3) We find no evidence of a boom-bust asymmetry that might arise from households hitting their borrowing constraints. We compare these findings with the implications of a “new canonical model” of housing wealth effects. This model yields large housing wealth effects. It can also explain why housing wealth effects have not risen over time despite the “great leveraging” of households since the 1980s and, in particular, the sharp increase in leverage associated with the 2006-2009 housing bust.

“Leave-taking and Labor Market Attachment Under California’s Paid Family Leave Program: New Evidence From Administrative Data”

Maya Rossin-Slater, Sarah Bana, and Kelly Bedard

Abstract: More than half of American mothers and over 90 percent of American fathers of infants under the age of one are employed in the labor market. Yet the United States remains the only OECD country without a national paid family leave (PFL) policy, and only 12 percent of private sector workers have access to PFL through their employers. In July 2004, California enacted the first state-level PFL policy that provides six weeks of leave with 55 percent of usual pay replaced (currently up to a maximum weekly benefit of $1,137); since then, three other states (New Jersey, Rhode Island, and New York) have followed suit. We use detailed administrative data from the California Employment Development Department on nearly 2 million PFL claims over 2005-2014 linked to individual-level quarterly earnings data to provide novel insights about California’s first-in-the-nation experience with PFL.

Our analysis delivers four key take-aways. First, we can precisely document trends in CAPFL take-up separately for bonding with a new child (hereafter, “bonding”) and caring for an ill family member (hereafter, “caring”). Our calculations suggest that about 40 percent (4.5 percent) of employed new mothers (fathers) made a bonding claim in 2005, while 47 percent (12 percent) of employed new mothers (fathers) made a bonding claim in 2014. Second, we find that low earning men and women are less likely to take leave than their more advantaged counterparts, consistent with survey reports that too little pay serves as a barrier for taking leave (Fass, 2009) and with polls suggesting that awareness of the program is lowest among low-income voters (DiCamillo and Field, 2015). We also show that individuals in firms with fewer than 50 employees—who are not concurrently eligible for unpaid job protected leave with health insurance through the Family and Medical Leave Act—are substantially under-represented in the PFL claims data, which may reflect their reluctancy.

“Occupational Licensing Reduces Racial and Gender Wage Gaps: Evidence From the Survey of Income and Program Participation”

Peter Q. Blair and Bobby Chung

Abstract: In order to work legally, 29% of U.S. workers require an occupational license. We show that occupational licensing reduces the racial wage gap between white and black men by 35%, and the gender wage gap between women and white men by 42%. For black men, a license is a positive indicator of non-felony status that aids in firm screening of workers, whereas women experience differentially higher returns to the human capital that is bundled with occupational licenses. The information and human capital content of licenses enable firms to rely less on race and gender as predictors of worker productivity.

“Sources of Displaced Workers’ Long-term Earnings Losses”

Marta Lachowska, Alexandre Mas, and Stephen A. Woodbury

Abstract: We estimate the earnings losses of a cohort of workers displaced during the Great Recession and decompose those long-term losses into components attributable to fewer work hours and to reduced hourly wage rates. We also examine the extent to which the reduced earnings, work hours, and wages of these displaced workers can be attributed to factors specific to pre- and postdisplacement employers; that is, to employer-specific fixed effects. The analysis is based on employer-employee linked panel data from Washington State assembled from 2002–2014 administrative wage and unemployment insurance (UI) records.

Three main findings emerge from the empirical work. First, five years after job loss, the earnings of these displaced workers were 16 percent less than those of comparison groups of nondisplaced workers. Second, earnings losses within a year of displacement can be explained almost entirely by lost work hours; however, five years after displacement, the relative earnings deficit of displaced workers can be attributed roughly 40 percent to reduced hourly wages and 60 percent to reduced work hours. Third, for the average displaced worker, lost employer-specific premiums account for about 11 percent of long-term earnings losses and nearly 25 percent of lower long-term hourly wages. For workers displaced from employers paying top-quintile earnings premiums (about 60 percent of the displaced workers in the sample), lost employer specific premiums account for more than half of long-term earnings losses and 83 percent of lower long-term hourly wages.

“Missing Women and African Americans, Innovation, and Economic Growth”

Lisa Cook and Yanyan Yang

Abstract: The process of converting invention to innovation is fundamental to economic growth but remains poorly understood. This paper uses data from the Survey of Doctoral Recipients to examine the determinants of patent and commercialization activity among PhD-holders and, more importantly, for the first time, those who commercialize their inventions over time. Recent studies have shown that rates of patenting and commercialization of ideas by women and African Americans have lagged those of U.S. inventors. What accounts for these differences in patenting and commercialization? Consistent with earlier research, we find that African Americans and women apply for patents 54 and 55 percent less than men, patent 54 and 60 percent less than men, and commercialize their patents 55 and 60 percent than men. We find that those who commercialize their patents over time are productive in research, are at large firms, are in the physical sciences and engineering, and are largely neither women nor African Americans. Given the important progression from basic research to invention to commercialization of ideas to higher living standards, we estimate that GDP per capita could rise by 0.88 percent to 4.6 percent with the inclusion of more women and African Americans in the initial stages of the process of innovation.

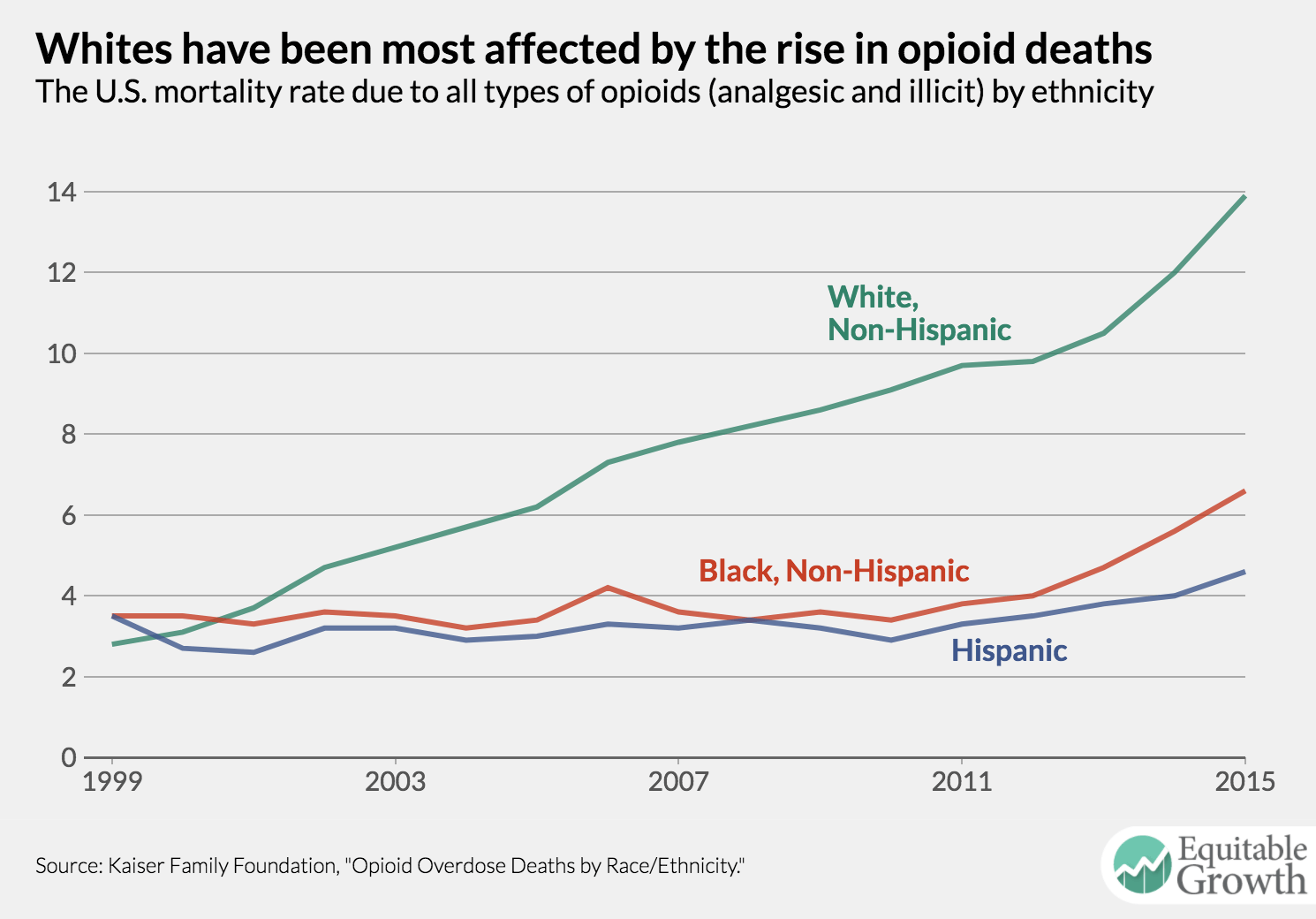

“Road to Despair and the Geography of the America Left Behind”

Mark Partridge and Alexandra Tsvetkova

Abstract: The United States has always experienced spatial differentials in economic activity and wellbeing. Yet, a long-running force that mitigated these disparities was economic convergence. However, beginning in the 1980s, such convergence forces weakened and economic activity and well-being began to widely diverge. In particular, in the wake of the Great Recession, this divergence is increasingly leading to large regions that appear to be left behind. This study will assess economic conditions in the 21th century by splitting the time periods before and after the Great Recession in appraising the causes for the post-recession decline in economic activity in these “forgotten” places. The analysis will occur over the 2001-2016 period using metropolitan and nonmetropolitan county-level data. We ask whether these distressed places are simply suffering from continued deindustrialization hitting manufacturing and (coal) mining-dependent locations, or is it more related to the occupational mix, human capital, and lack of entrepreneurial conditions that mean that struggling communities lack the basic foundation and resilience to adjust to adverse economic shocks? Likewise, some of these disadvantages may relate to long-term issues related to remoteness and the lack of agglomeration economies that will be extremely difficult to address through public policy. The economic outcomes that will be examined will focus on job growth, but there will also be some assessment of health outcomes, poverty rates, inequality, median household income, and average wages to further address issues of well-being.

“Making Financial Globalization More Inclusive”

Jonathan D. Ostry, Davide Furceri, and Prakash Loungani

Abstract: The distributional effects of financial globalization, unlike those of trade, have gone largely unrecognized. In fact, however, episodes of capital account liberalization are followed by an increase in the Gini coefficient and top income shares and declines in the labor share of income. These distributional effects hold with a de jure measure of liberalization and only get stronger when this measure is scaled by the extent of the capital flows that ensue in the aftermath of liberalization. Financial globalization emerges as a robust determinant of inequality, even after accounting for the effects of trade, technology and other drivers. At the same time, the output effects of financial globalization remain elusive and appear to be restricted to cases where financial depth and inclusion are high and where liberalization is not followed by a crisis. Financial globalization thus poses very difficult equity-efficiency tradeoffs and making it more inclusive requires, as a start, recognition of this fact.