July Jobs report: Job growth ramps up, but the construction sector struggles

The recovery in the labor market continued to pick-up steam as the U.S. economy added 943,000 jobs last month, according to the most recent Employment Situation Summary released today by the U.S. Department of Labor’s Bureau of Labor Statistics. The unemployment rate fell from 5.9 percent in June to 5.4 percent in July and the share of the U.S. population ages 25 to 54 with a job—a measure known as the prime-age employment-to-population ratio—climbed from 77.2 percent to 77.8 percent.

These indicators reflect that last month was a very strong one for the U.S. economy, yet the labor market has not fully recovered and millions of workers continue to experience the economic pain brought about by the coronavirus pandemic. The prime-age employment-to-population ratio, for instance, continues to be 2.6 percentage points below its February 2020 level. While the labor force participation rate rose slightly with respect to the previous month, at 61.7 percent it is at the same level it was in August 2020.

This most recent U.S. labor market data show that across race and ethnicity the unemployment rate for Black workers fell 1 percentage point between mid-June and mid-July, although at 8.2 percent, it continues to be higher than for any other major racial or ethnic group and the labor force participation rate of Black workers declined in July. The jobless rate for Latinx workers is at 6.6 percent, for Asian American workers at 5.3 percent, and for White workers at 5.2 percent.

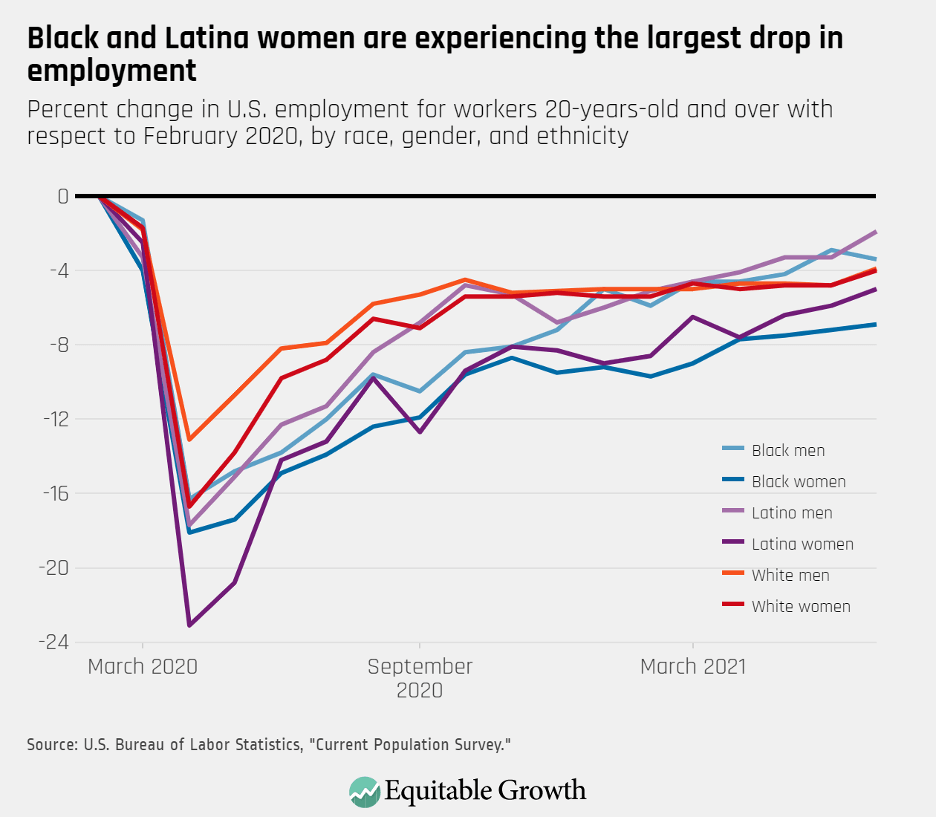

By race, ethnicity, and gender, the latest data show that among workers 20 years of age or older, employment continues to be down the most for women of color. In July 700,000 fewer Black women and 594,000 fewer Latina women had a job than in February 2020—a decline of 6.9 percent and 5 percent, respectively. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

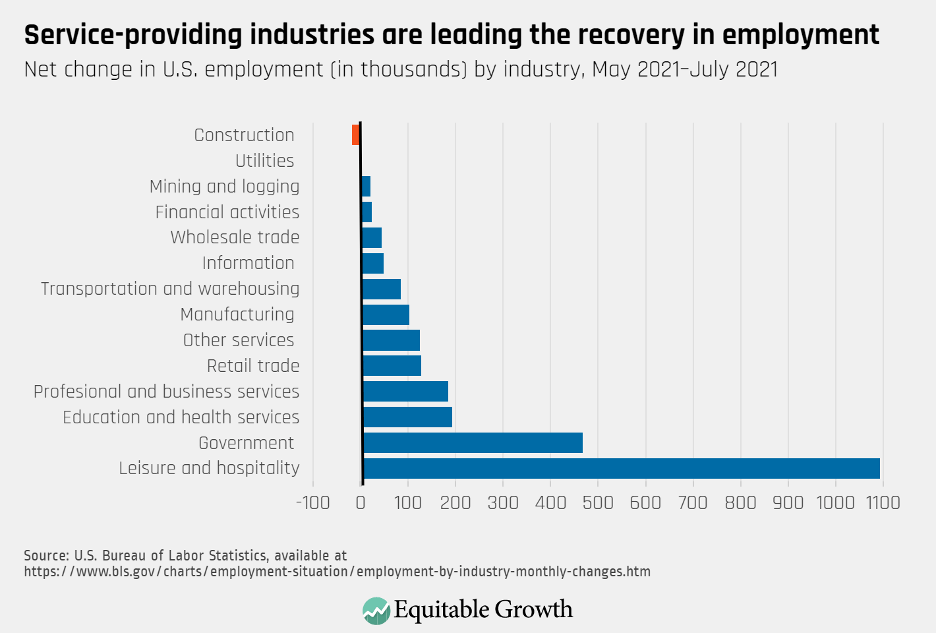

Across industries, July’s employment gains were led by the leisure and hospitality sector, which added 380,000 jobs. Government, education and health services, and professional and business services also saw important gains, creating 240,000, 87,000, and 60,000 jobs, respectively.

But while many industries experienced robust job growth in the past few months, construction is one of the two major sectors to have actually experienced declines in net employment this summer, though the sector did add 11,000 workers in July. An incomplete and uncertain recovery in the industry is likely to be particularly tough on Latinx workers, who represent 30 percent of the construction workforce despite accounting for less than 18 percent of all U.S. workers. Between mid-April and mid-July the construction industry shed 18,000 jobs—significantly more than the 1,400 jobs lost in the utilities sector. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

What is slowing down job growth in the construction industry? Part of the answer is that despite a hot housing market, supply chain disruptions and rising cost of key materials are putting the brakes on new construction, especially in the non-residential sector. According to a recent survey by the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, big price increases for important inputs such as wood, steel, and aluminum are the major factors driving uncertainty and dampening demand for future projects.

In addition—and despite reports of so-called labor shortages by employers and industry associations—demand for construction workers does not appear to be unusually high. The latest available data show that while in the overall economy there is now about one job opening for every unemployed worker, there are almost 2 unemployed construction workers for every unfilled construction position.

The construction industry fared better during the coronavirus recession than in previous downturns, but long-term challenges remain

Employment in goods-producing sectors such as construction tends to be especially sensitive to fluctuations in the business cycle. The reason is that during downturns, a slowdown in economic activity translates into reduced demand for new construction projects, creating a negative feedback loop in which uncertainty further depresses investment and puts workers at risk of losing their jobs.

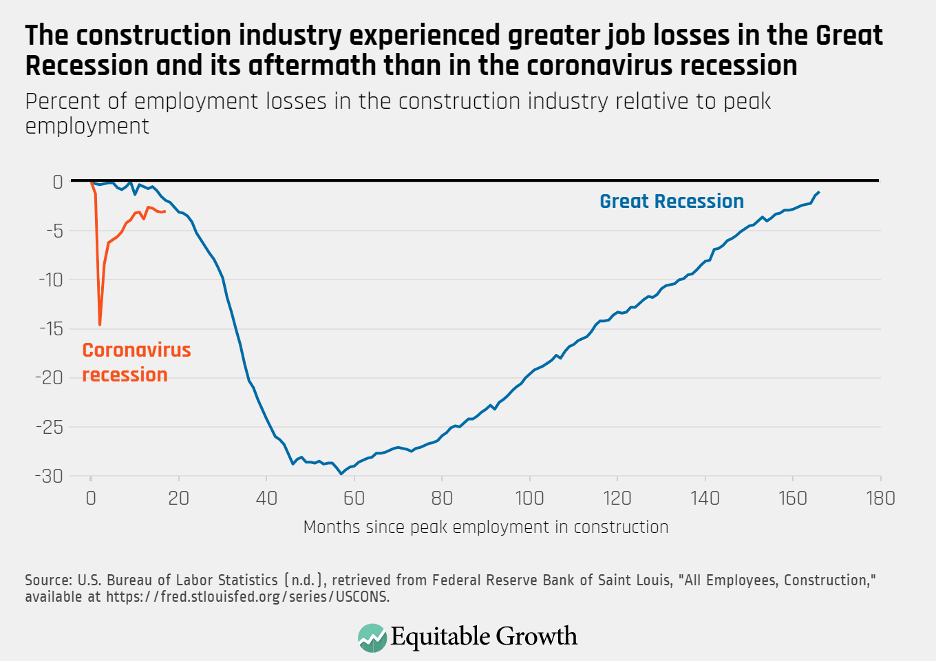

The coronavirus recession, however, hit service-providing industries much harder, and job losses in construction have been less severe than in the last economic crisis. During the Great Recession of 2007–2009 and the housing market crash of 2008–2011, the construction industry lost 2.3 million jobs from the peak of employment in mid-2006 to the trough of employment in early 2011. While the economy-wide peak-to-trough job losses were much greater during the coronavirus recession than during the Great Recession and its aftermath, the drop in construction employment was not as dramatic. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

Yet changes brought about by the pandemic could drive long-term disruptions to the industry. A Bureau of Labor Statistics analysis estimates that if a shift to telework lowers demand for new office space, job growth in the construction sector will slow down in the coming decade. Weak employment growth in this sector would reduce opportunities for what a team of researchers at The Brookings Institution call “skyway occupations”—jobs that have relatively low barriers of entry, often do not require a college degree, offer opportunities for career advancement, and which can act as stairways for better, higher-paying jobs.

The construction sector is an example of the ways in which the coronavirus crisis made already precarious work even more insecure

The construction industry pays above-average wages, its workers are slightly more likely than the average U.S. worker to be a part of a union, and the sector can be a source of jobs that offer a pathway to upward occupational mobility. Yet the current health and economic crises also highlight the many ways in which construction workers face precarious working conditions.

Workers in big occupations within the industry such as construction laborers are among the most likely to experience injuries and illnesses at work. A study by researchers at the University of California, San Francisco finds that workers in this occupation also are among the most exposed to the coronavirus. Latinx workers, who represent a large share of the industry’s workers, have higher injury and fatality rates than the overall workforce. And climate change and excessive heat are making construction work even more dangerous.

That foreign-born workers are also overrepresented in the industry means that some of the workers more likely to need employment protections such as paid sick leave are also among the least likely to access those benefits. Illegal misclassification of workers as independent contractors and unpredictable gaps in work also reduce construction workers’ earnings and reduce their economic security. According to a report by the Workers Defense Project on the working conditions of construction workers in the South and Southwest, a whopping 55 percent of workers do not have access to workers’ compensation and 53 percent reported that they do not have access to employer provided health insurance.

Research also shows that construction saw an especially large increase in minimum wage violations during the Great Recession. The research points to the need to have an effective enforcement of labor protections always, and especially during downturns such as the coronavirus recession.

In addition, Latinx workers, Black workers, women workers, and self-employed construction workers all experienced disproportionate employment declines at the onset of the recession—more evidence that even within industries, already vulnerable workers have been more exposed to the economic pain brought about by the coronavirus crisis.

Per the latest Employment Situation Summary, the U.S. economy continues to be 5.7 million jobs down compared to February 2020 at the start of the coronavirus recession. After months of robust but uneven job gains, economic policy priorities for rebuilding the U.S. economy must center job quality. Policymakers have coalesced around the need for physical as well as care infrastructure, but the workers who will build the country’s much-needed roads, schools, hospitals and other care facilities, and homes often face increasingly dangerous working conditions and little economic security. To meet the construction needs of the present and future, construction workers need strong and enforced labor standards and robust unions.

Perhaps most immediately, they need access to workplace benefits, including health insurance and sick leave, as they continue to work in an ongoing pandemic. Ensuring construction workers are fairly compensated and do their jobs under safe working conditions will both promote the creation of good-quality opportunities, job security, and boost economic growth.