Is weak U.S. wage growth all because of who’s getting jobs?

The weak wage growth in the United States continues to confound some economists. Although the U.S. unemployment rate is under 5 percent—many economists’ estimate for the lowest possible rate of unemployment that won’t trigger accelerating inflation—U.S. wage growth is far from robust. And while the traditional Phillips curve would have us believe that high wage growth is right around the corner, it hasn’t arrived yet. Perhaps this is because the unemployment rate isn’t as good a measure of labor market slack as in the past. Or, as a new article from the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco argues, it may be because the composition of workers in the labor market is pushing down measured wage growth.

Why would the change in the composition of workers over time affect the measurement of wage growth? Consider the changes in the percentage of the workforce in certain occupations. Let’s say a lot of jobs are created in high-paying occupations over the course of an economic recovery. The workforce would then have a higher average wage, because more workers would be in higher-paying jobs, but that tells us nothing about the pace of wage growth within occupations. While the average wage growth would be high, wage growth for workers in those occupations might have been quite low.

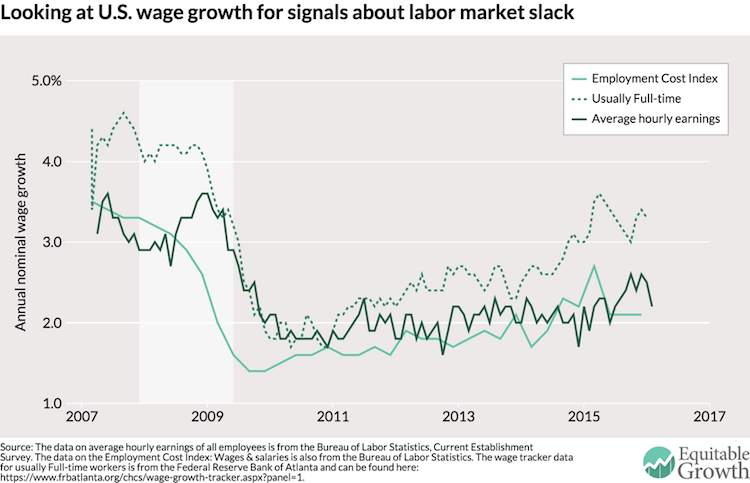

Our nominal measures of wages and wage growth, such the Current Establishment Survey’s average hourly earnings, don’t account for changes in worker composition. But the Employment Cost Index tries to account for this issue by holding the occupational mix of workers constant at some ratio in the past and then measuring the pace of wage growth for that combination.

That’s not the only kind of compositional issue that might affect measured wage growth, however. In an economic letter for the San Francisco Fed, Mary Daly and Benjamin Pyle of the bank and Bart Hobijn of Arizona State University argue that other compositional effects need to be considered as well. First, there’s the Baby Boomers. The increase in retirement means that older workers, who are disproportionately higher-wage earners, are no longer included in the average wage, which will push down measured average wage growth. At the same time, many workers are moving from involuntary part-time work to full-time work. Because most of these new full-time jobs are relatively low-wage jobs, that will also pull down measured wage growth.

What should we look at then to understand wage growth? Daly, Hobijn, and Pyle argue for a measure that looks at the wage growth of workers who are continuously employed full-time. Luckily, the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta produces just such a metric. Note that this measure tracks a specific worker over time, so it’s not a cross-sectional measure like others that look at wage growth. The graph below shows annual wage growth according to the Atlanta Fed wage growth tracker for “Usually Full-time” workers, the Employment Cost Index, and the average hourly earnings for all private-sector workers from the Current Establishment Survey.

The wage tracker shows that wage growth ticked up in 2014 and is much higher than even the Employment Cost Index measure, which controls for the composition of occupations. Wage growth for usually full-time workers, however, seems to have decelerated in the second half of 2015. Also note that while the wage tracker data shows stronger wage growth, nominal wage growth for usually full-time workers is still below its pre-recession levels.

But it’s still not clear that only focusing on the constantly employed is necessarily a better indicator of labor market slack. If more workers are getting pulled into full-time employment, that’s a sign there’s still labor market slack. And the resulting lower wage growth would still be a sign of remaining labor market slack. Maybe these different wage measures are picking up the decline in different kinds of labor market slack, or stages of slack.

First, slack declines enough that already-employed workers start to see increases in their wages and earnings. That increase induces employers to find part-time workers who’d like a full-time job or even workers outside the labor force. Looking at measures like the Atlanta Fed’s may tell us about the progression through this first stage, and then the level of wage growth according to more traditional measures could tell us about the second stage. The first is a signal that slack is starting to abate, and the second is a signal that it’s mostly gone.

But when it comes to the most important question of the moment, most measures indicate that labor market slack still remains. The labor market is getting stronger, but it’s still not strong.