Factsheet: Unemployment Insurance and why the effect of work disincentives is greatly overstated amid the coronavirus recession

Under the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security, or CARES, Act,the Pandemic Unemployment Compensation program added a $600 weekly boost to Unemployment Insurance payments. Despite being one of the most effective policy responses to the coronavirus recession yet, the enhanced payments are set to expire at the end of July. The idea that Unemployment Insurance creates incentives for workers to remain unemployed has emerged as the main argument against extending the additional weekly $600, with critics arguing that generous benefits are “undermining the economic recovery.”

As this factsheet points out, current labor market indicators show jobless benefits have a negligible effect on unemployment levels. But the enhancements to Unemployment Insurance have a big impact on the economy and have set in motion a virtuous cycle that helps workers weather an economic crisis while keeping demand for goods and services from plummeting. Here are the facts.

The coronavirus health crisis—not enhanced unemployment benefits—are behind the spike in unemployment

Even after strong employment gains in May and June, the U.S. economy has lost 15 million jobs since February, and new unemployment claims have stood above their Great Recession high for 15 straight weeks. The absence of safe working conditions, a sharp drop in consumer spending, and lack of support for parents and caregivers are preventing millions from working.

More specifically:

- Using real-time data from small businesses, a team of economists find that the states where benefits replace a greater portion of workers’ wages experienced the smallest drop in hours of work in March and, as of early June, the strongest recovery. Another analysis finds that receiving jobless benefits had no effect on workers’ likelihood of finding a job.

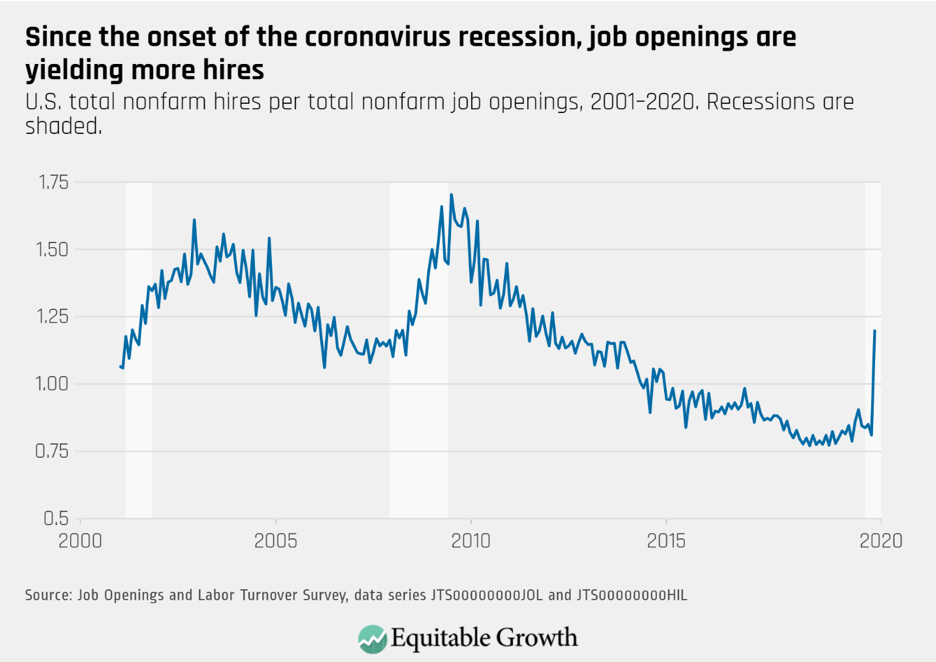

- The U.S. vacancy yield, which measures the ratio of hired workers for every job opening, shows that employers are now filling open positions faster than at any point since February 2012. Lack of opportunities to work, not a disincentive to work, are keeping unemployment elevated. (See Figure 1.)

- Data from Indeed.com—a widely used job-search website—show that there were 23 percent fewer job openings in early July 2020 than in the same moment the previous year. Data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics show that there are now almost four unemployed workers for every job opening.

Figure 1

Concerns about work disincentives overstate the negative impact of jobless benefits on employment and minimize the positive impacts evident in economic research

There is no academic consensus on the effect of the duration or generosity of unemployment benefits on employment. Research shows, however, that any effect these benefits might have on overall unemployment is small and likely to be weaker in downturns than in booms. Consider:

- Cutting-edge research on the duration of Unemployment Insurance finds that the expansion of jobless benefits during and after the Great Recession had a negligible effect on unemployment rates. When comparing similar workers facing similar labor market conditions, states where workers could get benefits for longer did not have higher rates of unemployment.

- By providing a lifeline when jobs are scarce, Unemployment Insurance can keep workers engaged in searching for jobs even when jobs are hard to find, keeping many from dropping out of the labor force altogether.

Unemployment Insurance provides liquidity to the workers who need it the most, getting cash in the hands of those more likely to spend it. Those who have been hardest hit by the crisis—Black, Latinx, and low-income households—are less likely to have the liquid financial assets needed to maintain their consumption when their earnings suddenly go down.

Until the coronavirus pandemic and recession are under control, rolling back unemployment benefits will exacerbate the public health crisis and deepen the downturn

Under normal circumstances, Unemployment Insurance allows workers to put food on the table as they search for suitable work, supporting overall economic activity. In the context of a global pandemic and the sharp recession it sparked, providing workers with time and financial resources as they search for suitable work is even more crucial. Specifically:

- Without adequate health and safety workplace standards, face-to-face jobs will put millions of workers at risk. Workers need time and resources to search for suitable work that will not jeopardize their health or public health.

- In the economics literature, the concept of compensating wage differentials describes the additional earnings needed to offset the negative risks associated with some jobs. The true costs to workers of being exposed to a deadly virus in a pandemic is not reflected in the pre-pandemic wage levels used to calculate benefit amounts. Enhanced Unemployment Insurance allows workers to make decisions based on safety rather than desperation during the pandemic.

- The Economic Policy Institute estimates that extending Pandemic Unemployment Compensation payments through mid-2021 would provide 5.1 million jobs by maintaining demand for goods and services.

The emphasis on work disincentives serves to exclude Black and low-wage workers and reflects racist biases against low-income workers of color

As with other safety net programs, opposition to a robust Unemployment Insurance system often acts to prevent workers of color from receiving their fair share of unemployment benefits. This is especially true for Black workers. Consider:

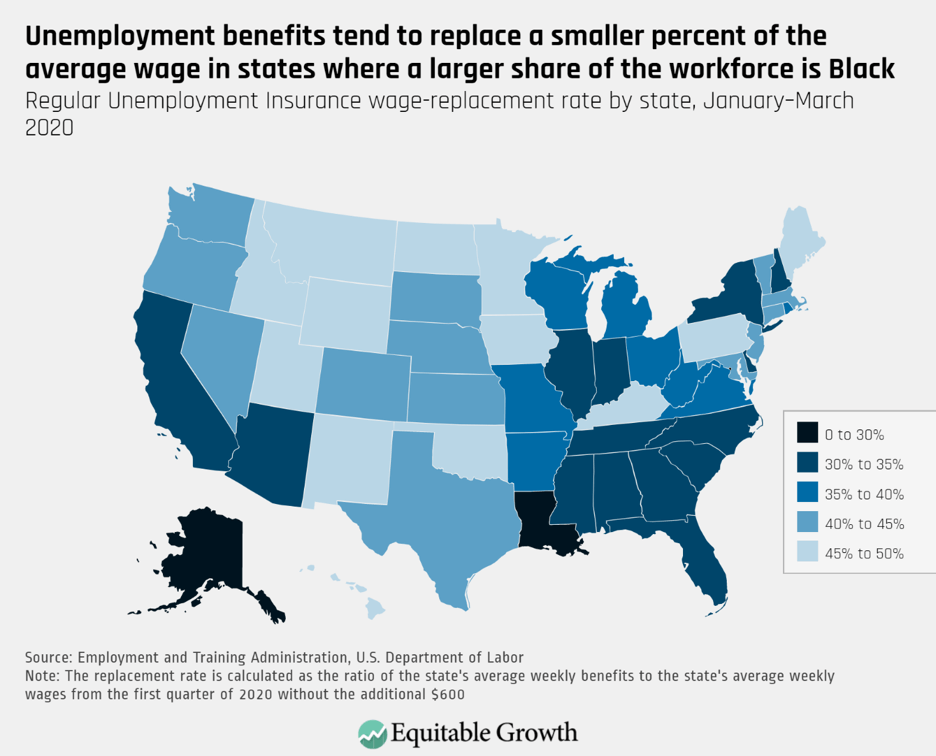

- Despite applying for Unemployment Insurance at similar rates than unemployed White workers, unemployed Black workers—and especially unemployed Black women workers—have been much less likely to receive benefits. States with a higher share of Black workers tend to have less generous jobless benefits. For Black workers, an estimate shows, the average maximum weekly benefit is $40 short of that received by White workers. (See Figure 2)

Figure 2

- Depending on the state, the withdrawal of the additional $600 would lead to a median cut in benefits of 52 percent to 72 percent. The drop would be of 71 percent in Arizona, 71 percent in Louisiana, and 72 percent in Mississippi.

Conclusion

As a number of states reinstate lockdowns due to the recent surge in coronavirus cases and COVID-19 deaths, the prospect of a quick economic recovery is becoming increasingly unlikely. Concerns about work disincentives fail to recognize that job displacements have consequences beyond the loss of wages. Most workers find inherent value in their work and care about benefits, career advancement opportunities, and their long-term economic security.

If Congress lets the Pandemic Unemployment Compensation program expire, then those who have already been hardest hit by the downturn—Black workers, Latinx workers, women workers, and low-wage workers—will be most affected, making the current crisis longer and more severe.