Competitive Edge: Judge Kavanaugh – Would he increase the divide between the public and judicial debate over antitrust enforcement?

Antitrust and competition issues are receiving renewed interest, and for good reason. So far, the discussion has occurred at a high level of generality. To address important specific antitrust enforcement and competition issues, the Washington Center for Equitable Growth has launched this blog, which we call “Competitive Edge.” This series features leading experts in antitrust enforcement on a broad range of topics: potential areas for antitrust enforcement, concerns about existing doctrine, practical realities enforcers face, proposals for reform, and broader policies to promote competition. Howard Shelanski and Michael Kades have authored our second entry.

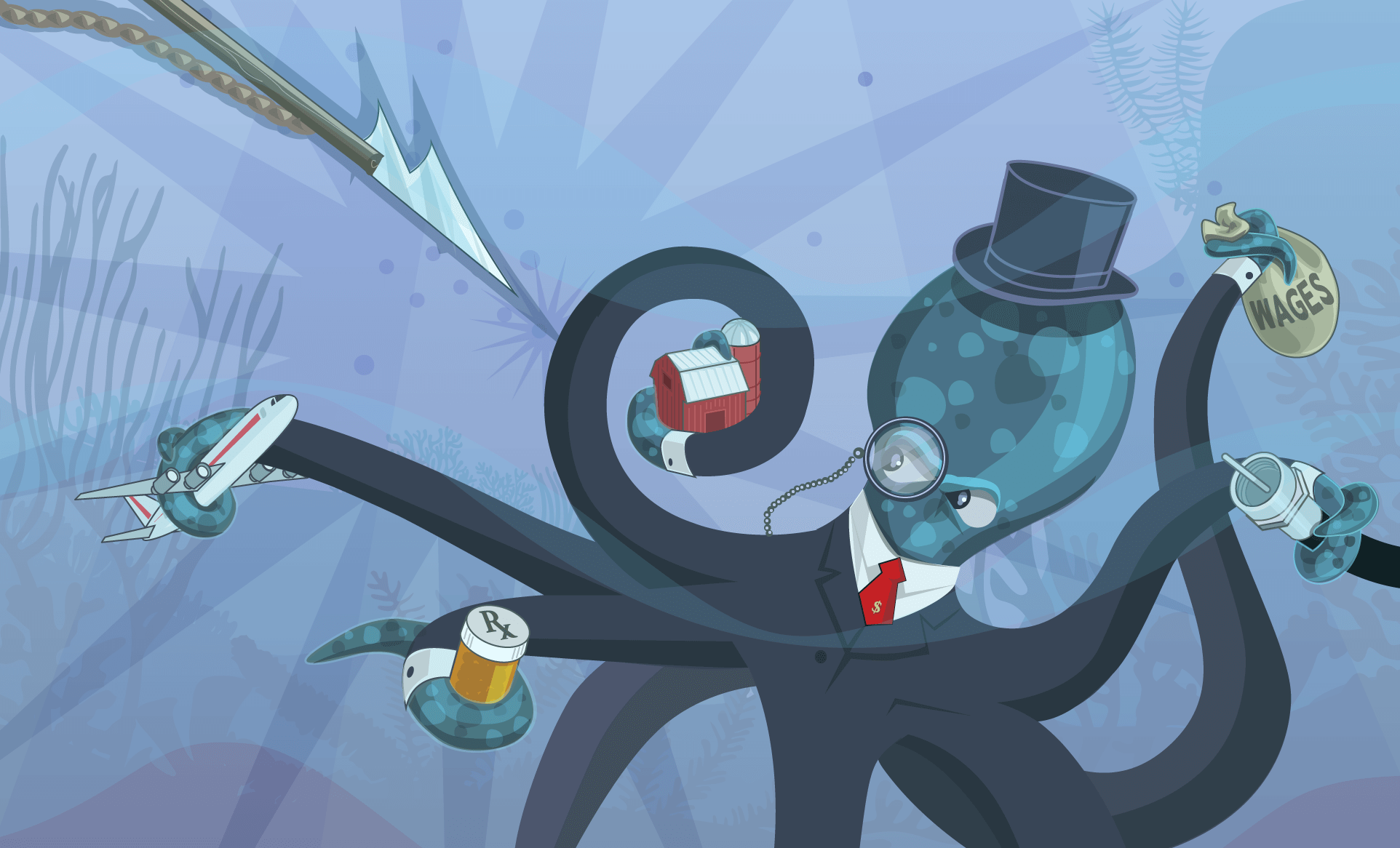

The octopus image, above, updates an iconic editorial cartoon first published in 1904 in the magazine Puck to portray the Standard Oil monopoly. Please note the harpoon. Our goal for Competitive Edge is to promote the development of sharp and effective tools to increase competition in the United States economy.

For the first time in decades, antitrust policy is part of the national political debate. Widespread concerns about the conduct of digital platforms, arguments over whether a narrow focus on prices is missing larger competitive harms, and studies showing trends toward increased market concentration and higher profit margins have all motivated calls from diverse quarters for stronger U.S. antitrust enforcement. The data and concerns underlying this public discussion are rightly subject to serious debate, yet the pro-enforcement motivation evident in the current policy debate differs starkly in direction from the U.S. Supreme Court’s recent antitrust jurisprudence.

Over the past decade, the Supreme Court has, with one exception that we discuss below, followed a path of reduced enforcement, reflected in decisions weakening prohibitions against vertical restraints (Leegin Creative Leather Products Inc. v. PSKS Inc.), limiting the role for antitrust in regulated industries (Credit Suisse Securities (USA) LLC v. Billing), and increasing burdens on plaintiffs challenging conduct by “multisided platforms” (Ohio v. American Express Co.). Senator Amy Klobuchar (D-MN) underscored this divergence when questioning Judge Brett Kavanaugh in his recent Supreme Court confirmation hearings about how he might further limit antitrust doctrine. Although antitrust issues are not a central issue in his confirmation, the evidence is strong that Judge Kavanaugh would cement a five-judge conservative majority that would likely raise, not lower, barriers to antitrust enforcement.

The delicate balance on the Supreme Court, in which Kavanaugh would become a factor, is evident in the last two substantive antitrust cases the Supreme Court decided. In FTC v. Actavis, Inc., which is the exception we refer to in the paragraph above, a 5-to-3 majority (Justice Samuel Alito was recused) found that patent settlements can violate the antitrust laws in a decision that favored enforcers. In Ohio v. American Express Co., a 5-to-4 majority ruled that the plaintiffs had failed to establish anticompetitive effects, increasing the burden of proof at least in cases involving so called two-sided transaction markets. In each case, Justice Anthony Kennedy, whom Kavanaugh would replace, was the deciding vote. The available evidence suggests that Kavanaugh would side with the more conservative Justices in similar cases down the road.

Although Kavanaugh has penned only a few substantive antitrust decisions, those decisions reflect the conservative economic approach of the so-called Chicago School, which refers to a group of academics who began criticizing antitrust enforcement in the 1960s from an efficiency-oriented, neo-classical economic perspective, some of whom went on to become judges, such as Robert Bork, Frank Easterbrook, and Richard Posner. Through their lens, the Chicago School argued that many previously prohibited commercial activities were more likely to reduce prices for consumers than to harm competition and ushered in more lenient legal rules and policies.

More recently, those legal rules have been criticized for going too far and allowing businesses to get away with too much anticompetitive activity. Whether one agrees with that criticism, it is an important question whether a new Supreme Court Justice makes it more or less likely that the federal courts will shift to a more enforcement-oriented antitrust jurisprudence.

In the case of Judge Kavanaugh, the answer seems clearly to be no. In recent decisions, he has taken a strongly Chicago-School approach, invoking Judge Bork’s Antitrust Paradox in dissents that, if they were to become law, would weaken antitrust law’s limitations on horizontal mergers (mergers between competing firms) in two important ways. 1 First, he would weaken the presumption of illegality that arises when the government makes its initial case for harm. Second, he has articulated a narrow view of what evidence an enforcement agency or plaintiff can use to define a market. Let’s look at each of these issues in turn.

Weakening the presumption

Under current merger doctrine, the government must establish a prima facie case that a merger is anticompetitive, usually by showing it will substantially increase concentration in a relevant market. The defendants may then argue that the merger would create efficiencies that will outweigh the harm. Typically, courts are skeptical of efficiencies and require strong evidence that they will in fact materialize and offset any harm to competition.

Judge Kavanaugh’s dissent in the Anthem case reflects an assumption that efficiencies are likely and large. The case arose out of the U.S. Department of Justice’s challenge to Anthem Inc.’s proposed acquisition of Cigna Corp. The district court found that the health insurance market for large employers was presumptively anticompetitive, but then it rejected the merging parties’ defense—that the merger would create efficiencies and those procompetitive benefits would outweigh any harms. The district court rejected the defense expert’s opinion and found that both internal documentary evidence from Anthem and testimony from Cigna contradicted the efficiency defense. On appeal, the majority of the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals agreed with the district court, stressing that the efficiency defense was a factual issue and could be reversed only if there were clear errors. The majority explained in detail why the efficiencies evidence was limited and failed to meet the requirements for rebutting the presumption of harm. 2

In dissent, Judge Kavanaugh agreed that the merger was presumptively anticompetitive, but he believed the defendants had met their burden in providing a procompetitive justification for the deal: the combined company would negotiate lower prices from health providers that would be passed along to its customers. Relying on the defendants’ expert and a consultant report, Judge Kavanaugh concludes, “In short, the record overwhelmingly establishes that the merger would generate significant medical cost savings for employers in all of the geographic markets at issue here … and employers would therefore spend significantly less on healthcare costs.” 3

In Judge Kavanaugh’s assessment, the district court should have flipped the burden back to the federal government, which had failed to return the volley. He wrote: “By contrast, the Government’s expert, Dr. Dranove, never did a merger simulation that calculated the amount of the savings that would result from the lower provider rates and be passed through to employers. … So we are left with Anthem-Cigna’s evidence showing $1.7 to $3.3 billion annually in passed-through savings for employers.” 4

On the one hand, the dispute between the majority and Judge Kavanaugh may be over the application of the standard of review, or how much evidence is required for an appellate court to overturn a district’s factual finding. But it is well established that where the evidence admits two different inferences, the trial court’s conclusion stands, even if the reviewing court would have chosen differently. On the other hand, the dispute may be over substantive antitrust law. Judge Kavanaugh’s dissent could reflect a view that, once defendants provide an estimate of savings that offset the potential harm, the government must offer a contrary estimate; it is not enough for the district court itself to reject the defendants’ efficiencies evidence.

Market definition

While Judge Kavanaugh’s dissent in the Anthem case suggests lowering the burden on defendants to establish an efficiency defense, his dissent in Federal Trade Comm’n v. Whole Foods suggests he would require a higher burden on the government to establish a presumption of illegality in a merger case. In that case, the district court had denied the Federal Trade Commission a preliminary injunction against Whole Foods’ acquisition of Wild Oats on grounds that the Commission failed to prove its definition of the relevant market as consisting of “premium natural organic supermarkets” rather than all supermarkets. On appeal, the majority reversed that decision, finding that the district court abused its discretion in denying the injunction. Judge Kavanaugh would have affirmed the district court’s ruling.

The dispositive issue in the case was showing what the Federal Trade Commission needed to make to obtain a preliminary injunction and whether the evidence satisfied that standard. That issue was, and continues to be, highly contentious, and Judge Kavanaugh’s dissent again indicated a view that the government should bear a relatively high burden of proof.

Importantly, Judge Kavanaugh appears to find that the government must have pricing evidence to prove a relevant market, arguing that: “In the absence of any evidence in the record that Whole Foods was able to (or did) set higher prices when Wild Oats exited or was absent, the District Court correctly concluded that Whole Foods competes in a market composed of all supermarkets.” 5 While courts often do rely on pricing evidence to define markets, such evidence is not always available and is not always required.

Indeed, the government’s economic expert (Kevin Murphy, from the University of Chicago) presented sophisticated economic analysis and the Federal Trade Commission presented significant documentary evidence in support of the Commission’s narrower market definition. If Judge Kavanaugh believes that such evidence is insufficient to meet the government’s burden—at least in the absence of quantitative price effects—then the Supreme Court, with Judge Kavanaugh’s membership, could change merger jurisprudence, making it less hospitable to stronger enforcement.

One might agree or disagree with Judge Kavanaugh’s positions in the above dissents, just as one might agree or disagree with recent calls for stronger antitrust enforcement. Our purpose here is to demonstrate why Judge Kavanaugh’s presence on the Supreme Court would likely widen rather than narrow the divergence between the direction of the Supreme Court and the direction of the public debate with respect to antitrust enforcement.

—Howard Shelanski is a professor of law at Georgetown University and a partner at the law firm Davis Polk & Wardwell LLP. Previously, he served as the Administrator of the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs at the Office of Management and Budget in President Barack Obama’s White House. Michael Kades is the director for Markets and Competition Policy at the Washington Center for Equitable Growth. Prior to joining Equitable Growth, he worked as antitrust counsel for Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D-MN), the ranking member on the Senate Judiciary Subcommittee on Antitrust, Competition Policy and Consumer Rights

End Notes

1. United States v. Anthem Inc., 855 F.3d 345, 366 (DC Cir. 2017) (Kavanaugh J., dissenting); Federal Trade Commission v. Whole Foods, 548 F.3d 1028, 1052, 1058-59.

2. Anthem, 855 F.3d at 365.

3. Anthem, 855 F.3d at 376. (Kavanaugh J., dissenting)

4. Anthem, 855 F.3d at 374. (Kavanaugh J., dissenting)

5. Federal Trade Commission v. Whole Foods, 548 F.3d at 1054.