Neil Irwin writes: This is how history should judge Ben Bernanke:

The most common knock on Bernanke’s crisis performance was his failure (along with Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson and then-New York Fed chief Timothy Geithner) to prevent the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy…. It’s a fair criticism, except for this: I have interviewed enough people and read enough internal e-mails from that period to conclude that no one at the time had come up with a plan to resolve Lehman that was legal and actionable. The Lehman failure wasn’t a case of Bernanke and his fellow officials facing a choice and deciding wrong. They weren’t able to come up with a better option…

On March 15, 2008, Lehman Brothers was both liquid and solvent.

On September 15, 2008, Lehman Brothers was both illiquid and–so the story goes–too insolvent for the Federal Reserve to be able to claim that its loans to keep Lehman operating were simply providing liquidity to a fundamentally-solvent institution.

By continuity, at some point between March 15 and September 15, there was a last day on which the Federal Reserve had the power to provide the money to force an orderly liquidation of Lehman. On that date, they should have forced its liquidation. They did not.

The first rule of being a lender of last resort is that you do not get yourself into a position where you cannot act as a lender of last resort when a systemically-important financial institution fails. Paulson, Bernanke, and Geithner broke that rule when they let Lehman slide into insolvency at some date between March 15 and September 15, 2008, and they have never explained why they let their last opportunity to resolve Lehman pass by.

And then Neil Irwin says that it did not matter, anyway:

If they had found a way to save Lehman, soon enough there would have come another breaking point, with another institution on the brink and deep-seated demand to let it fall…

And that makes no sense at all. If letting Lehman fail didn’t hurt things, why take over AIG two days later? Why set up the TARP? Either these policies matter–in which failure to take the right policy steps at the right time is a mistake. Or these policies don’t matter–in which case why take any policy steps at all?

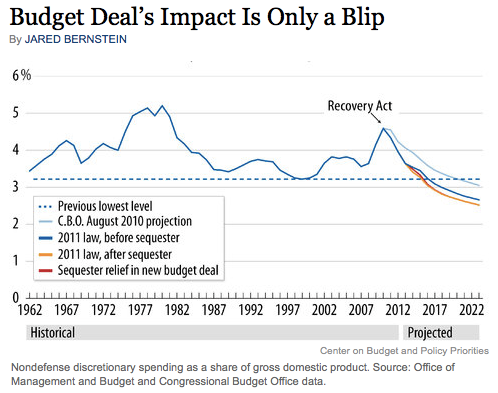

Jared Bernstein:

Jared Bernstein: