Information from the very sharp Eric Toder: The House Ways and Means Tax Bill Would Raise the National Debt to 123 percent of GDP by 2037: “The Tax Policy Center estimates that the House Ways and Means Committee’s version of the Tax Cut and Jobs Act (TCJA)…

…over the first decade… increases the deficit by $1.7 trillion…. Between 2028 and 2037, the TCJA would reduce net receipts by $1.6 trillion and add $920 billion in additional interest costs. Over the entire 20-year period, the combination of reduced revenues and higher interest payments would raise the federal debt held by the public by $4.2 trillion…

This is based on:

the baseline economic and budget estimates in the Congressional Budget Office’s (CBO) March, 2017 long-term and June, 2017 updated 10-year budget projections…

But, of course, if the Trumpublican plan is passed, the best forecast of how the economy would evolve would not be the baseline CBO spring 2017 projections, but would be different. How different, and in which direction?

The best way to explain what professional economists think is to follow turn-of-the-twentieth-century British economist Alfred Marshall and divided the analysis up into four “runs”, each of which corresponds to a different forecast horizon, and in each of which the dominant economic factors at work are different. Call these the “short run”, “medium run”, “long run”, and “very long run”. And be aware that this separation is a heuristic device to aid in understanding. In the real world, all of the factors are operating all at once over time, so that even in the “short run” it is the case that “long run” factors will have a (small) influence. Moreover, the “runs” do not always come in sequence: sometimes the “long run” is right now.

With that caveat, the “runs” are:

- The “short run”, usually of zero to four years. In the short run, the economy is not or is not necessarily at “full employment”. Production can be below or above the current value of its sustainable productive potential, and changes in policy can either kick spending down (in which case production falls, unemployment rises, and inflation slows), or kick spending up (in which case production rises, unemployment falls, and inflation speeds up). Over the short run these effects of policy changes on the level of production, employment, and inflation are the dominant impacts.

-

The “medium run”, usually of one to fifteen years, in which price levels and standard policy reactions have had time to adjust and so match production to the economy’s sustainable potential and match inflation to its generally-expected value, but in which there has not yet been time for stocks of productive resources to substantially adjust to policies. Over this medium run, the dominant effects of policy changes are on the division of production and spending between consumption, investment, government purchases, and net exports, plus the concomitant effect of those shifts in the distribution of production on the medium-run rate of economic growth.

-

The “long run”, typically of ten to thirty years, in which stocks of productive resources have adjusted to changed incentives. Price levels and standard policy reactions have adjusted and matched production to potential and inflation to expectations. Adjustment has taken place so that government budget and international balance conditions are no longer out of whack with unsustainable deficits or surpluses. Shifts in the distribution of production have raised or lowered relative resource stocks so that they are no longer changing relative to the economy. s a result, in the long run the value of the economy’s productive potential has jumped up or down relative to its previous baseline growth path.

-

The “very long run”, in which demographic and technological change factors that determine not jumps up or down in the level of sustainable productive capacity but rather the evolution of the economy over generations.

What are the likely effects of the Trumpublican plan, if implemented, in these four “runs”?

First, there is no short run argument that the bigger government deficits produced by Trumpublican plan will boost the economy. In order for a plan that increases deficits to boost the economy, three things would have to all be true:

- The larger deficits must either generate more purchases of goods and services directly—by the government buying more stuff—or get more purchasing power into the hands of people who have a high propensity to spend extra cash because they feel short of cash. The Trumpublican plan gets many into the hands of the rich, who do not feel short of cash.

-

Production in the economy must be low relative to sustainable potential, so that extra spending actually does put workers without jobs to work in factories currency standing idle. Right now it looks as though the economy is close to if not at its sustainable potential—but there is an ongoing debate about that.

-

The Federal Reserve must believe that production in the economy is low relative to sustainable potential. It must, then, be willing to cry “Havoc!”, and let slip the dogs of a higher-pressure economy. Right now the Federal Reserve is certain that the economy is very near to if not at “full employment”, and will respond quickly and thoroughly by raising interest rates in order to keep spending on the path it currently envisions.

All of (1), (2), and (3) would have to be true together for there to be a correct argument that the Trumpublican plan would boost economic growth in the short run. (1) and (3) are certainly false. (2) is probably false.

We can, in this case, neglect the short run analysis. It is not there in this case.

Nevertheless, if it were there—if (1), (2), and (3) were true or were to become true—a tax cut would boost production. This short-run argument is completely standard. I see it, for example, on page 319 of my copy of N. Gregory Mankiw: Macroeconomics (9th edition) http://amzn.to/2zelfc2:

Second, the medium run argument is that the Trumpublican tax ct for the rich will not boost but rather be a drag on the economy. It raises the budget deficit by about 0.7% of GDP. That means that private savings that would have gone to finance private investment spending are diverted to the government instead. That deficit increase shifts about 0.5%-points of production out of investment spending, decreases net exports by about 0.2%-points of production, and raises consumption—elite, upper-class consumption, for the rich are the ones to whom the money is flowing—by 0.7%-points of production.

This medium-run argument is completely standard. I see it, for example, on page 74 of my copy of N. Gregory Mankiw: Macroeconomics (9th edition) http://amzn.to/2zelfc2:

The 0.5%-point fall in investment in America will slow economic growth by about 0.05%-point per year: we would lose 10 billion dollars a year of economic growth each year over the next ten years. That would leave real production in a decade some 100 billion dollars a year less—about 1000 dollars a year less per family—than in the baseline forecast. In an economy current currently producing 20 trillion dollars worth of goods and services a year, that would not not an economy-shattering deal. But 1000 dollars a year less in income per family—0.5% lower real production in a decade—would hurt: it would be a poke in the eye with a sharp stick.

Third, the long run argument is that the Trumpublican plan could boost the economy by inducing more investment. It cuts taxes on profits from passive investments, making investing in them more, well, profitable. Thus money should flow in, and some of that money will be used to build buildings and install machines to make workers more productive. This could happen: the right assessment of this argument is “it depends”. For one thing, in the long run the plan is simply one part of the change in the economy and in incentives that the Trumpublican plan will set in motion. The government budget must add up properly in the long run, and so in any long run analysis the tax cuts for the rich must be balanced either now or in the future by spending cuts or tax increases for the non-rich, and those would have their own effects on incentives and thus on productivity. For another thing, who would the increased profits flow to, and who would benefit from increased productivity?

It is possible to roughly and approximately sketch out this long run argument in another standard framework, set out by Paul Krugman in Leprechaun Economics, With Numbers. Assume that we start with an economy with (as the U.S. economy has) 150 million workers, producing 20 trillion dollars of national income each year with the assistance of 80 trillion dollars of capital. Assume further that the pre-corporate-tax rate of return on capital is some 10.0% per year. With a corporate tax rate of 35%, that would give us an after-tax rate of return on capital of 6.5% per year.

Now cut the corporate tax rate to 20%. That would give us an after-tax rate of return on capital of 8% per year if investment and thus the capital stock were to not rise in response to this increase in profitability. But in the long run investment and the capital stock would rise. By how much? Three considerations appear dominant:

- Domestic savings are simply not responsive to rates of return. Lots of economists have looked at the question, hoping to find that increases in profitability call forth increases in domestic savings and thus in investment. They haven’t found much.

-

The U.S. is a huge chunk of the world economy. Figure that changes in after-tax rates of return in the United States drag the required rate of return in the rest of the world up or down in its wake by about 1/3 as much.

-

International capital does chase higher rates of return. But investors in other countries have a limited desire to commit their wealth far away: there is “home bias”. Figure that half of the gap between changes in rest-of-the-world and U.S. returns is closed by international flows of investment.

Take these three considerations into account, and figure that in the long run the after-tax rate of return would fall by about 1/3 of the initial gap between the 6.5% rate before the tax cut and the 8.0% rate after the tax cut. So foreign investment would flow into the United States and push up the capital stock and productivity until the after-tax rate of return were 7.5%—which means that in the long run the pre-tax rate of return on capital would fall to 9.3% from 10%, a proportional decline of 1/14.

As a rule of thumb, to reduce the rate of return on capital by 1/14 requires an increase in the capital stock of 1/14. But only about half total valued capital is machines and buildings: the rest is market power and market position, intellectual property, and other economic quasi-rents. With 40 trillion dollars of machines and buildings, a 1/14 increase is about 3 trillion additional dollars worth of investment and capital.

That extra 3 trillion of capital would boost total annual production by about 300 billion dollars. Of that 300 billion dollars, 225 billion would flow to the foreigners who provided the investment, leaving a 75 billion dollar boost to Americans’ national income—an 0.35% boost. I would be inclined to then double that number: there are valuable benefits to having more investment and more capital, as workers successfully bargain for a share of economic rents created and as more investment strengthens and makes more productive our communities of engineering practice. If I were working for the CEA or the Treasury, I would be comfortable claiming an 0.7% boost in the long run to national income from this tax cut as long as the other changes in policy that made the government’s accounts add up were something (like, say, a carbon tax) that did not impose their own drag on economic growth and well-being (as, say, spending cuts would.

But the medium run effects would still be there in the long run. We would thus have a -0.5% from the medium run; an +0.7% from the long run; and whatever costs would be imposed on the economy by government-budget-adding-up. That looks like a wash to me.

And, fourth, the very long run effects? Those are highly speculative: nobody is confident that they have the right approach to modeling those. I tend to be on the side of those who believe that making the American distribution of income more unequal is harmful to entrepreneurship, enterprise, and growth. A richer superrich are a more politically powerful superrich. Economic growth comes from creative destruction. And in creative destruction it is the current superrich who are creatively destroyed—and thus they use their power and influence to try to block beneficial change. But such arguments are not ones you can take home.

That is the economic analysis of the Trumpublican plan, in basic and approximate form. Everybody serious and professional who is doing an analysis winds up with these pieces:

- A short run near-zero negligible effect.

- A medium run drag on the economy from higher deficits the cumulates to around 0.5% of national income.

- A possible—but far from certain and maybe not even likely—boost to national income (if there is no drag from the other, currently unspecified policy shifts that arrive with the Trumpublican plan in the long run) of about the same magnitude.

- Very long run effects that we do not have a handle on.

If anyone tries to sell you estimates of the impact that differ very much—by orders of magnitude—from those I have just given above, there is something wrong with their model and their analysis. Politely, it is “non-standard”. Impolitely…

Plus, of course: it would be a tax cut for the rich—and by the fact that things add up, a tax increase on and a reduction in useful government services flowing to the nonrich. How big would these effects be? We have estimates from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities:

Chye-Ching Huang, Guillermo Herrera, and Brendan Duke: The Bill’s Impact in 2027: “By 2027… the JCT tables show…

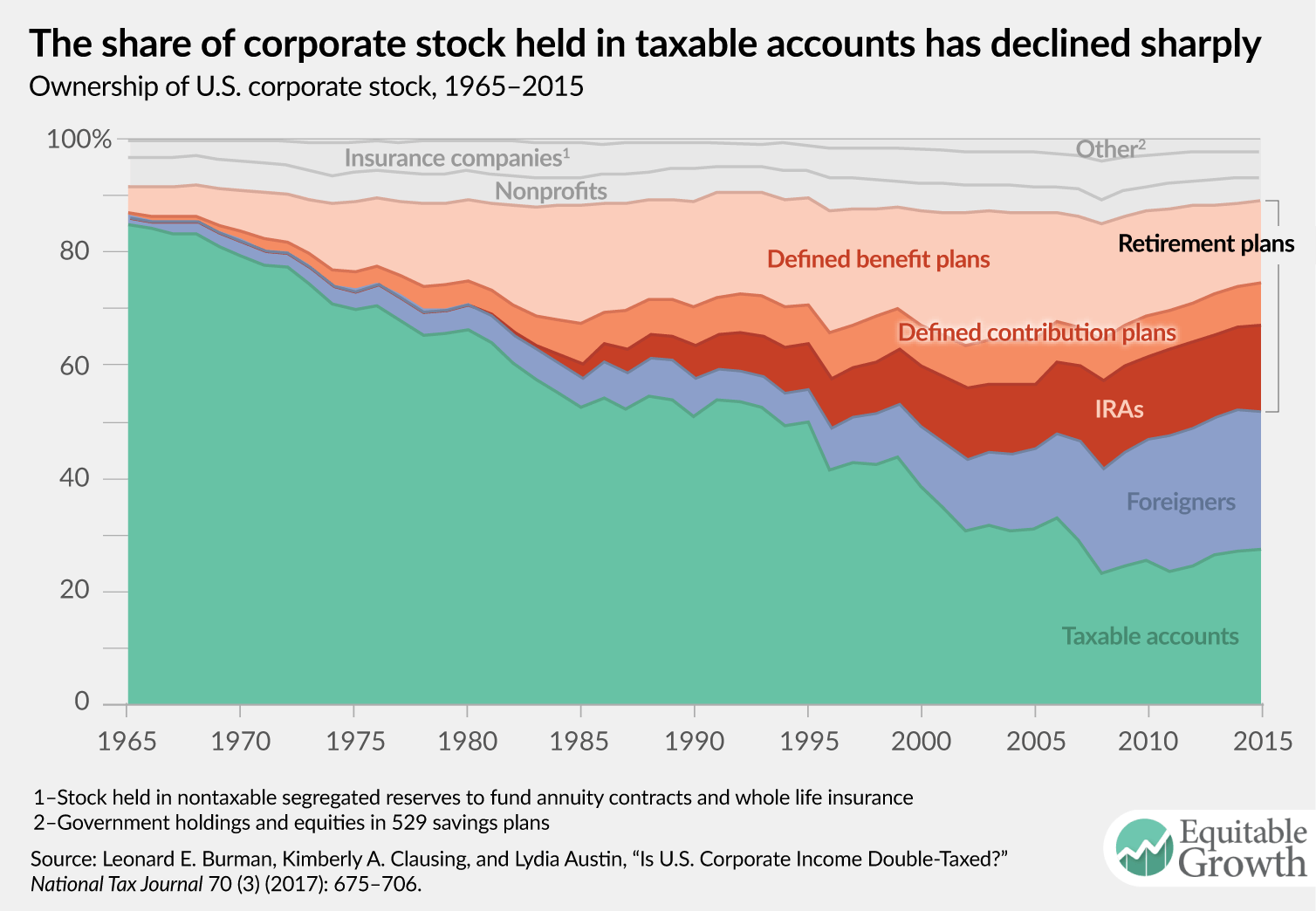

…The highest-income groups would still get the largest tax cuts as a share of after-tax income. Millionaires, for example, would see a 0.6 percent ($16,810) increase… the bill’s permanent corporate tax cuts would primarily flow to wealthy investors and highly paid CEOs and other executives.

Every income group below $75,000 would face tax increases, on average. For example, households between $40,000 and $50,000 would see a 0.6 percent ($310) decline in their after-tax incomes. Many millions more families would face a tax increase in 2027 than in 2025 due to the expiration of such provisions as the increases in the Child Tax Credit and standard deduction. Further, the effect of the chained CPI would grow over time as it would fall further and further behind the tax code’s current measure of inflation…

And the CBPP has a very good track record on these matters.