New data released this morning by the Bureau of Labor Statistics shows remaining weakness in the labor market as both job and wage growth disappointed. There were 126,000 more people employed in the United States in March compared to the prior month, and this weak employment growth was not accompanied by strong hourly wage gains, which grew by only 2.1 percent compared to last year, according to the latest employment and wage data.

The overall unemployment rate stayed the same at 5.5 percent. Many of the job gains were in the retail sector and health care sectors, where employment rose by 25,900 and 30,000, respectively. Over the last three months, the US economy has added a monthly average of 197,000 jobs, and these job gains have not been sufficient to generate substantial wage growth for the overall workforce.

While employment for younger workers saw some positive development in recent months, it fell in March with the employed share of the population aged 16-to-24 years dropping to 48.2 percent from 48.9 percent. Until March the employment situation for younger workers had generally improved alongside the continuing economic recovery, but employment rates for the young still remain at historic lows. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

The employed share of the younger population peaked at 60.2 percent in 2000 and fell sharply during the subsequent recession in 2001. Employment for 16-to-24 year-old workers never recovered from that first recession of the decade, and in the following Great Recession of 2007-2009 it suffered extremely steep losses. At the depths of 2010, employment rates for younger workers reached as low as 44.6 percent. The Federal Reserve should keep in mind that raising interest rates, as it may do this year, will dampen the already low employment prospects of younger workers.

As for wages, last month the hourly pay for workers in the private sector grew at a 2.1 percent annual rate compared to last year, and at an annual rate of 2.8 percent over the past three months, according to the most recent data. Most of the wage growth appears to be in lower-wage industries, such as the retail sector and the leisure and hospitality industries, which include restaurants. Over the last three months, wages in those sectors have grown at annual rates of 3.9 percent and 3.0 percent, respectively.

At the same time, wage growth for all nonsupervisory and production workers appears to be moving the wrong direction and may be aggravating wage inequality. In 2014, year-on-year wage growth averaged roughly 2.3 percent for this portion of the workforce, which comprises about 80 percent of total private-sector employment. This year, however, nonsupervisory wages have slowed, only growing at an average annual pace of under 1.8 percent, according to the most recent data.

The contrast is even sharper when looking back over the past six months: comparing the past three months to the prior three months, nonsupervisory wages have grown at an annual rate of about 1.8 percent. This disturbing slowdown in nonsupervisory wages relative to the overall private sector suggests that wage inequality may be increasing as nonsupervisory workers are generally paid less than other employees.

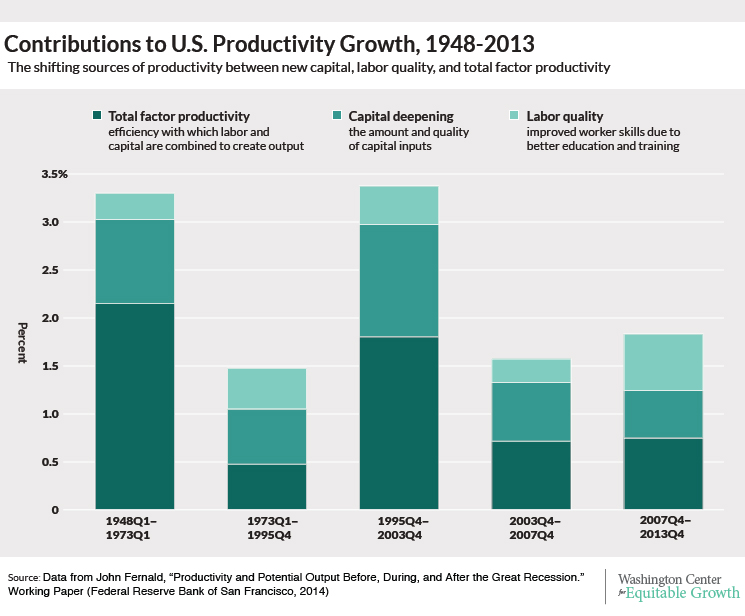

While job gains at the current pace will eventually bring about some wage growth, we should not expect healthy, sustainable wage growth immediately. For workers to maintain or increase their share of income, nominal wages must grow at an annual rate of at least 3.5 percent, assuming the Federal Reserve’s inflation target of 2.0 percent and annual productivity growth of 1.5 percent. Since 1990, nominal wage growth sustainably exceeded the 3.5 percent threshold only when the prime-age employment rate remained above 79 percent.

The employment-to-population ratio for prime-age workers in the past month was 77.2 percent, and the current rate of job gains is increasing this employment rate by about 0.6 to 1.2 percentage points per year. At this pace of employment growth, we should expect persistent, healthy wage gains sometime between the second half of next year and the beginning of 2018, perhaps as late as eight years after the end of the most recent recession.