…commissioned by the city of Los Angeles… [that] found that the benefits of raising L.A.’s minimum wage would outweigh the costs. ‘If the debate were over raising the minimum wage to $13.25 per hour by 2017, we would argue that the Berkeley-IRLE-estimated impacts are the most likely scenario,’ they write…. Los Angeles’s minimum wage currently stands at $9 per hour. After Garcetti proposed raising the minimum wage to $13.25, some members of the council proposed increasing the wage to $15.25 per hour by 2019. Wenger and von Wachter were less confident about the outcomes of that increase because that is longer time period and a larger wage increase than any city has previously experienced. ‘Whatever avenue is chosen, we highly encourage the City Council to follow the example of other city minimum wage ordinances and monitor the economic situation in the city’… developing complementary programs to aid both workers and firms that are most [adversely] affected…

Category: Equitablog

Must-Read: Jason Furman: Smart Social Programs

Must-Read: My view was always–and subsequent research over the past generation has only confirmed my view, at least as I read the research–that the disemployment effects of safety-net programs were vastly oversold. Those who are discouraged appeared to me to be people who also had so many family responsibilities that their participation was of zero or negative societal value in the first place. The underlying subconscious logic behind overselling disemployment effects seemed to me to be one of punishing the poor, and and punishing women who either became pregnant without marriage or who could not keep a man…

…that was in effect from 1911 to 1935…. The program resulted in more education, higher earnings and lower mortality. Social Security data were used to follow program beneficiaries until as late as 2012, allowing researchers to show that the benefits of receiving even a few years of assistance as a child could persist for 80 years or more. Although we do not have 100 years of follow-on data from today’s programs, recent research following children as they entered their 20s and 30s has produced similarly striking findings… the earned-income tax credit… child poverty… low birth weight, raise math and reading scores and boost college enrollment…. The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, formerly known as food stamps, has been shown to have similar benefits for child recipients that can last decades. Receiving Medicaid in childhood makes it substantially more likely that a child will graduate from high school and complete college and less likely that an African-American child will die…. For women, Medicaid participation in childhood is associated with increased earnings….

The benefits often are not captured by short-term outcomes like improvements in children’s test scores, which typically last only a few years before fading…. Second, while program design certainly matters — and can matter a lot — much of the benefit appears to derive from helping low-income families pay for basic needs…. In many cases, the additional tax revenue from the higher long-run earnings generated by the program is sufficient to repay much or even more than all of the initial cost…. Moreover, safety-net programs do not discourage work in any big way…. And child care and pre-K programs make it easier for parents to work in the first place…

Must-Read: Bruce Bartlett: How Fox News Changed American Media and Political Dynamics

: How Fox News Changed American Media and Political Dynamics: “The creation of Fox News in 1996 was an event of deep, yet unappreciated, political and historical importance…

…For the first time, there was a news source available virtually everywhere in the United States, 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, with a conservative tilt. Finally, conservatives did not have to seek out bits of news favorable to their point of view in liberal publications or in small magazines and newsletters. Like someone dying of thirst in the desert, conservatives drank heavily from the Fox waters. Soon, it became the dominant – and in many cases, virtually the only – major news source for millions of Americans. This has had profound political implications that are only starting to be appreciated. Indeed, it can almost be called self-brainwashing – many conservatives now refuse to even listen to any news or opinion not vetted through Fox, and to believe whatever appears on it as the gospel truth.

Do states’ tax policies cause U.S. employees to earn less and employers to earn more?

There are many economic theories about why overall income has moved away from income earned through labor and towards capital, such as stocks and bonds. Economics columnist Robert Samuelson notes that the United States has experienced a $750 billion transfer in income from labor to capital in the past decade alone. The academic world is hard at work trying to figure out what is behind this trend, but finding the kind of causal evidence necessary to identify possible policy proposals to reverse is even more difficult.

That is why Owen Zidar, an assistant professor for economics at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business, and 2014 Equitable Growth grantee, is investigating whether states’ individual tax policies may play a role in the decline of income going to labor. Over the past 50 years, many states, in an attempt to be “business friendly,” have experimented with different kinds of investment and corporate tax credits as a means to encourage investment in their states. Zidar’s research asks whether such tactics by states have resulted in a shift in income from workers to capital owners.

Zidar’s research will build upon earlier research by Loukas Karabarbounis and Brent Neiman of the University of Chicago, who contend that it is cheaper and more powerful technological equipment that is driving the trend. Computers and robotics, they believe, have allowed businesses throughout the world to replace workers with automated systems, thereby reducing the labor share of income. Zidar is exploring the possibility that state tax preferences could have the unintended consequence of making such investments even cheaper, furthering workers’ disadvantage.

To economists, this recent phenomenon of a falling share of income going to labor comes as a big surprise. In 1957, when Nicholas Kaldor outlined six “stylized facts” about economic growth, he included a declaration that there is a roughly constant share of income flowing to labor versus capital. Until it was discovered very recently that the labor share was indeed declining, Kaldor’s point was taken as economic gospel. Today, there are many explanations for what is happening to labor’s share of income, such as Karabarbounis and Neiman’s claim that changes in technology are driving the trend. Other research suggests that globalization, the growth of the finance sector, or the decline of unions are important contributing factors.

Zidar’s research on the role cheaper technology may play in reducing the labor share of income could have important policy implications, especially if it reveals a direct relationship between states’ tax policies and the amount of income going toward labor versus capital. Policymakers might need to reconsider whether these kinds of tax credits are always the most economically prudent—both in terms of paying a fair wage and strengthening the economy overall.

Keynes on Moral Philosophy and Macroeconomic Management, and Diverging Wage Series’ Signals

- Over at Grasping Reality: There Is a Potentially-Important Piece to Be Written About ECI-Wage and Salary Divergence

- Over at Grasping Reality: Today’s Economic History: JM Keynes: Concluding Notes on the Social Philosophy Towards which the General Theory Might Lead

Things to Read at Nighttime on May 8, 2015

Must- and Should-Reads:

: “The IMF… may be full of economists, but it is ultimately run by politicians who may have too many ties to those in the Eurozone. But as Ashoka Mody says, the IMF’s credibility is at stake. It should… focus its efforts on getting the rest of the Troika to be realistic. Above all else, Greece must be helped out of its depression…. Sensible macroeconomists, including those at the IMF, know that makes sense. If Yanis Varoufakis could not achieve this, perhaps the economists at the IMF can do better…”

* : Modern Macroeconomic Methodology

* : The importance of addressing the U.S. racial and ethnic wealth gap

* Morning Must-Read: : The Wire Got It Backwards

* : How Much Finance Is Too Much: Stability, Growth & Emerging Markets

* Must-Read: : Here’s an Economic Agenda for Hillary Clinton

* Must-Read: : David Brooks Endorses Nepotism

Might Like to Be Aware of:

Rent-Seeking, Price-Taking Competition, Paul Romer, and the History of Economic Thought

Mark Thoma directs us to Paul Romer. And Paul Romer gets remarkably exercised about George Stigler’s long and successful war against the use of the theory of monopolistic competition in economics, with its consequence that even today we have “scientifically unacceptable” people who say:

We will never, as a matter of principle, consider a model in which there are ever any monopolies. We will dogmatically stick only to models of price-taking competition…

From my perspective it is not the contemporary implications of this train of thought for growth theory that are important–for as best I can tell there are people who write growth models where every market has price-taking competition but there is nobody outside who reads them–but rather the historical implications of this train of thought for industrial organization, antitrust, and the rise of the rent seeking sector in the American economy.

I eagerly want to read and hope to see more work in this area.

And there is something to be written about people who employ arguments based on ideological triggers. For them, certain arguments have force only when they lead to ideologically-convenient conclusions. We see this perhaps most strikingly in the Neoconservatives. Their core argument that government needs to be cautious, hesitant, and to focus on nudges rather than commands because (a) implementation is very hard, and general equilibrium effects are (b) often very large and (c) always very hard to predict. But, somehow, this argument applies only when the government is attempting to secure the natural rights of African-Americans, or women, or homosexuals. When the government is trying to stomp Commies or Arabs then, by contrast, they gravitate to arguments for an aggressive forward policy to secure “democracy”. Max Weber dealt with such people in his day: His line was: “the materialist interpretation of history is not a streetcar that one can get off of anywhere one likes.“

And, yes, all of what I call “Chicago Economics” does seem to be like that today–although very little of it was back in the 1930s…

Via Mark Thoma, Paul Romer:

…has to be judged a failure from a scientific perspective. In particular–and I apologize if this relies too much on the jargon of our field–monopolistic competition turns out to be just the tool for understanding…. (It also turns out to be the tool for understanding international trade, economic geography, and macroeconomics.) But there has been a series of models that are associated with the University of Chicago–from what some people call the freshwater camp in macroeconomics–that are continuing a fight that George Stigler started in the 1930s to keep monopolistic competition from being used in economics. It is hard to explain to an outsider why a whole group of economists have ended up on the wrong side of scientific progress, resisting the direction that all of modern economic theory is taking, but they are.

In the economics of ideas, we have to be willing to at least consider the possibility that someone could have some control over an idea, hence some monopoly power associated with ideas. This could come from patent or a copyright. It could also come from secrecy. Then we can ask if it is a good idea or a bad idea to have more intellectual property rights or more protection of ownership of ideas. We know that the answer here is mixed. Sometimes some amount of it can be good, but it can also be harmful if the property rights are too strong or are given to the wrong types of ideas. But if you don’t even allow for the possibility of ex post monopoly rents from the discovery of ideas, you can’t even ask the question.

So it is scientifically unacceptable to have people who say:

We will never, as a matter of principle, consider a model in which there are ever any monopolies. We will dogmatically stick only to models of price-taking competition.

I think this an untenable scientific stance. I don’t think that this critique is going to reignite interest in growth theory. But like I said, when it’s time for interest to come back, somebody have a new take on growth theory, and work in this area will start again. But in the meantime, we have to stop tolerating work that is scientifically unjustifiable.

Must-Read: Olivier Coibion et al.: How Do Firms Form Their Expectations? New Survey Evidence

: How Do Firms Form Their Expectations? New Survey Evidence: “We implement a new survey of firms’ macroeconomic beliefs in New Zealand…

…and document a number of novel stylized facts from this survey. Despite nearly twenty-five years under an inflation targeting regime, there is widespread dispersion in firms’ beliefs about both past and future macroeconomic conditions, especially inflation, with average beliefs about recent and past inflation being much higher than those of professional forecasters. Much of the dispersion in beliefs can be explained by firms’ incentives to collect and process information, i.e. rational inattention motives. Using experimental methods, we find that firms update their beliefs in a Bayesian manner when presented with new information about the economy. But few firms seem to think that inflation is important to their business decisions and therefore they tend to devote few resources to collecting and processing information about inflation.

Must-Read: Elizabeth Stoker Bruenig: David Brooks Endorses Nepotism

…a hearty endorsement in one of his increasingly deranged fireside chats, suggesting that since some ‘powerhouse families’ regularly produce successful members, ‘we should be grateful that in each field of endeavor there are certain families that are breeding grounds for achievement. … I bet you can trace ways your grandparents helped shape your career,’ Brooks advises, proving once again he knows zero people who are not rich….

Weekend reading

This is a weekly post we publish on Fridays with links to articles we think anyone interested in equitable growth should be reading. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week we can put them in context.

Links

Emily Badger looks at the new study on place and economic mobility and notes the important role of race. [wonkblog]

On that same study, Mikayla Bouchard points to the role of transportation and sprawl in determining mobility. [the upshot]

Andrew McAfee writes on Peter Thiel, Jean Tirole and monopolies. [ft]

Lydia DePillis reports on research describing how the economic background of politicians affects their voting. [wonkblog]

Ben Casselman busts the myth that millennials are constant job-hoppers and points out that even if they were that’d be a positive sign for wage growth. [fivethirtyeight]

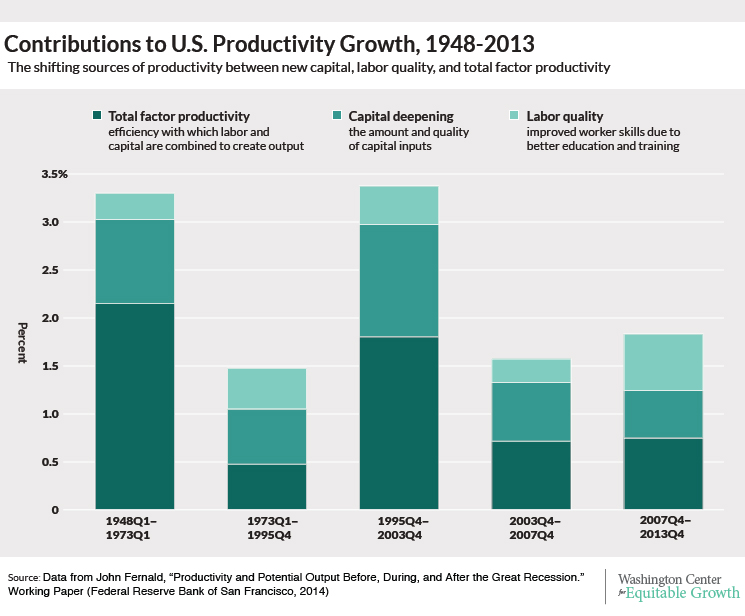

Friday figure

Figure from “The future of work in the second machine age is up to us,” by Marshall Steinbaum